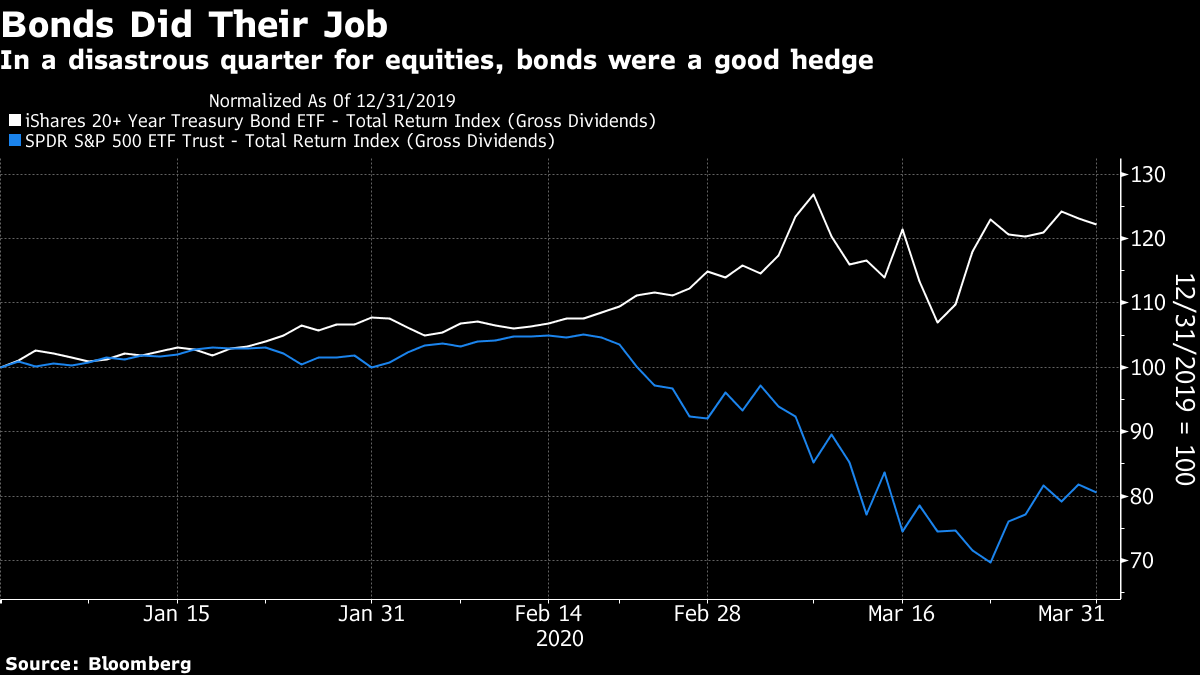

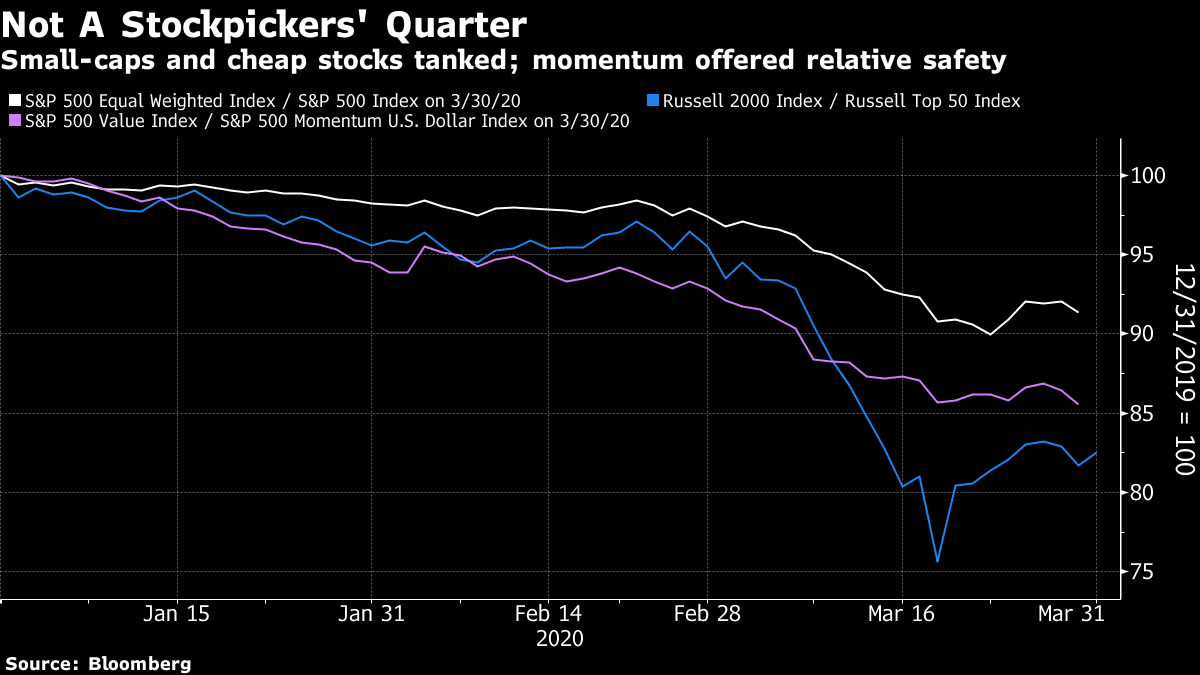

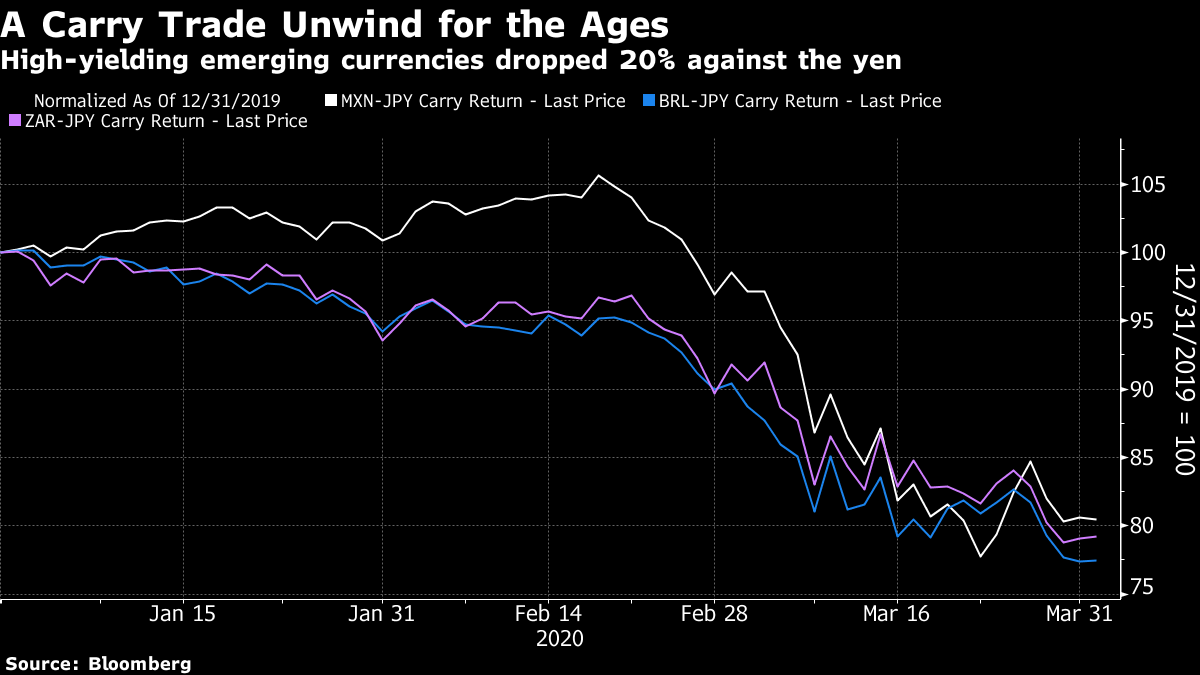

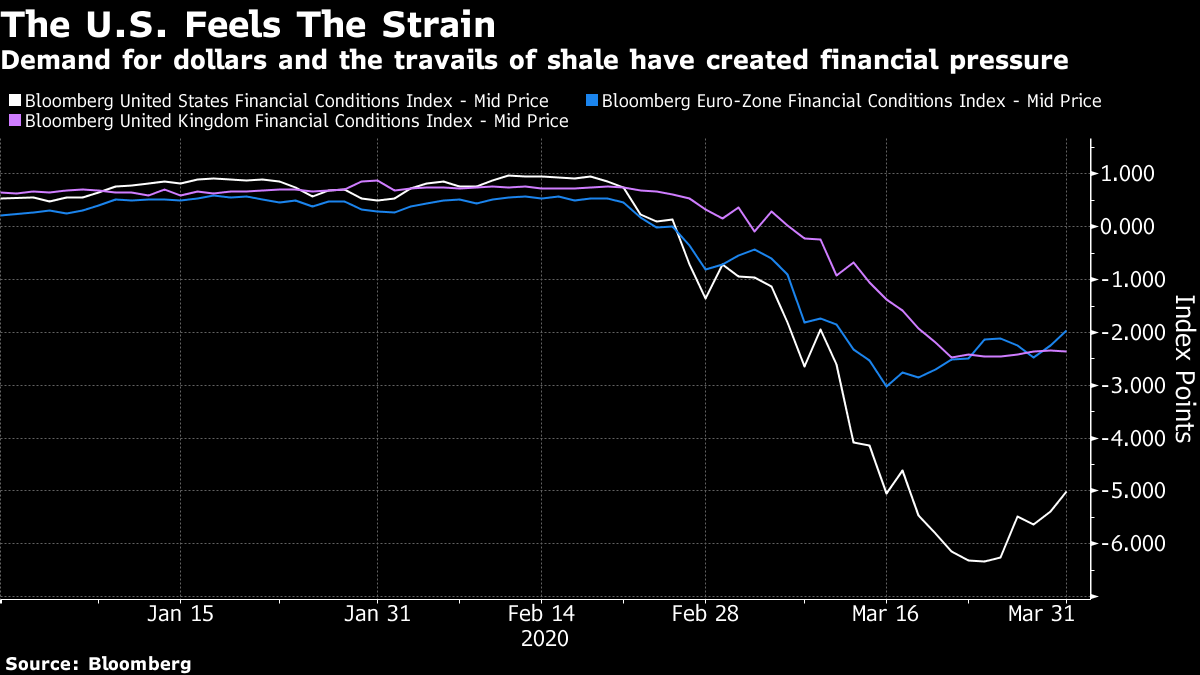

A Hung and Drawn Quarter The first three months of 2020 have been dreadful. This is mainly because the world has been afflicted by a pandemic that has forced many of us to live in social isolation. But also, a lot of people have lost money. As we survey the wreckage at the end of the quarter, however, we can see ways to have avoided the damage. The default position for long-term asset allocators is 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds. As this chart shows, long U.S. bonds did so well as everyone rushed for safety that the losses for a 60/40 fund were trivial, despite the 20% plunge for the S&P 500:  To be precise, a 60/40 fund would have lost only 2.8%, while a very conservative 50/50 allocation would have made 1.4%. If they rebalanced quarterly, they would both now be poised to buy a lot of stocks and sell bonds to do it. If it was a good quarter for conservative asset allocators to show their worth, however, it was an obscenely bad one for aggressive stock pickers. The way to minimize losses in the stock market over the last three months (other than sinking money into the handful of companies that should actually benefit from the pandemic) was to stick with big mega-cap stocks that were doing well already. These were the least risky options, that — crucially — were least reliant on leverage. As this chart shows, the underperformance for small companies, in a down market, has been cataclysmic, because of leverage. Value stocks have lost even more ground to momentum stocks. And the equal-weighted version of the S&P 500, in which each company begins with a 0.2% weighting regardless of size, has been clobbered by the cap-weighted version, meaning that the average stock lost badly to the index.  All of this may help put more active equity managers out of business, just in time for the moment when the market's extreme concentration into a handful of enormous multinational technology groups finally founders under the weight of its own contradictions. Within foreign exchange, the rush for dollars created a severe risk of an old-fashioned emerging markets crisis. That risk hasn't gone away. Anyone betting on the dollar at the outset of the year probably felt good; anyone trying a classic carry trade (borrowing in a low-yielding currency, parking in a high-yielding one, and pocketing the "carry") must be rather unhappy. Yen carry trades in the South African rand, Brazilian real and Mexican peso have all lost 20% or so in three months. For the Mexican peso, it was the worst quarter since the December 1994 devaluation that sparked the Tequila Crisis:  The rush for dollars has had its own impact on the U.S., which is feeling the strain of providing the world with safe assets. Bloomberg's financial conditions indexes, which combine a number of different pressure indicators, show that they have tightened far more in the U.S. than in the euro zone or the U.K. Again, a key to the problem is leverage: The U.S. corporate sector has binged on debt in an epic fashion over the last decade, and investors remain worried it will come unstuck. The good news is that conditions have eased slightly over the last week — the bad news is that this took record amounts of monetary stimulus, and the promise of a historic fiscal boost. If we get through the next quarter without a full-blown credit crisis in the U.S., many will be relieved and surprised (and richer, if they are holding corporate bonds).  Nothing transcends the importance of the fight by public health authorities against the pandemic. If we cannot at least see an end by the close of the next quarter, the situation will be grave indeed. In terms of the financial pressure points for the next quarter, U.S. corporations need to stave off concerns about their creditworthiness, as do emerging market governments. More or less everyone would benefit from a weaker dollar. Read All About It If you were taken by surprise by the pandemic, you weren't alone. Looking through newsletters for the last three months, I found this passage from Feb. 10: The global economy has grown for 43 quarters in a row, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the end of last week, Capital Economics Ltd. of London became the first group of economists (to my knowledge) to forecast that the coronavirus will break that streak. This seems reasonable; China's measures will depress activity, and take time to reverse. That creates issues for economies across Asia. It's only seven weeks since anyone suggested for the first time that this might mean a recession — and even then, the notion was that it would be primarily an Asian event, and over by the end of the year. When the facts change, we all need to be prepared to change our minds. And when we are most sure of the direction that markets are going, we might discover a turning point. As I pointed out earlier this week, it now looks like October 2018 was a pivotal moment, when stocks peaked relative to bonds and gold, and the oil price made a recent high. My thanks to Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts for providing these graphics, which juxtapose my own charts with headlines from the Wall Street Journal at the time the peak was made. (This isn't to throw shade at the WSJ — they were reflecting the contemporary sentiment, and I am glad with hindsight to have been between jobs at the time.)

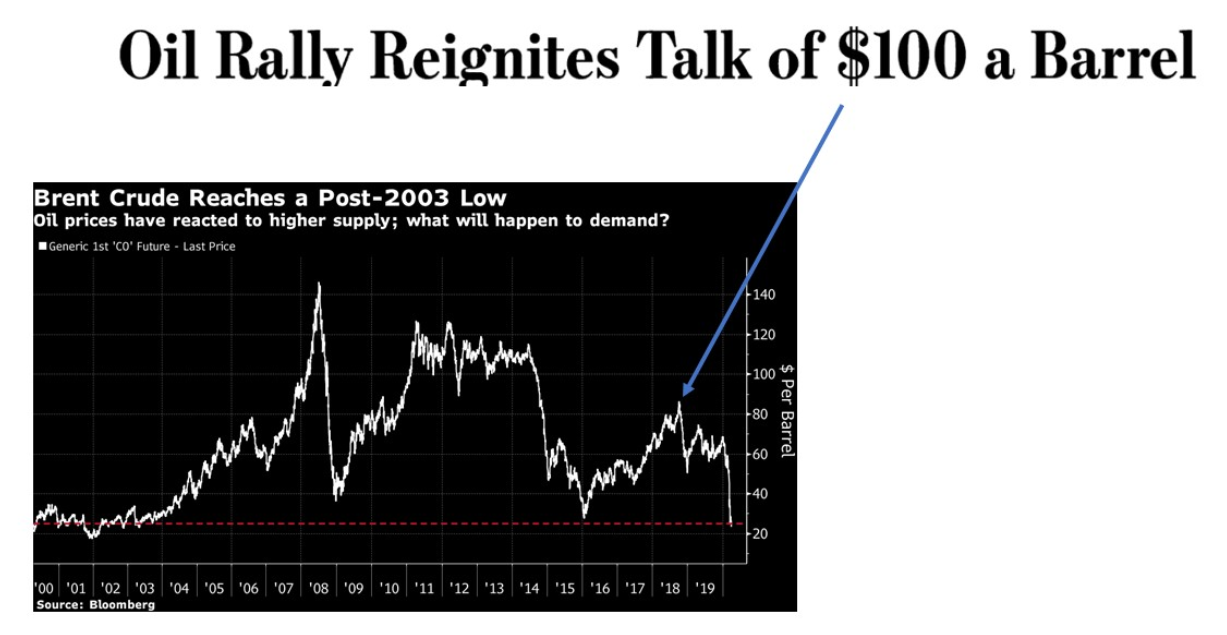

This is what the WSJ had to say about oil:

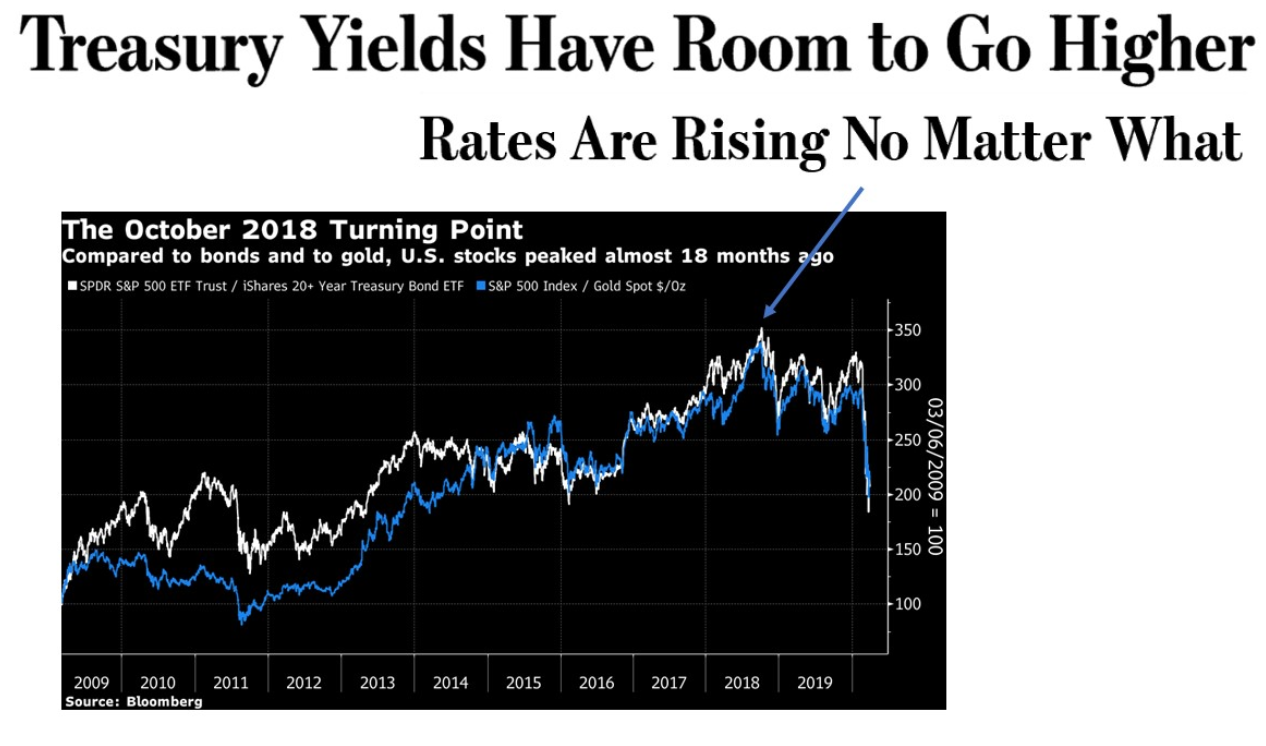

And this is what people felt about the alarming ascent of 10-year Treasury yields, which had exceeded 3%:  Remember October 2018 as the news gets darker. It is when there is certainty we are going in one direction that turnarounds happen. Survival Tips: Listmania Lists are great. Organizing your day in the current formless isolation often depends on drawing up a list and sticking to it. I always used to think that lists were the lowest form of journalistic life. They make for lazy clickbait. Sometimes, however, they can occupy time quite deliciously. Find something you care about, with lots of examples to choose from, where the ultimate ranking is almost entirely a matter of taste. Spend hours coming up with a top 50 or a top 100. Then share it with your friends and spend even more happy hours arguing about it. It has to be something you know and care about. As this newsletter has an international audience (and I'd like at this point to say hello to my one subscriber in Burkina Faso — I hope you're doing well in these troubled times), it is difficult to find a topic that everyone will find interesting, but I will make an attempt, with David Bowie. Like most British people of my generation, I am obsessively interested in him. Many others probably like something of his they've heard. So, The Guardian attempted the impossible task of ranking his top 50 songs, which you can find here. It includes a Spotify list so you can listen to clips. The real pleasure, however, isn't luxuriating in the music the Guardian chose, but picking holes in it. The 10 songs that were most criminally omitted include, as far as I am concerned: Ziggy Stardust (his theme song, which should arguably be number one, memorably covered by Bauhaus); Wild is the Wind, which many think is his masterpiece; Criminal World, a gem from Let's Dance; Five Years, the apocalyptic opening of the Ziggy Stardust album; We Are The Dead, one of several brilliant songs for an operatic version of Orwell's 1984; Speed of Life, the instrumental track which opens his wildly experimental Low album — much more exciting than the Guardian's number one from the same album, Sound and Vision; Under Pressure, recorded with Queen and an all-time classic (the Guardian included a song Bowie performed with his band Tin Machine, so why not this one?); Reflektor, in which he makes a guest appearance with latter-day proteges Arcade Fire — listen out for him about five minutes in; Lady Grinning Soul, the wonderfully operatic end to Aladdin Sane; and It's No Game, in which he opens the Scary Monsters album with a duet with a woman speaking in Japanese. I don't know if you enjoyed that list, but I certainly did. Lists can be a key to survival in social isolation. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment