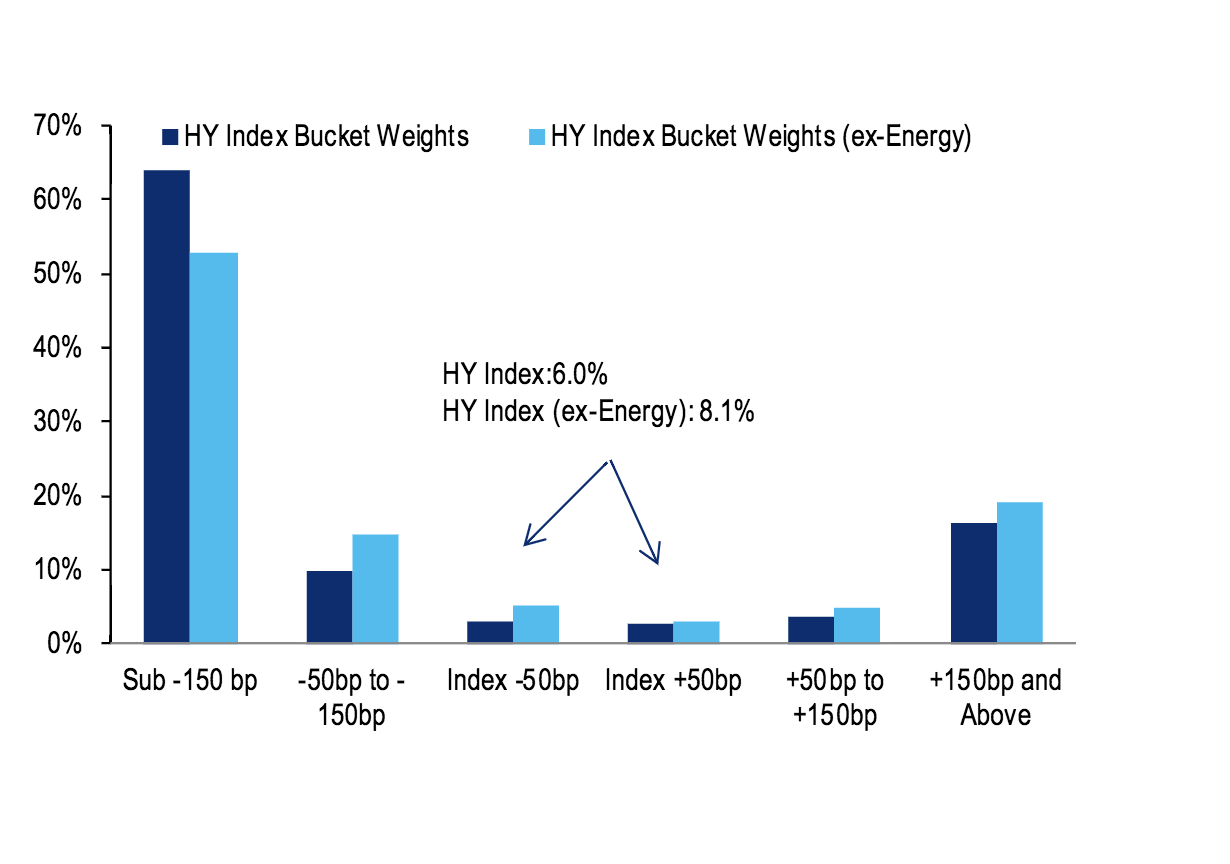

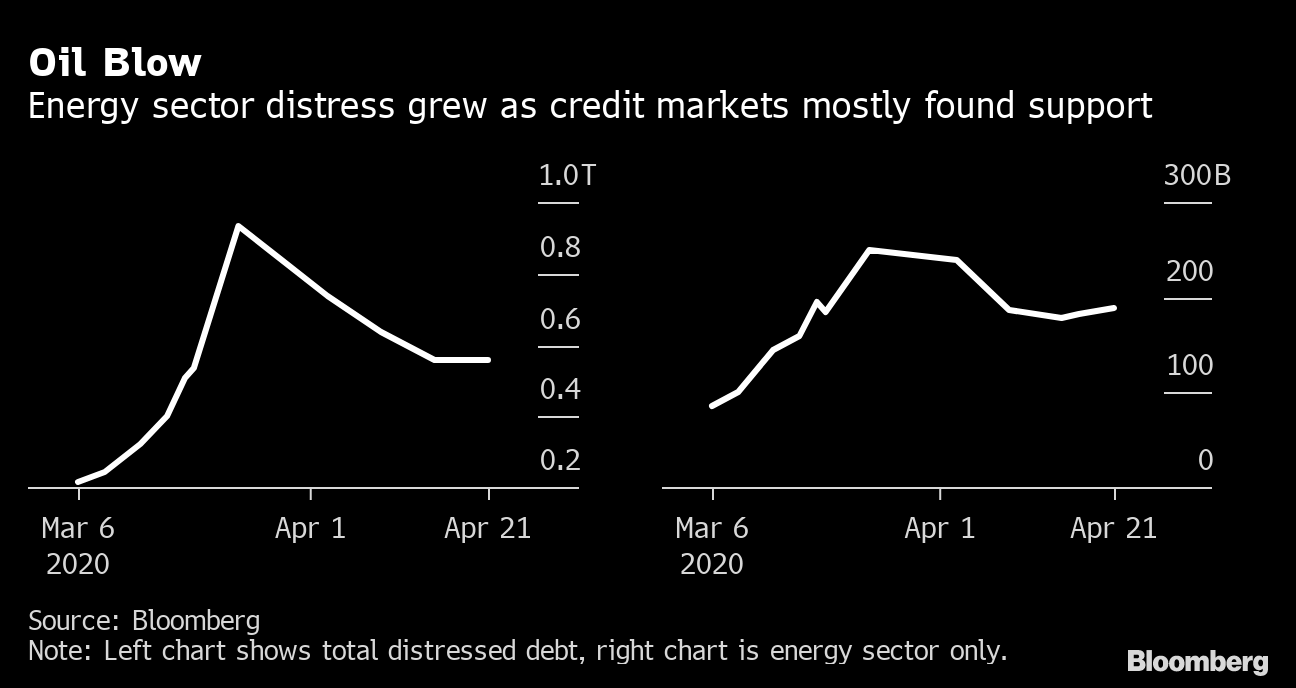

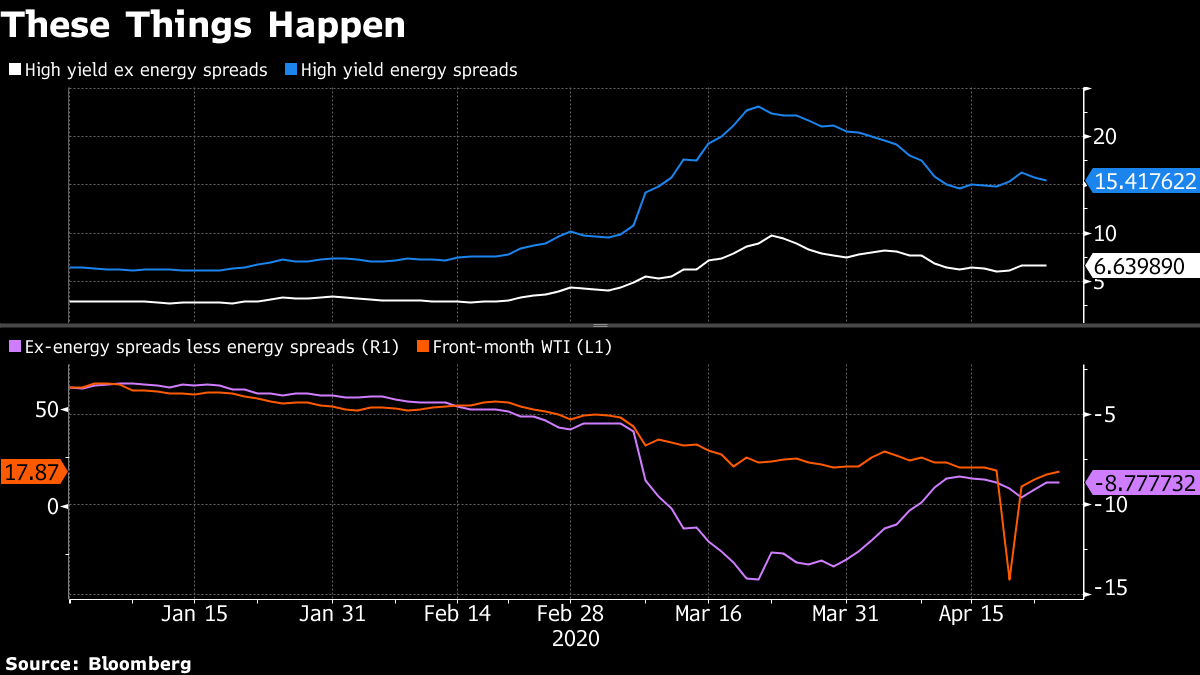

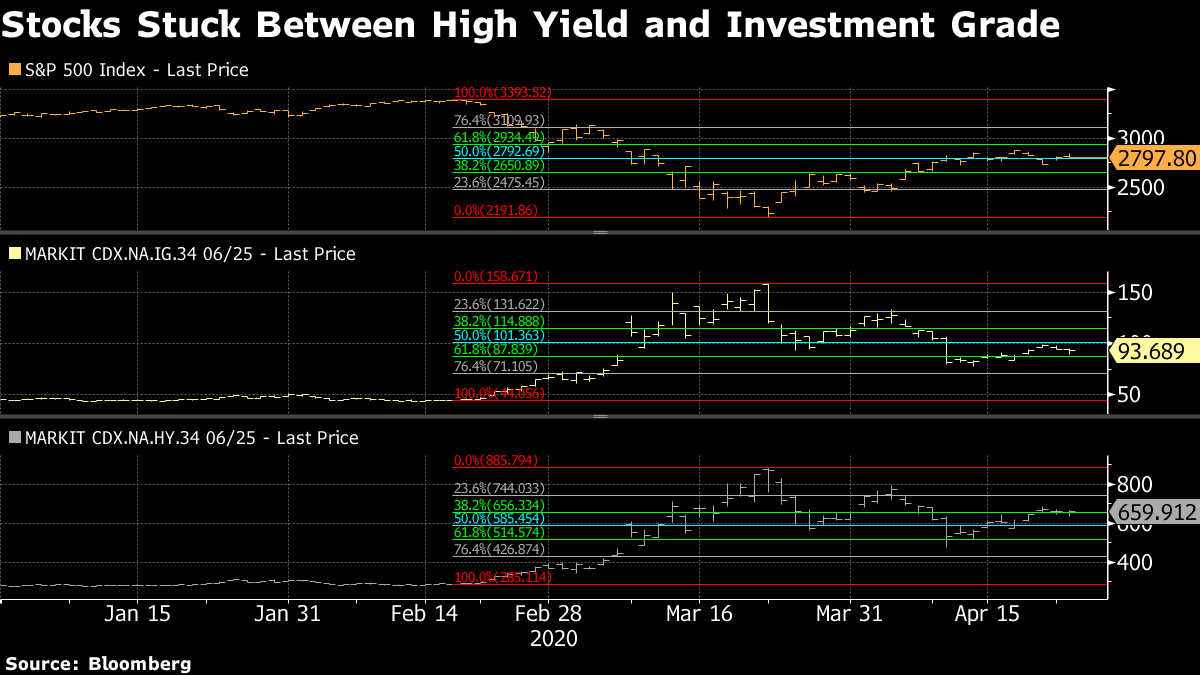

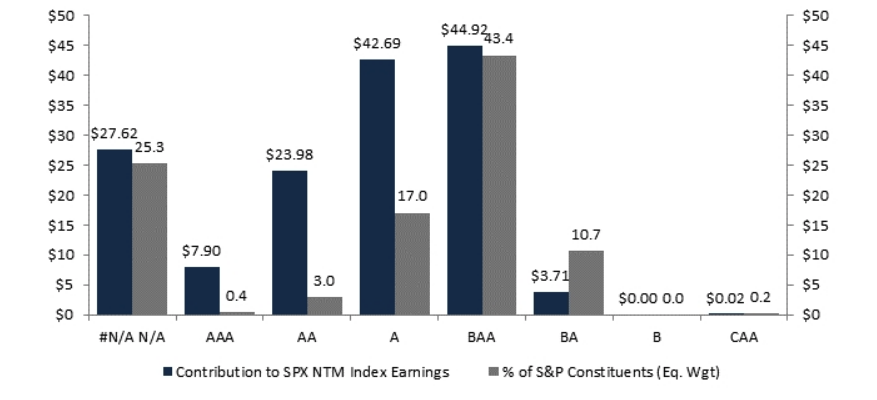

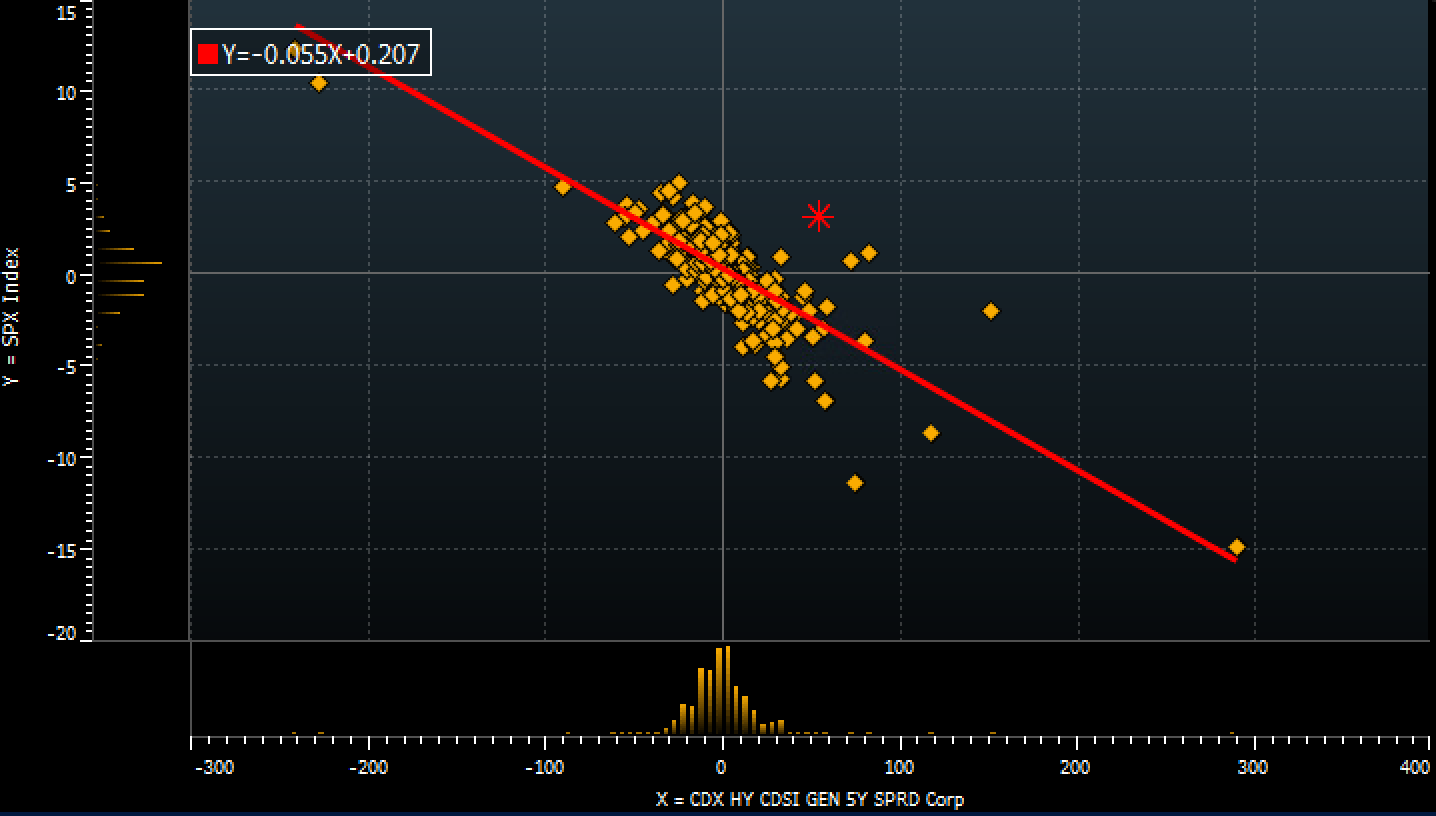

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's turning to zoological warfare tactics to get a handle on the corporate-debt market. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter From Bears and Bulls to Ducks and Horses One way to analyze U.S. credit these days is through the lens of a "gotcha" question that originated on internet forums and eventually ascended to interrogations of presidents and Supreme Court justices: Would you rather fight one horse-sized duck, or a hundred duck-sized horses? To overgeneralize, this is a way of asking if you'd rather tackle the big, scary, freakish problem or an agglomeration of smaller irritants. The Federal Reserve, known for its use of blunt tools, has slayed the horse-sized duck that is systemic credit risk with the proverbial sledgehammer: a backstop for investment grade and less-than-high-grade credits alike. Investors are still left to navigate a slew of industry-specific or micro, company-level risks. The dispersion in the junk market shows the degree to which this phenomenon has manifested itself. Michael Anderson at Citigroup Inc. puts it that the "high" in high yield comes primarily from extremely beaten-down groups that yield more than 150 basis points over the index yield -- with 40% of that universe in energy. "Market-wide levels may look attractive, but most of the spread comes from the bottom rungs," writes Anderson. "Less than 20% of the high-yield market yields within plus/minus 150bp of the overall index." Bargain-hunting is difficult, in other words. The high-yield market appears to have reached a point where it's difficult to buy individual credits or the asset class in its entirety, even when you cut out its most troublesome component.  Citigroup Citigroup An example of the extreme separation in high-yield debt: negative West Texas Intermediate oil futures saw the amount of distressed energy debt jump by $11 billion earlier this week.  And then Netflix's dollar-denominated bonds were issued at a 3.625% yield, among the lowest ever for U.S. junk bonds. Somehow, despite all this, the gap between ex-energy spreads and energy has actually narrowed this week. (Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin's consideration of a special lending facility for oil companies certainly won't hurt.)  Such is the conundrum facing credit investors: although the dispersion among individual credits is immense, analysts aren't pounding the table on buying opportunities. And to make matters more exasperating, energy and ex-energy will tend to trend together. Bespoke Investment Group pointed to the correlation between HYG, the broad high-yield ETF, and HYXE, which excludes energy, as evidence of the practical difficulties in treating the asset class as a cohesive whole even when its problem child is excluded.  "The fact that these two ETFs track each other so closely is evidence of why the weakness in oil markets can't be shrugged off by high-yield bond markets, equity markets, or the broader economy itself," the analysts write. "Leverage, supply chains, and other factors are all at play." Stuck in the Middle Two weeks ago, stocks had retraced a much smaller portion of their declines than investment grade and high yield had retraced their spread widening -- which could have signaled that credit investors were focused on Fed policy addressing systemic risks while their equity counterparts were still chastened by a troubled earnings picture.  The gap between investment grade and high yield also reinforces the importance of size and quality to investors. The price actions are fitting, in a way. On the one hand, stocks do fall below all of credit in the capital structure. On the other, this chart from Evercore ISI's Dennis DeBusschere shows a plurality of S&P 500 constituents are BBB rated -- the last rung on the investment grade rating (with the potential to become fallen angels should the magnitude or severity of the crisis exceed current expectations).  Evercore ISI Evercore ISI Of course, compositional issues between stock and credit indexes aren't necessarily apples-to-apples comparisons. But the recent price action in stocks could be described as catching up (well, down) with credit, especially in high-yield. Last week was the first time the S&P 500 Index gained at least 3% while 5-year junk credit default swap spreads rose at least 50 basis points since at least August 2012. Investment grade credit default swaps spreads also widened, albeit marginally.  Bloomberg Bloomberg |

Post a Comment