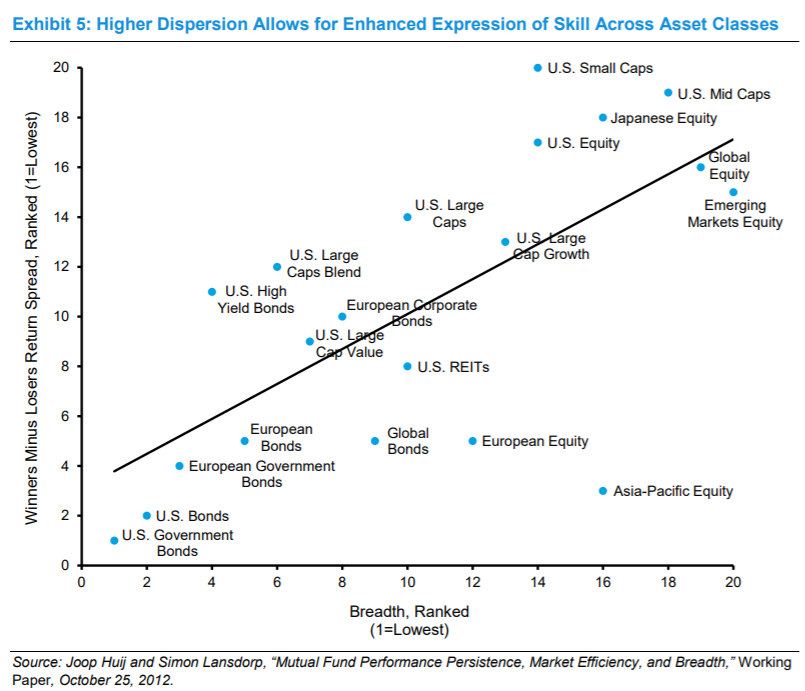

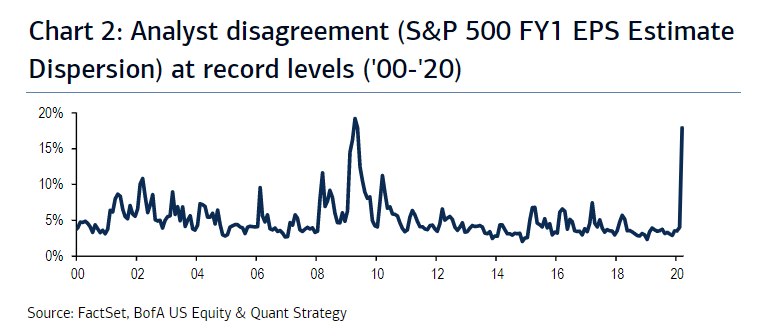

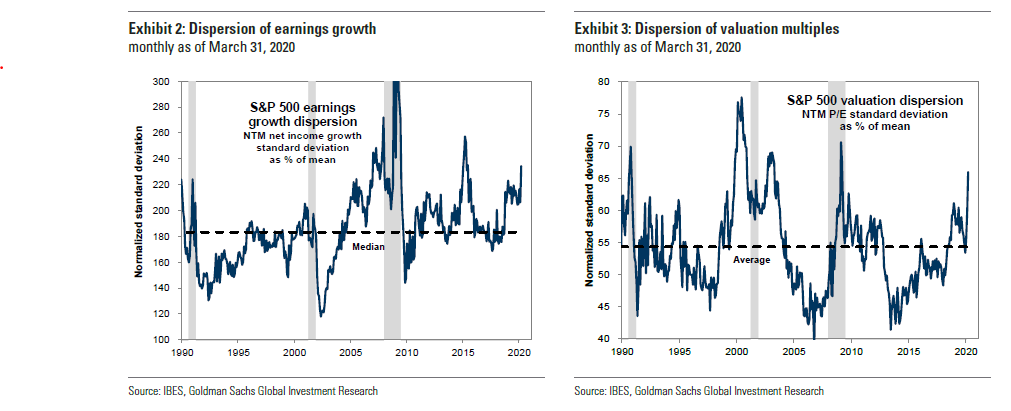

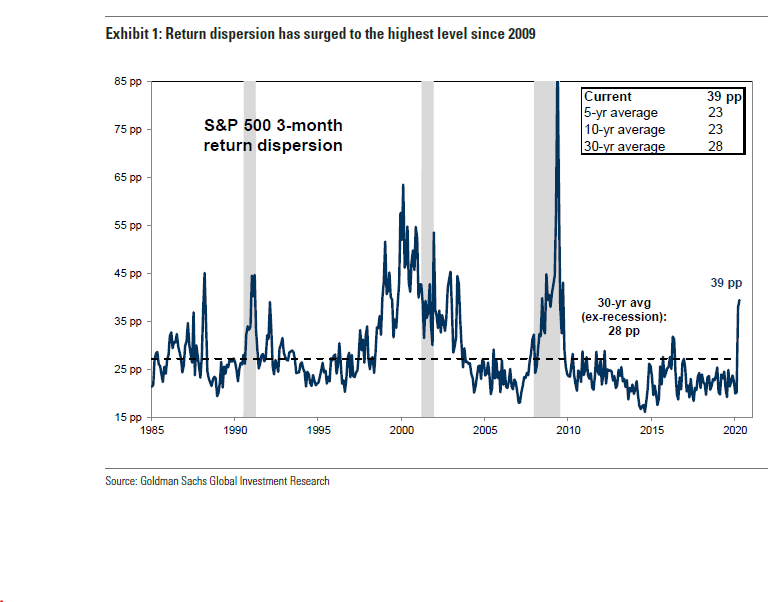

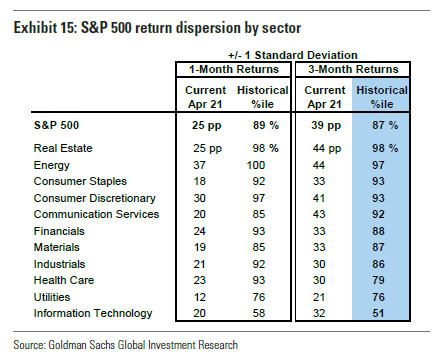

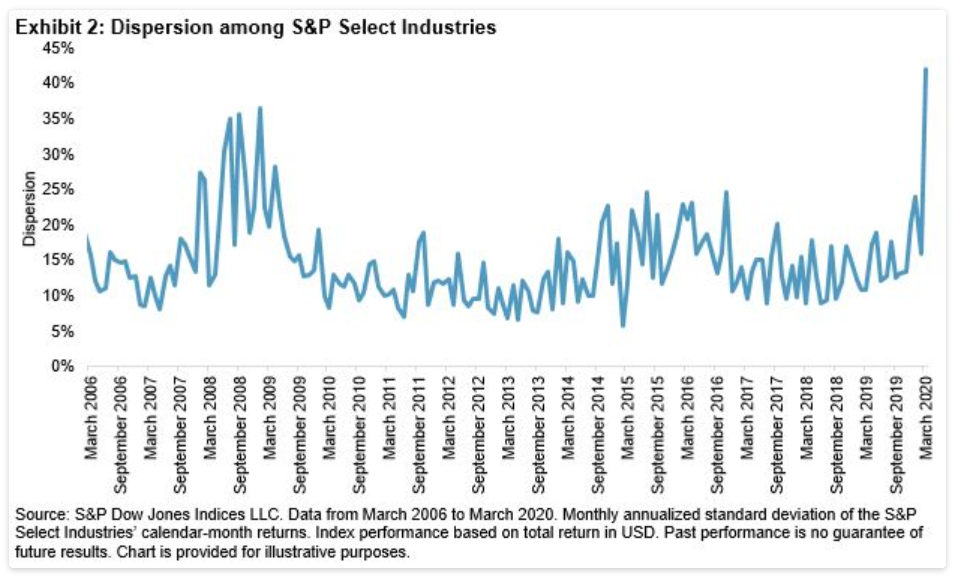

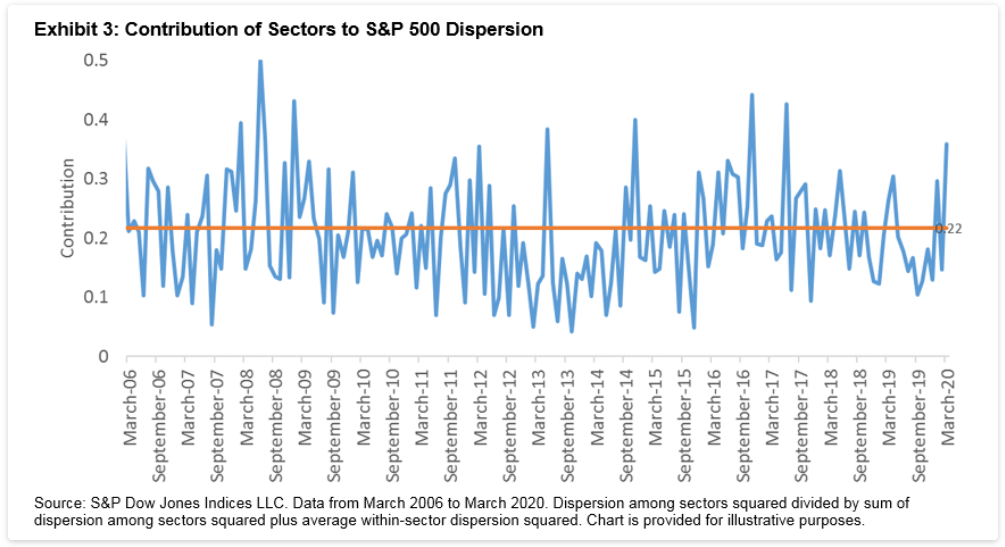

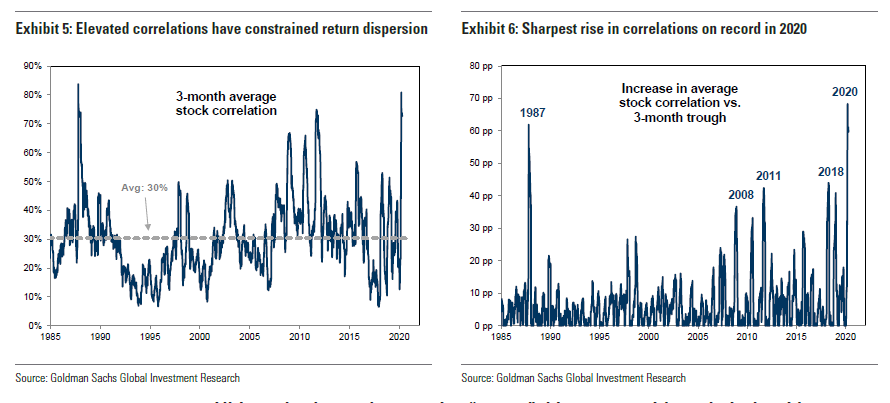

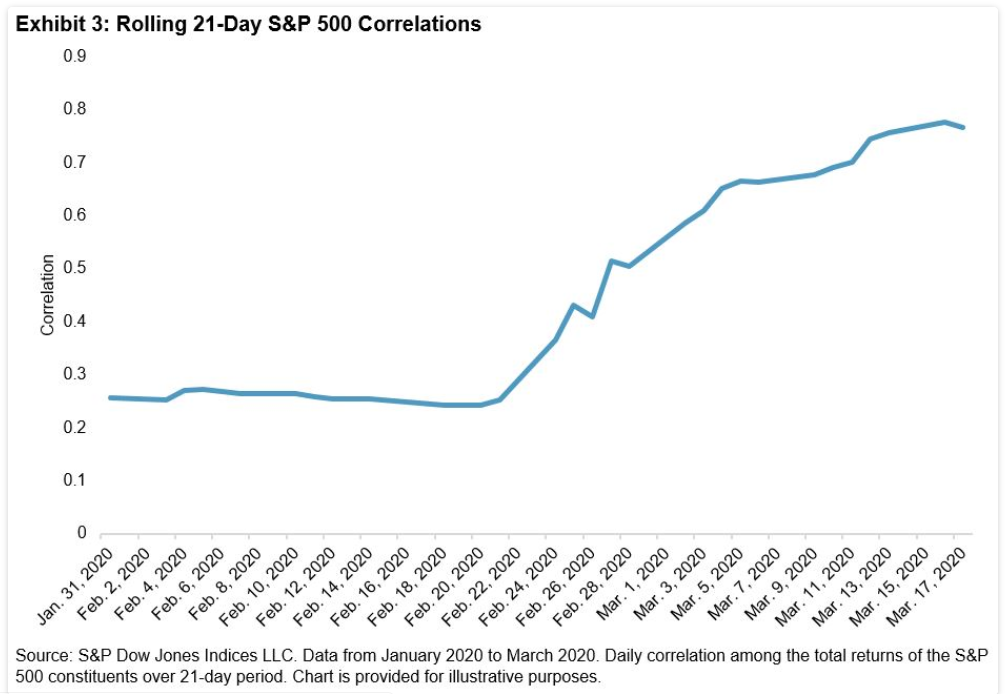

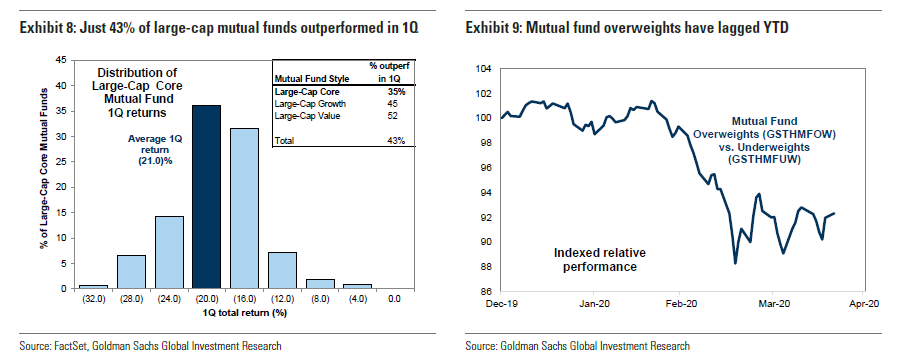

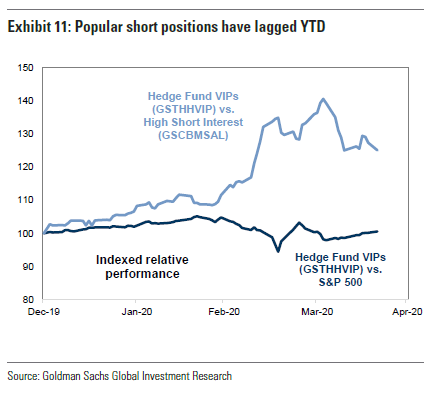

Opportunity Knocks, Covid-19 Edition For many years, active managers have awaited the return of a "stock picker's market." This is one where the skill of investors can show itself to greater advantage. It may just have arrived. Now, all stock pickers have to do is pick the right stocks. Assuming we believe that there is such a thing as skill in this process, then a stock pickers' market is one where there is the widest dispersion of returns, so that superior selection will make the most difference. The veteran investment theorist Michael Mauboussin, now at Morgan Stanley, goes into deep detail about this in a paper published this month. As he shows, the greatest opportunities are in smaller companies and in emerging markets, while it is hardest to make skill count in the world of bonds. U.S. large caps are also a harder environment, arguably made more difficult in the last decade by the rise of passive investment:  We need to be careful about this argument. Higher dispersion gives you a greater ability to show off your virtuosity, but it also gives you a greater opportunity to make a fool of yourself, as Anu Ganti, director of index strategy and S&P Dow Jones Indices, argues. As she puts it, this argument is correct at one level. "We are in precisely the environment in which active portfolio managers have the most potential to add value, since relative returns are easier to achieve when absolute returns are poor." In other words, "the value of stock-selection skill rises when dispersion is high: a larger gap between winners and losers means that active managers have a better chance of displaying their stock-selection abilities." This should therefore be a great time for active managers. As the quantitative team at Bank of America Corp. shows, the dispersion of earnings estimates entering the current reporting season was at a record high, topping even the confusion around the financial crisis a decade ago:  Goldman Sachs Group Inc. further shows that both earnings growth and multiples entered this results season with unusually high levels of dispersion:  So it shouldn't be a surprise that dispersion in three-month returns is indeed running at its highest since the last crisis, although not yet at anything like the levels seen at the last big market breaks in 2000 and 2008. That is likely to change as the drama advances:  There is also elevated dispersion within industrial sectors, with the significant exception of information technology:  It is as well to be careful about this. The disturbance in markets so far has been driven from the top down by an almighty macro shock. Dispersion within sectors is high — but dispersion between sectors is at a record, according to S&P:  S&P also shows that the difference between sectors is itself contributing more than usual to total dispersion:  Putting this differently, picking the best-performing cruise line might be a skillful thing to have done, but it isn't going to make your clients very happy. The point of this market disruption has been to get the macro direction right. That leads to another factor in favor of stock pickers — correlations between shares are higher than usual. This might seem to be bad for active investors, but remember their need to show a benefit for having a small concentrated portfolio, rather than a big diversified fund that tracks an index. To quote Ganti of S&P: active managers should also prefer high correlations to low correlations. This is because active portfolios are typically more volatile than their index benchmarks; active managers forgo a diversification benefit. When correlations are high, the benefit of diversification falls, as does the benefit forgone, making active management easier to justify. If ever there was a time to forsake diversification, it is now, as these charts from Goldman show:  Correlations increased sharply as the severity of the coronavirus crisis became apparent in late February and early March, as this S&P chart shows:  They should gradually reduce when the crisis eases. So the challenge is clear. Active managers had to spot the sectors that would do best out of the Covid outbreak as it was starting, and hold on tight. Those that have emerged victorious so far generally did so by betting big on the biggest internet stocks. That's a dangerous strategy because they need to be very heavily exposed to stocks that already have a big place in the index. Overall, so far, mutual funds haven't risen to the challenge:  Generally, the stocks that mutual funds overweighted have lagged behind the index this year. Success has gone only to those who took a big bet on momentum and trusted to the FAANG stocks (Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Netflix Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc.). Hedge funds appear to have fared better, according to Goldman. But this points to another problem. It has been difficult to make money on the "long" side, betting on winners. Popular stocks with hedge funds have barely done any better than the index. But they have the crucial advantage of being able to bet against a company by selling it short. And the gap between their favorite longs and shorts suggests this is paying off for them:  Active management has had a dreadful decade since the last crisis. So far, in aggregate, it has failed to spot the relative winners from the turmoil of the last few weeks. The fortunes of many large investment houses now hang on identifying the winners before the world emerges from the Covid crisis. Survival Tips Don't inject yourself with disinfectant. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment