A Passover Night Unlike Any Other Wednesday marks the first night of Passover, the festival at which Jews the world over gather to commemorate the exodus from Egypt by eating a highly symbolic meal, known as a Seder. Jesus's Last Supper, at which he told his followers that the wine was his blood and the unleavened bread (Matzoh in Hebrew) his body, was a Seder. It is one of the most profound and influential rites in Western civilization. It starts with the youngest person present asking four questions (in Hebrew, in a beautiful lilting tune) about why the Passover night will be different from all other nights. The idea is to encourage the younger generation to question an ancient tradition, and force others present to explain why the story of Exodus is so important. Since 2008, I've made a habit of asking four financial questions each Passover. I find it's a great way to home in on the anomalies in the markets and try to understand them. And some, such as Bloomberg Opinion colleague Aaron Brown, have even started copying it), which is the sincerest form of flattery. This year's Passover threatens to be different from all others, because extended families won't be able to gather together. Instead, many will attempt to hold virtual Seders using different kinds of video-conferencing. It will also be different because the plagues at the center of the narrative seem much more real now. In normal times they lead to questions about our abstract notion of a benevolent God; this year the questions are much more immediate. So with the knowledge that the Seder carries extra baggage this year, here are 2020's four financial questions for Passover:

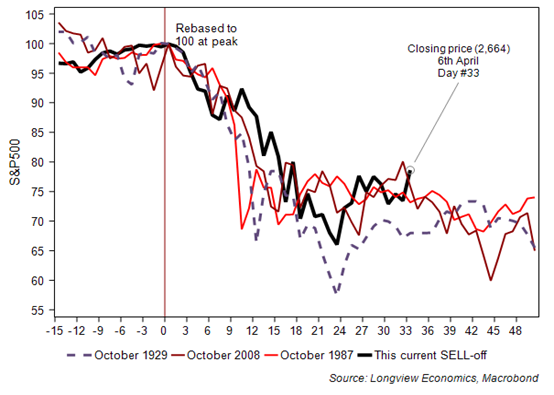

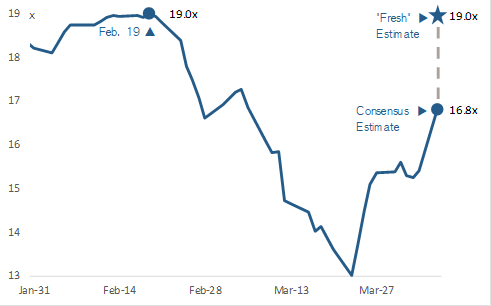

Why is the U.S. stock market already back in a bull market, when after all previous bear markets it took much longer to hit bottom? First, let us get some definitions right. It is common to refer to any peak-to-trough fall of 20% as a "bear market." I don't know where this definition came from, and it isn't terribly useful. But even if we accept it, it doesn't follow that a 20% gain from the bottom, briefly made for the S&P 500, is a new bull market. It might be, but we can only tell in hindsight. If stocks go on to set a new high without revisiting their low, we might come to recognize that we are already in a bull market. Why doubt this? After big falls, big rebounds are to be expected. This chart compares the S&P 500 since its pre-Covid peak on Feb. 19 with its performance after Sept. 12, 2008, the last trading day before Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy:  We are following that road map very closely — and back in 2008 there would be two new downdrafts, and two new lows, before the U.S. stock market bottomed for good in March 2009. This isn't peculiar to Lehman. The following chart from Chris Watling of Longview Economics in London throws in the market's behavior from the Great Crash of October 1929 and Black Monday in October 1987. The patterns are startlingly similar:  None of this proves that history will repeat again. But it gives good reason to doubt that the bottom is in. Another reason for caution comes from valuation. Analysts have been understandably slow to revise their forecasts for first quarter earnings, which will start to appear next week. Research by Jonathan Golub, equity strategist at Credit Suisse Group AG in New York, shows that if we use only estimates that have been revised in the last week, then prospective earnings multiples are already back to their Feb. 19 peak. Markets have effectively done nothing more than price in one set of bad earnings results, and returned to what already in February looked like a very expensive valuation:  Tackling this another way, look at trailing price-sales multiples. As of February, the S&P 500 was even more expensive than it had been at the top of the dot-com bubble in 2000. This reflected the belief that companies will continue to command higher profit margins — and thus justify a higher multiple of sales.  One of the more popular predictions at present is that profit margins will be a permanent casualty of Covid-19. Companies are under pressure to keep more cash on hand to guard against emergencies, which means fewer stock buybacks and lower profits. Workers' bargaining power may also be higher, and government regulation tighter. So a return of price-sales multiples to where they were would look hard to sustain. The answer, then, appears to be that U.S. stocks aren't in fact in another bull market. They have only been able to recover as much as they have because the extent of the long-term virus damage is still unclear and therefore unpriced. If lockdowns need to drag on and then be repeated two or three times, as many public health officials now suggest, the stock market will have to fall further.

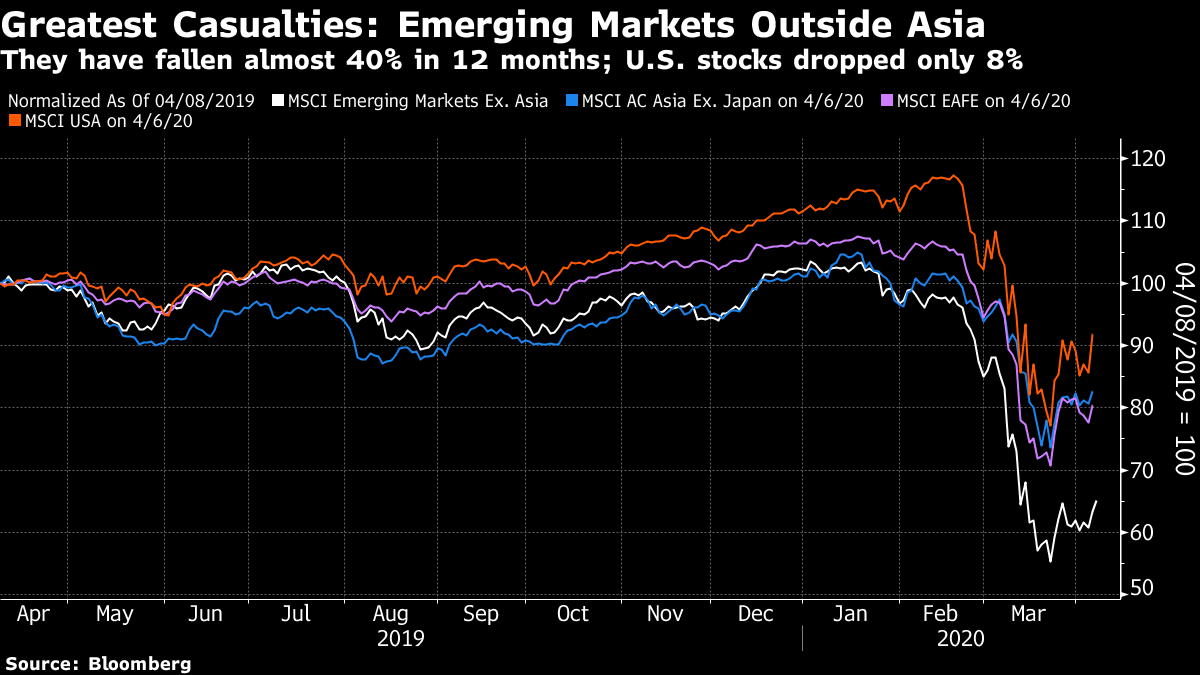

Why have emerging markets outside China been priced down so badly when all other countries have suffered more from the coronavirus?

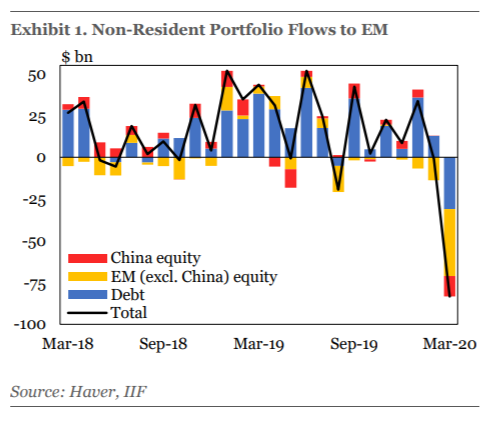

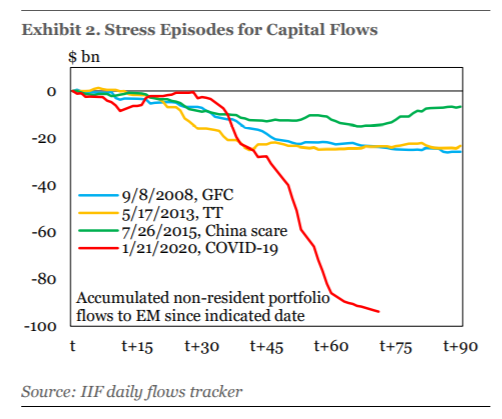

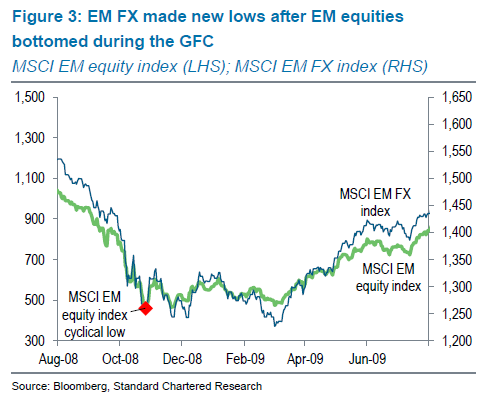

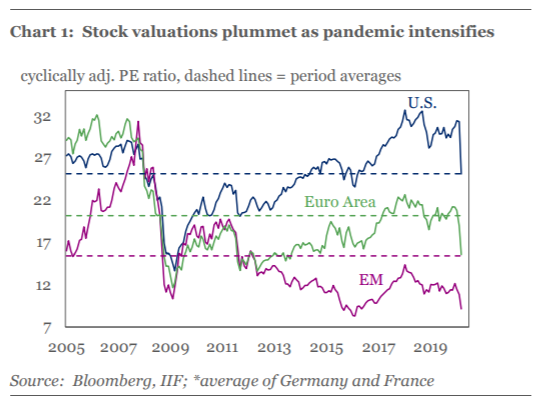

The extent of the sell-off for Latin America, eastern Europe and Africa is startling. As the MSCI indexes show, emerging markets outside Asia have come drastically detached from China, having previously traded on the assumptions that their interests were aligned. This is all the more remarkable because the virus is currently most deadly in western Europe and northern America. The regions least scathed until now are the ones to have suffered the greatest equity declines:  Figures from the Institute of International Finance show that emerging markets are suddenly much out of favor with international investors. Equities outside China have taken the brunt of the exodus:  It is usual for emerging market stocks to be dropped like a hot potato at the first sign of an international financial crisis, but this time the reaction is exceptional. The following IIF chart compares flows out of emerging markets with those after Lehman in 2008, the taper tantrum in 2013, and the scare over a disorderly Chinese devaluation in 2015:  Worse still, sell-offs for emerging stocks tend to bring currency declines in their wake. This chart from Standard Chartered Plc shows that emerging currencies kept falling after equities had made a bottom in 2009:  That has alarming implications for emerging economies, because many still have plenty of dollar-denominated debt, which would become far harder to service. The Federal Reserve's attempts to alleviate a dollar shortage in the last few weeks have addressed that fear — but any further falls for emerging currencies would be hard to handle. Meanwhile, if we use cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiples, emerging markets have moved from very cheap to unbelievably cheap. This is another chart from the IIF:  What is going on? A global slowdown stands to hurt the weakest economies worst. That means Latin America and Africa. But most importantly there is the issue of Covid-19. Countries with poor health systems, concentrated populations, and an economy where most don't have the option to work from home, naturally stand to suffer far more. A human catastrophe is possible. Some leaders of the emerging world, notably Jair Bolsonaro, appear alarmingly relaxed about this threat. If catastrophe can be averted, then emerging markets will look like good value indeed. Until we can be sure that Covid has done its worst, however, it will be hard for emerging markets outside Asia to recover.

How can companies possibly be issuing so much credit, and investors buying it, when they have too much leverage already?

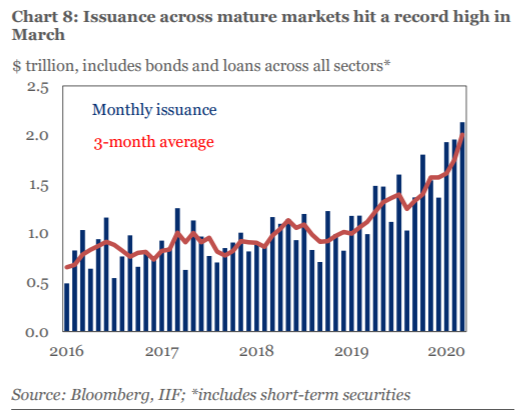

Corporate credit issuance is running at record levels. If we look at monthly figures (excluding the week or so when the market froze), we see an uninterrupted upward trend:  The most important factor supporting issuance is, of course, the Fed. If the U.S. central bank has announced that it will buy corporate bonds if necessary, then why not issue some, and why not buy them? As many companies entered the lockdown period with inadequate cash, they were all the happier to sell bonds. And with Treasury yields dropping to record levels, this could happen at attractive rates, even though the spreads over risk-free rates remained elevated. Even though the big central banks have gone "all in," it is startling to see how wide spreads remain. Investment-grade, emerging market and U.S. high-yield spreads have narrowed in the last few days, but remain wide:  Companies are going to be supported through the months of lockdown. A cascading default crisis won't be allowed to happen. That makes the world safe for creditors and debtors, which is what central banks wanted. The corollary is that debt takes precedence over equity. In straitened circumstances, it looks more appealing to be higher in the capital structure, with a superior claim on a company's cash flows. And of course, the longer the lockdowns have to go on, the greater the strain on corporate finances, and on central banks attempting to plug the gap in their revenues. Why are markets priced for enduring deflation when central banks are in the process of printing more money than at any other time? Markets are obviously braced for declining or stagnating prices. The recent fall in oil, driven by the breakdown in OPEC discipline, has only accentuated a long-running trend. Other commodities have fallen in line with oil. This implies a sluggish economy and deflation:  As for inflation break-evens generated by the bond market, they have rebounded in the last few days, but remain at levels unseen since 2008. Japanese 10-year break-evens are actually negative, and for the U.S. they are only just above the 1% lower limit of the Fed's target inflation range:  The rationale for all of this is clear. The virus has prodded governments to shut down their economies. That will mean slow activity. Meanwhile central banks may be active, and governments may promise enormous fiscal stimuli, but they are only filling a gap left by the lost revenues of the lockdown. That explains the confidence of the bet on deflation. Is it safe? Past epidemics have strengthened the position of labor, leading to higher real wages. As supply chains creak back into action, we can expect plenty of shortages that lead to higher inflation. The market at present is making a reasonable assumption about the net impact of the virus, but it could well turn out to be wrong. Virtually nobody is positioned for a return of inflation, so that could yet be the worst pain trade around — a lasting financial symptom of Covid-19.

If there is a thread running between these questions, it is that they can only finally be answered when we know the eventual human toll of the virus. For now, scarcely anything matters beyond limiting that.

A safe and happy Passover to all who celebrate it. An equally safe and happy Easter for those who celebrate that instead. And good wishes to everyone who celebrates something different, or nothing at all. After all, we now know that we are all in this together. (And get well soon, Boris.) Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment