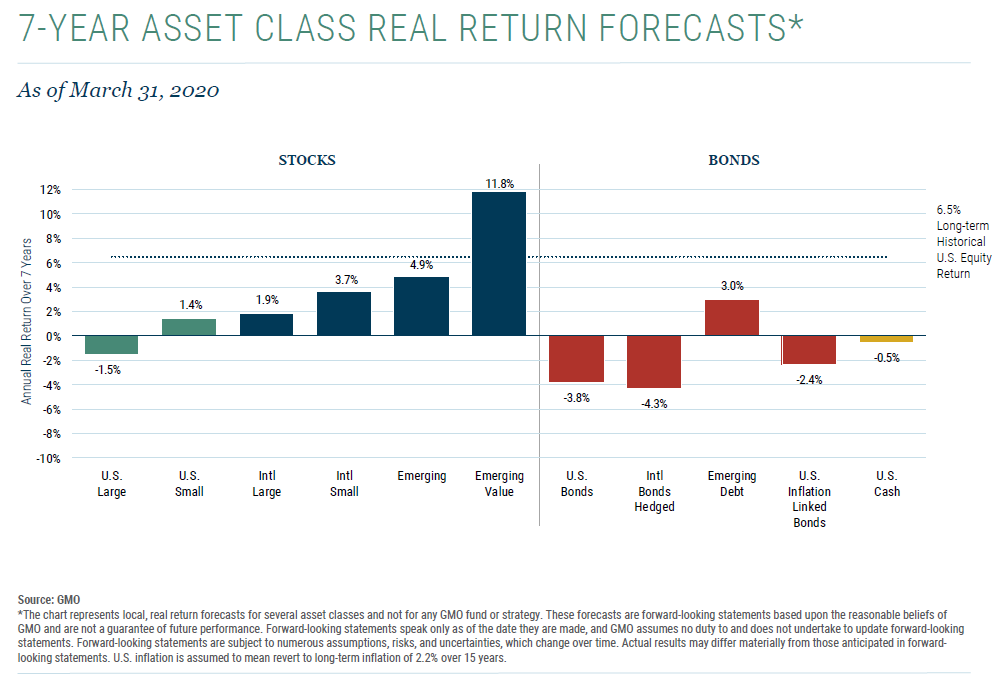

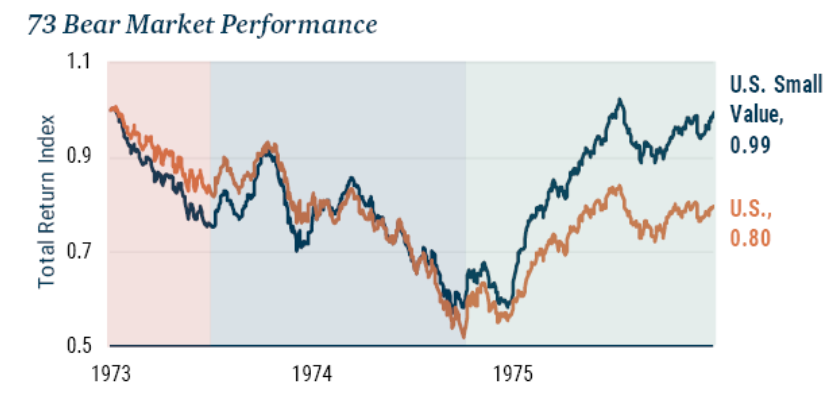

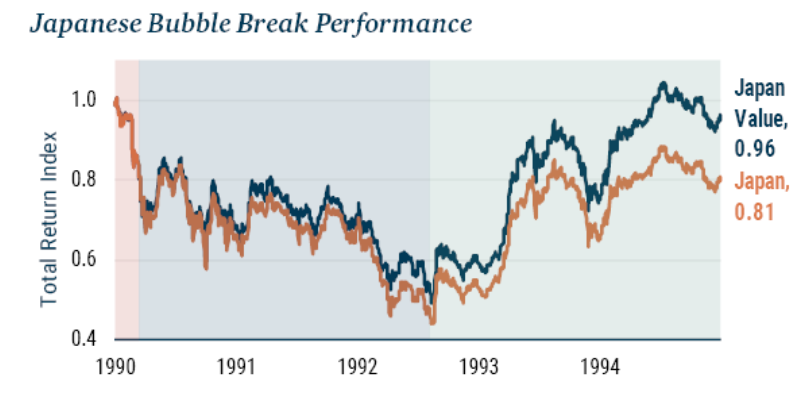

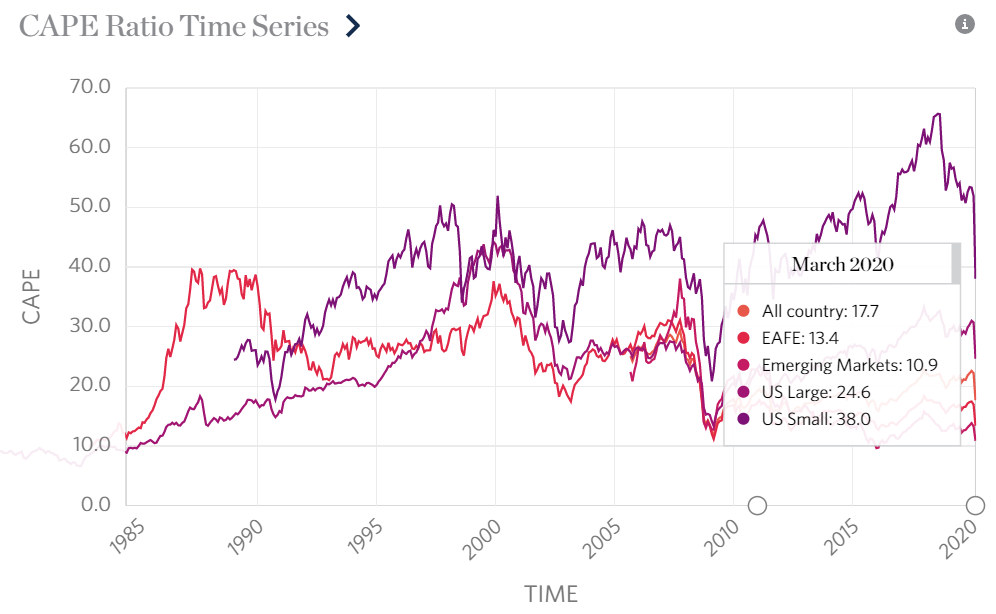

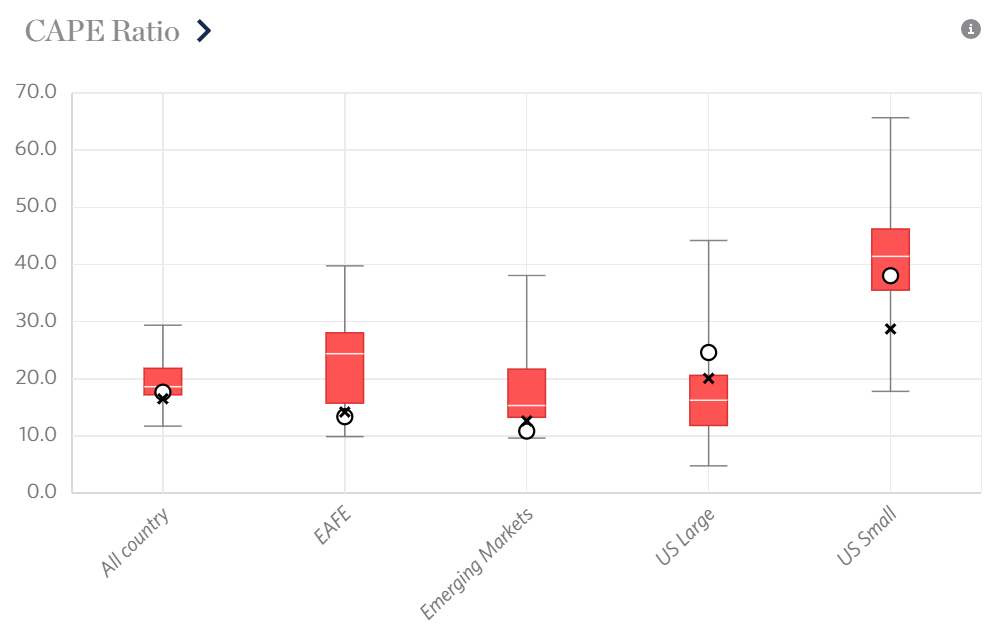

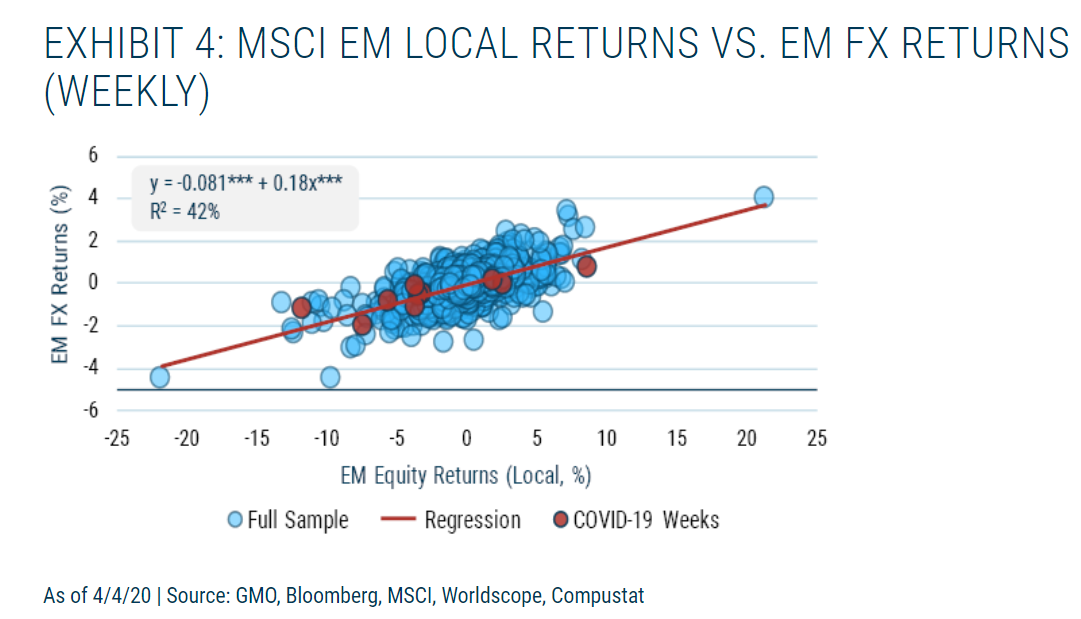

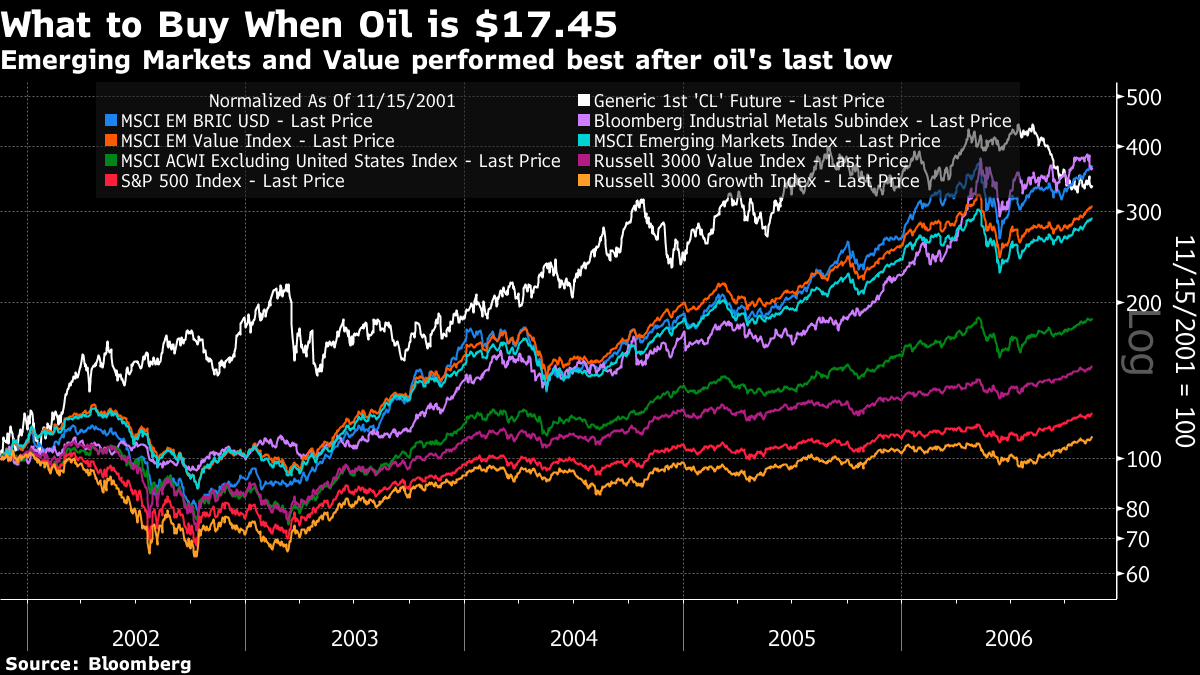

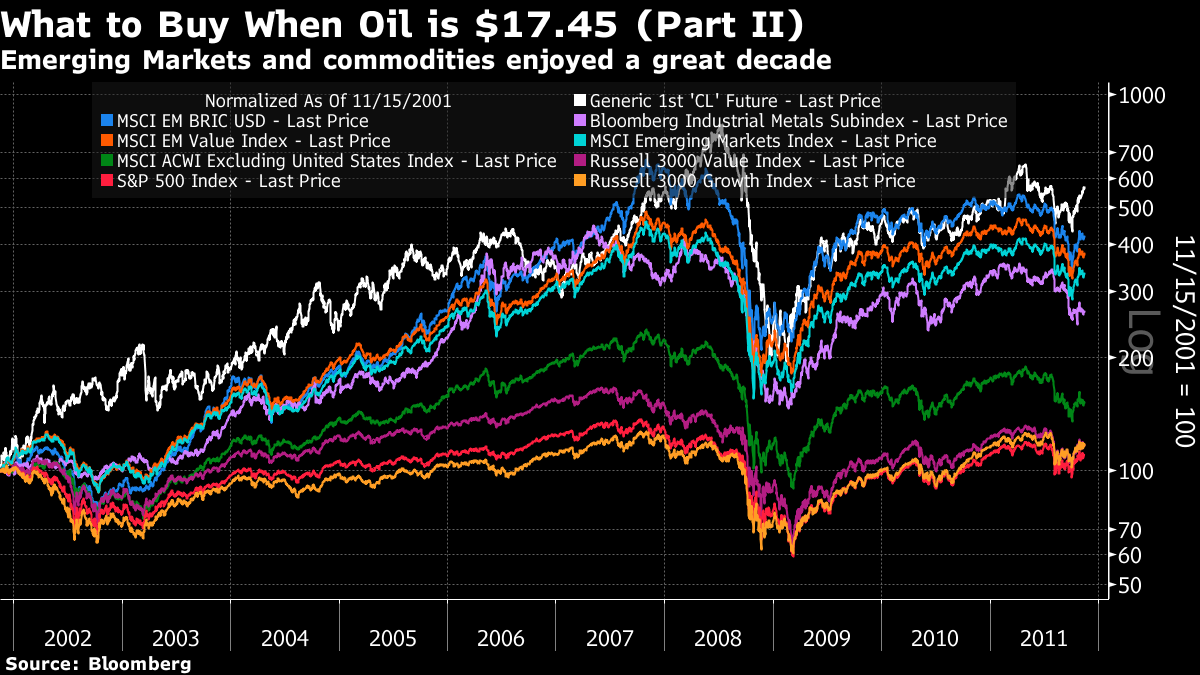

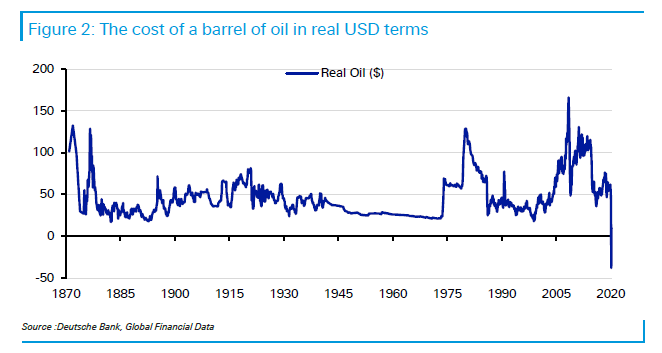

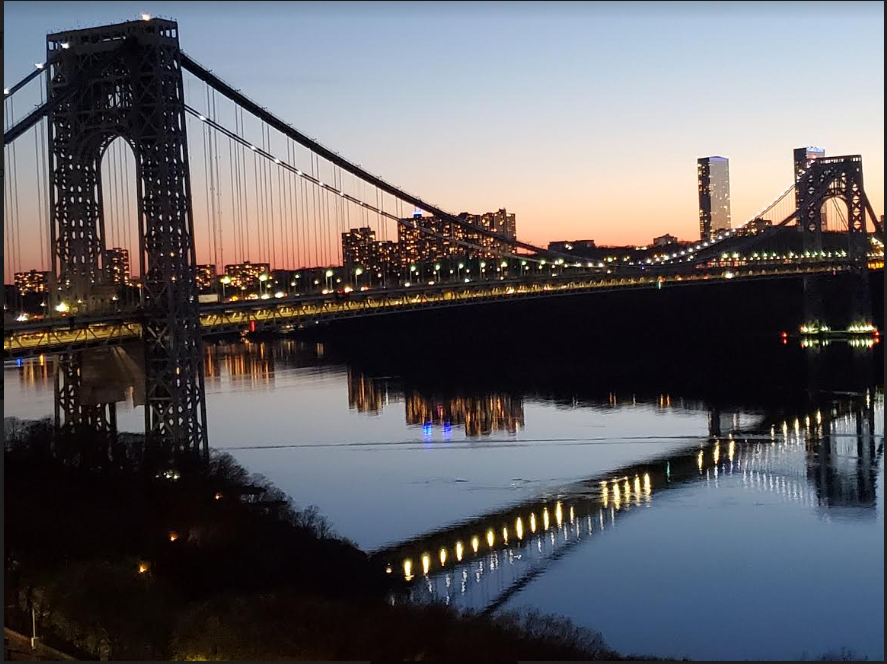

What to Buy Now? With the oil price again positive (never previously regarded as a great reason for celebration), and continuing signs that this wave of the coronavirus is coming under control in the U.S., we had a return to "risk-on" in markets Wednesday. But what exactly should investors be buying for the long term? GMO LLC, the Boston-based fund manager established by Jeremy Grantham and others, regularly publishes seven-year forecasts for asset class returns that it uses to guide allocation. The latest version, published last week, startlingly predicts negative returns for cash and most bonds over the next seven years, and returns of less than 5% for all main classes of equity, with outright negative returns for U.S. large-caps. The only exception, for which GMO is expecting a return of more than 11%, is emerging market value stocks. Unsurprisingly, the asset allocation team headed by Ben Inker say that "Now is the time" for us to act on our portfolios, and fill up on cheap EM equities. Are they right?  The key point is that rebounds from big sell-offs are led by the cheapest stocks. As optimism returns, investors delightedly buy the best bargains, comfortable that whatever factors had made them so cheap in the first place are now less likely to force them to the wall. GMO provide several historic examples, from different eras and geographies. This is what happened after the 1973 bear market, driven by the oil price shock (although that time the shock was upward):  And here is the initial recovery for Japanese stocks after the bursting of that bubble on New Year's Eve, 1989. By 1994, value stocks had briefly made investors whole again once more, although the bear market then resumed in greater savagery:  Now we come to the specific arguments for emerging markets. First, and most importantly, they are cheap. Using cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiples, as advocated by Professor Robert Shiller of Yale University, they are almost as inexpensive as they have ever been, while American stocks look over-priced. The following chart is from the excellent asset allocation website kept by Research Affiliates LLC:  If we compare multiples to history, we find that emerging markets have only been cheaper by this metric 3% of the time since the index's inception. U.S. equities have scarcely ever been more expensive. (Current multiples are shown with a circle; the white line is the historical median, and the X is Research Affiliates' estimate of fair value):  Emerging markets get a further kicker from the currency. Emerging market equity returns are closely correlated to the performance of EM currencies, and that correlation has continued during the pandemic, as this GMO chart shows:  With JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s popular index of emerging markets foreign exchange touching all-time lows, that should mean there is a good chance of a rally for emerging currencies, which would catalyze strong performance from equities. The oil price gives particularly good reason to hope for this. There are no historical precedents for a negative oil price, of course. But returns starting in November 2001, the last time the oil price hit a bottom below $20 per barrel, unrolled in just the way that GMO is predicting will happen this time. This is the performance of a variety of indexes for the five years starting on the day oil hit $17.45 and began to rise. (They are on a price basis, not including reinvested dividends):  This was the era of the "BRIC" concept, which was first named by Goldman Sachs Group Inc. a few days before oil hit its low. MSCI's index of Brazil, Russia, India and China delivered ballistic returns over those five years, as did industrial metals. Value led growth, in EM and in the U.S., and the emerging world far outstripped the U.S., as represented by the Russell 3000 indexes for growth and value, and by the S&P 500. This chart starts more than 18 months after the dot-com bubble burst, and two months after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, but U.S. stocks were still expensive and had a way to go. Naturally, the five-year period stops not long before an epochal financial crisis. So let us now look at 10-year returns. Leadership is barely affected. Value fares much worse within the U.S., largely because banks looked like value plays on the eve of the crisis — but oil still looks like a great investment, as do emerging markets, led by value and the BRICs. The S&P, meanwhile, is barely any higher than it was a decade earlier.  Many might have thought that Ben Inker's seven-year forecasts looked far too bearish. The experience of 2001-2011 suggests that returns along the lines that GMO is predicting could happen very easily. There are still some reasons to doubt GMO's wisdom. Most importantly, plenty of emerging markets have serious problems of their own, and a number are facing up to what could be a serious impact from the coronavirus. Here, Inker suggests that one appeal of the asset class is its diversity. There are a range of different countries, with idiosyncratic issues. When it comes to containing the virus, the list of economies deemed to have done a good job thus far includes China, South Korea and Taiwan, which between them make up more than half of the MSCI Emerging Markets index by market value. If we compare the performance of emerging markets excluding Asia so far this year with MSCI's Asia excluding Japan index, we see that markets are already rewarding the region for its relative success in dealing with the virus. The rest of the emerging markets, down about 40% for the year, at least look as though they have already priced in a severe Covid impact:  Ultimately, it seems to me that the GMO case is well made. Emerging markets tend to behave as geared plays on the global economic cycle, and to move with commodities. Buying them just as oil hits a catastrophic low and the world enters a major recession, when they are almost as cheap as they have ever been, looks like a good idea — at least for those who can afford to wait a few years. Oil in Very Long Perspective How unusual was the action in the oil market this week? Jim Reid, resident financial historian at Deutsche Bank AG, has the answer. He put together the following chart of the real price of oil in dollar terms going back to 1870. As we can see, nothing at all like this has ever happened before:  A barrel of oil earlier this week was effectively cheaper than it was in 1870, when it was chiefly about lighting kerosene lamps and automobiles lay in the future. Over the same period, Reid says, "U.S. inflation has risen 2870% and the S&P 500 31746505% in total return terms." Can there be any other financial asset that is cheaper now than it was a century ago? Looking further at the chart, two things strike me. First, the average price over all of this period, in current dollars, is about $46 — a level through which oil tanked earlier this year. Second, the Bretton Woods period from the war to the early 1970s sticks out like a sore thumb as the truly anomalous period. When oil producers were receiving dollars that had a clear convertibility into gold, the market was dramatically more stable than ever before, or ever since. The period was also marked by financial repression, and tight post-Depression bank regulations in the U.S. Does this period begin to look more attractive? And could we return to it if we wanted to? Survival Tips Facebook has gone badly out of fashion in the last few years. Having once been a joyous place where we could rediscover old friends and enjoy a riotous new form of community, in recent years it has become a site for discord and nastiness. But its flagship service still has the capacity to delight. Facebook's View from My Window page, in which people post views taken from their window, is extraordinary. It is worth exploring. You explore the world and meet other people, without anyone ever leaving home. I haven't enjoyed working from a desk in my bedroom for six weeks, but I am at least lucky that I have a beautiful and ever-changing view. It is that oxymoronic thing, a spectacular view of New Jersey, and it is dominated by the George Washington bridge, which should itself be a sign of inspiration as it was built and completed just as the Great Depression was taking hold, and it is still a vital lifeline for America's biggest city. The sun's light on the Hudson is constantly changing. You are only allowed to post one window photo to Facebook. If anyone has any suggestions for which of these three I should post, I would be grateful. And maybe you should go to the Facebook page for many more views. Late afternoon:  Sunset:  After dark:  And after that, maybe you should go to the Facebook page for many more views from around the world. Be safe out there, everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment