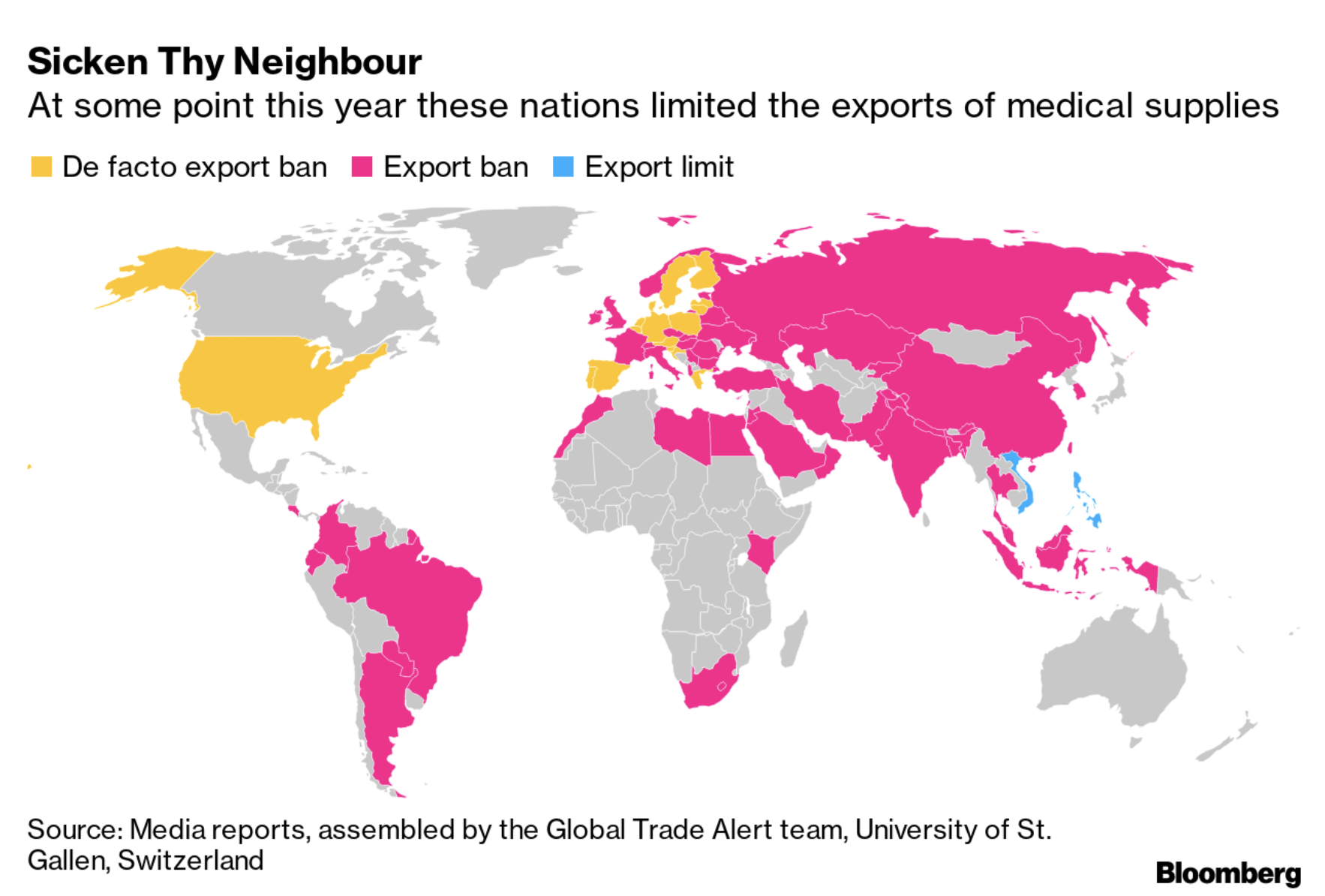

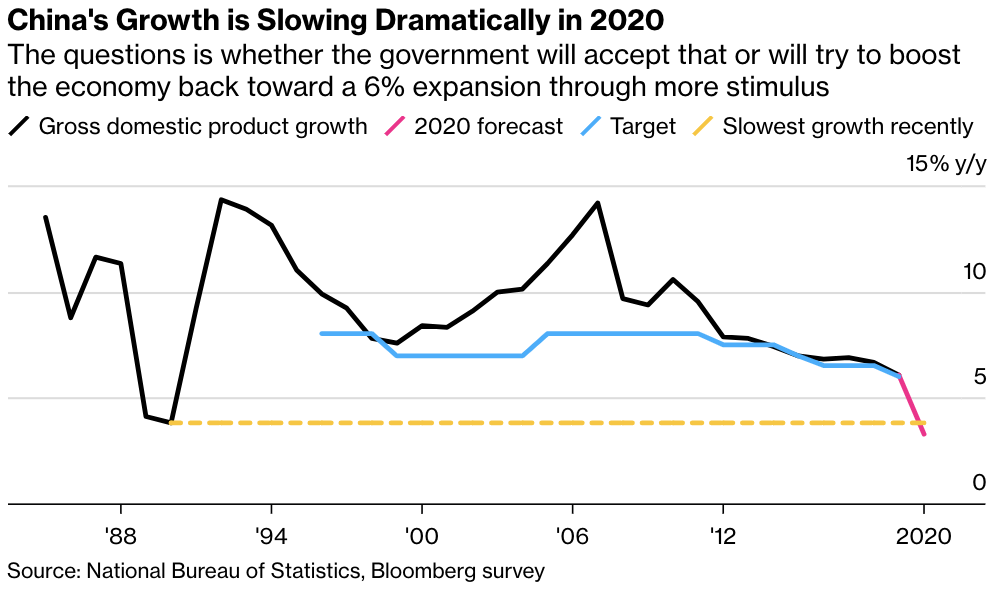

| Buying a cappuccino in Beijing these days involves a temperature check, leaving the barista your contact info and using your mobile phone's location tracking to prove you've not been to any "hotspots" recently. But at least the coffee shops are open. After fighting the coronavirus for three months, life across China is recovering. It's happening even in Wuhan, where the virus that's now killed about 90,000 people around the world first emerged. Authorities this week began rolling back a city-wide quarantine there and allowing thousands to leave for the first time since late January. That's not to say China is back to normal. Far from it. Schools remain closed. Sporting events, business conferences and other large gatherings have yet to resume. Foreign nationals are still barred from entering the country. It is, as Bloomberg's John Authers aptly called it recently, the new abnormal. And it looks like it will be with us for a while. This new state of being has had obvious implications for how people interact: The handshake has largely been abandoned in Beijing, for example. More consequential is how it may affect the relationships between countries. We've had a sense of that already. Universities around the world are having to confront their growing dependence on international students and the possibility that there won't be as many in the future. The entire travel industry, from airlines to hotels, is facing a very uncertain outlook. And then there's the global supply chain.  As infections have surged, many countries have faced shortages of masks, ventilators and other medical supplies. That's led to heated rhetorical skirmishes and export bans, all of which have added to the argument that countries shouldn't depend on others for crucial supplies. Some countries are already taking steps to lure back manufacturing. Tokyo this week set aside $2 billion to help subsidize Japanese companies that want to move their manufacturing from China back home. If this is the start of a trend, the future could look very different. Economic Growth For many years, gross domestic product held a special preeminence in China. During the early 2000s, double-digital GDP growth became shorthand for China's success. Premiers announced annual targets during the pomp and circumstance of the National People's Congress. Local officials were judged on it. But more recently a growing number of economists have begun to argue that policy making would be improved if it focused less on GDP and more on jobs, debt and financial risk. That argument could get a boost next Friday when China is expected to report the country's first contraction on record. What would have been unthinkable before the coronavirus will be far more acceptable, given the measures that pummelled the economy were the same ones that got the outbreak under control. Breaking the taboo of negative GDP could also make the idea of moving that dataset to the back burner a little more palatable.  Accounting Issues April has been a rough month for China Inc. Days after high-profile Starbucks challenger Luckin Coffee announced that its chief operating officer and some underlings may have fabricated billions of yuan of transactions, TAL Education Group said a routine internal audit found an employee had inflated sales by forging contracts. Corporate governance and a lack transparency are not new problems for China's companies, which is why these recent revelations stand to have such far-reaching reverberations. What could make things even worse, of course, is the disclosure of further malfeasance. Given the state of the economy and the prospects for a slow and arduous recovery ahead, that's a real possibility. Global Image China's best-known business man, meanwhile, has been doing pretty well. Jack Ma's global profile is noticeably on the upswing as China's richest man has mustered his resources to help supply masks, ventilators and other medical equipment to jurisdictions around the world. His efforts have been praised by the likes of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and U.S. President Donald Trump. They should also be making him popular in Beijing, which has been busily burnishing China's image as a responsible global citizen and fighting off assertions that it's to blame for the pandemic. While donations from the Chinese government can be met with suspicion, those from Ma have faced less stigma. What they have in common though is that they all generate goodwill for China.  Jack Ma Photographer: Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg What We're Reading And finally, a few other things that got our attention: For the latest virus news, sign up for our daily podcast and newsletter. |

Post a Comment