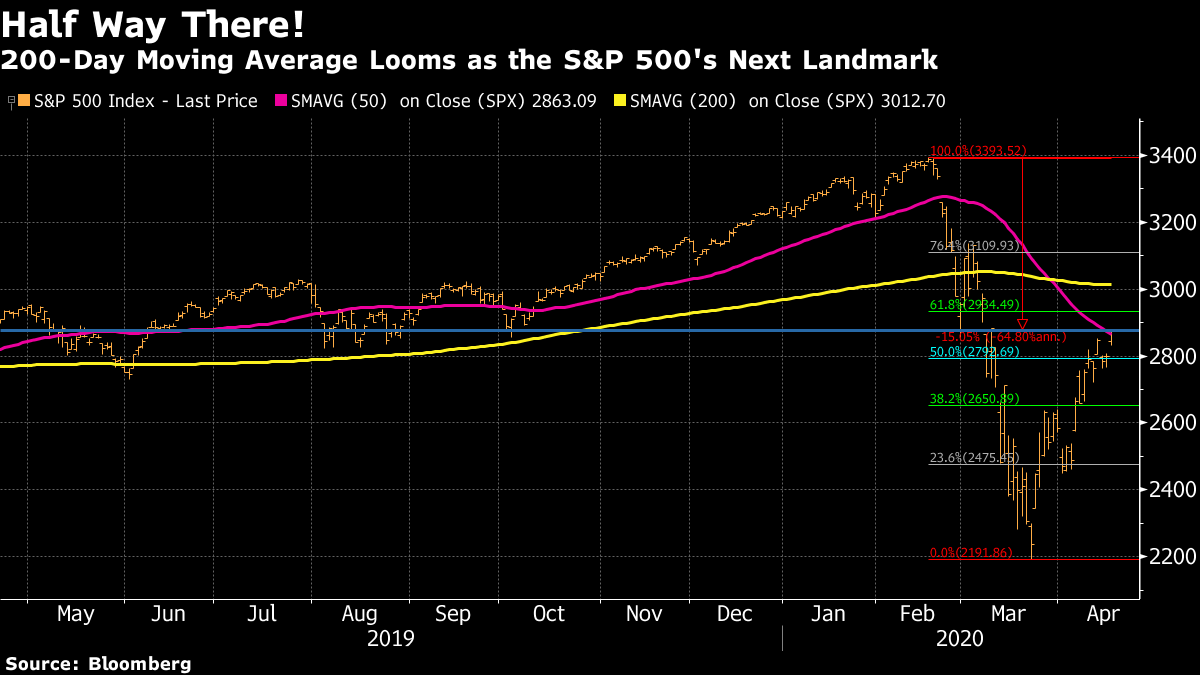

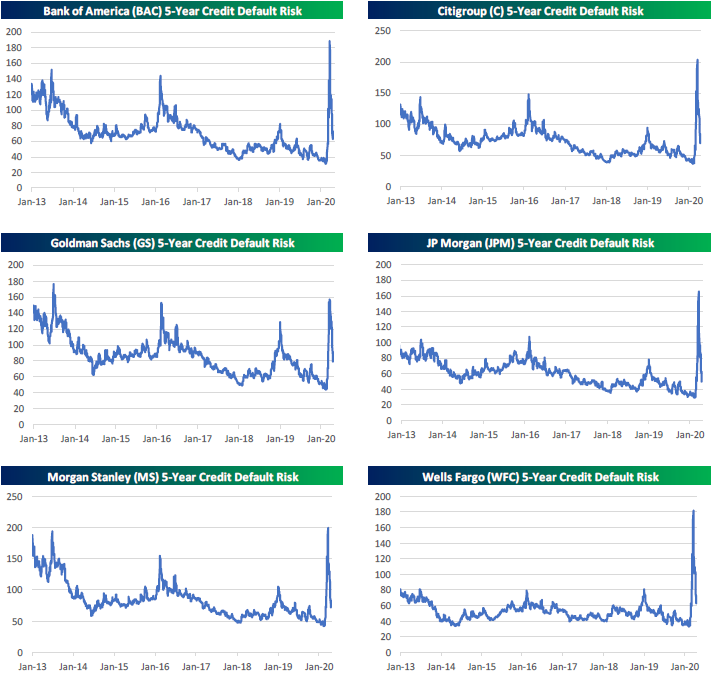

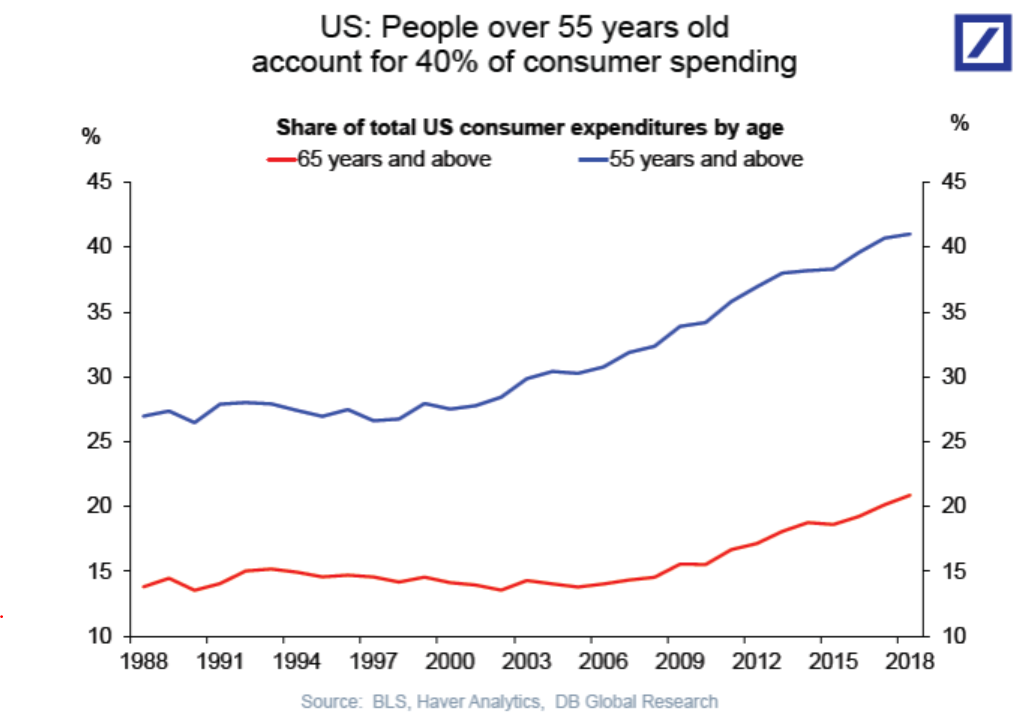

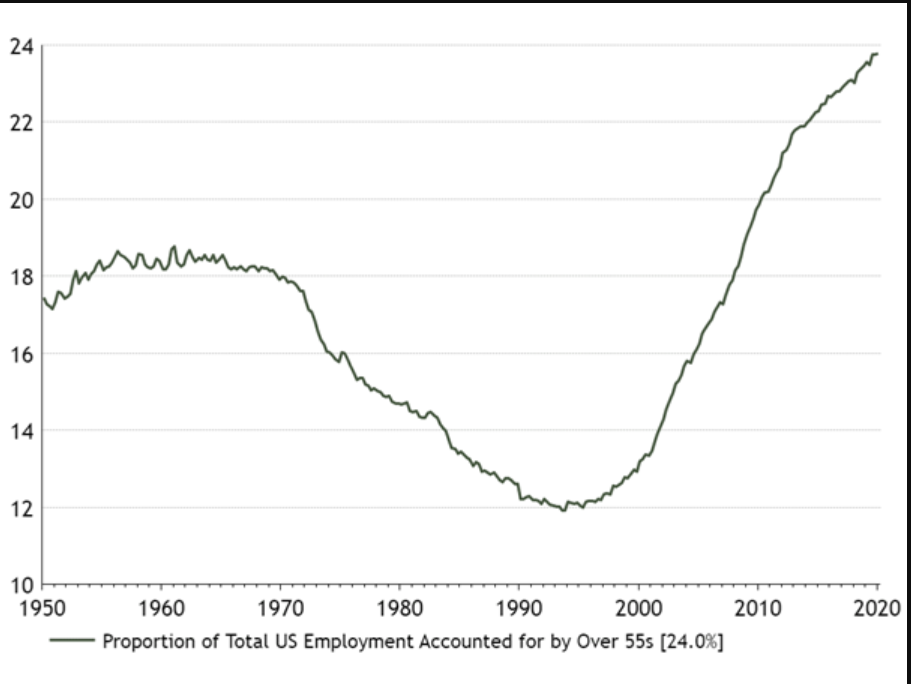

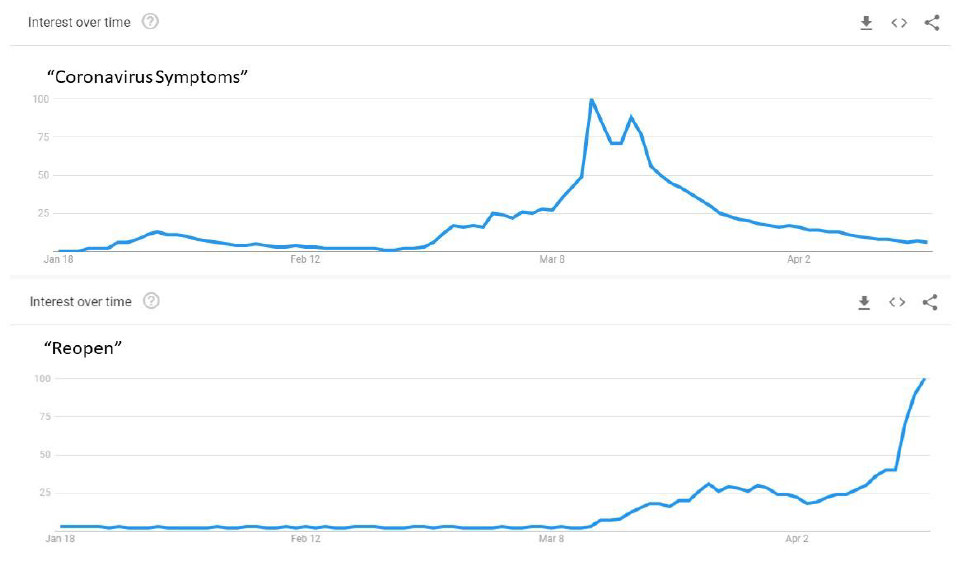

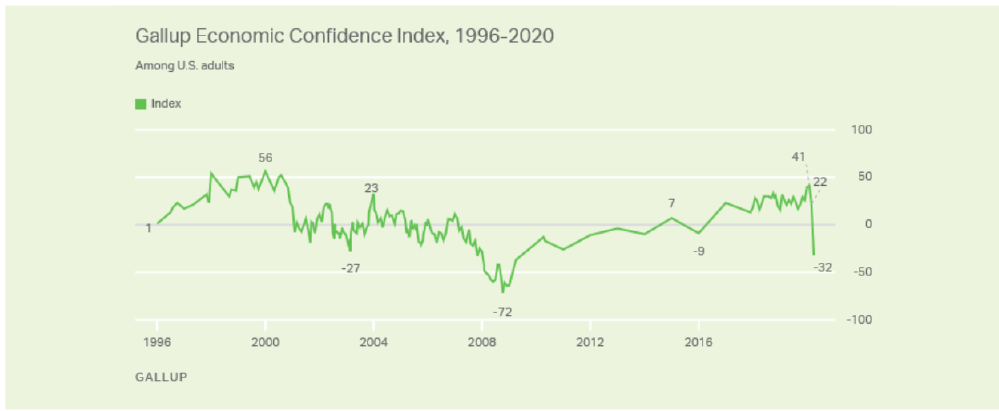

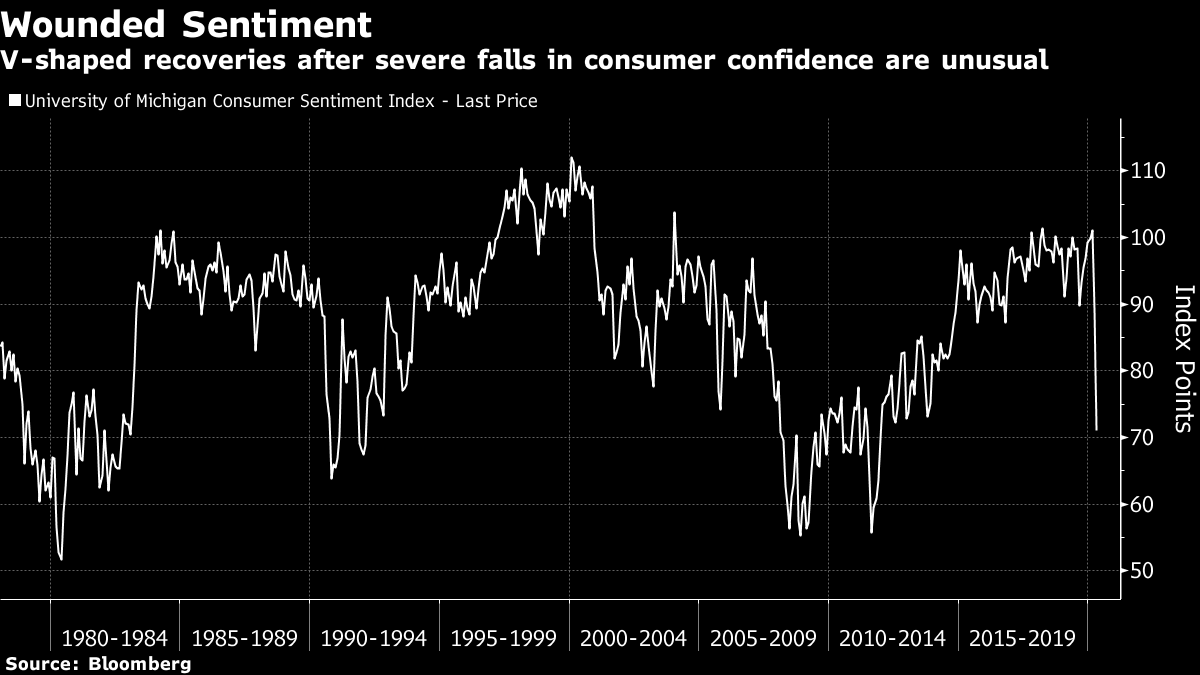

Lessons in Humility Markets have the capacity to make fools of us all. Humility should always be our watchword. Therefore as we brace for another week of trading in global markets, which peaked exactly two months ago, I need to ask how I failed to see the extent of the rally that's underway. Since the Feb. 19 top, the S&P 500 has tanked and then regained more than half of its losses. It's now close to topping its 200-day moving average. If it gets past this landmark, it will look ever more as though this rally is ongoing, and the bottom caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has been reached:  I expected a relief rally, thankfully. I didn't expect anything on this scale. The market itself cannot be "wrong" — it merely aggregates many opinions. But is the predominant opinion wrong, and can this rally have further legs? I generally try to avoid bull versus bear arguments, but on this occasion it's worth summarizing the arguments in favor: It's the Fed, stupid. The scale of the assistance from the Federal Reserve dwarfs anything previously seen. They have the ability to print money. It's best not to ignore them. This argument rings true with those of us who underestimated the Fed's ability and determination to keep asset prices aloft after Lehman. Negative real Treasury yields imply significant financial repression, and a determination by the central bank to push the stock market back up. A credit crisis has been averted. A month ago, there was every chance of a financial collapse to match the post-Lehman disaster. This has been avoided. That justifies a big rally. Just look at what has happened to the default risk of big U.S. banks, in this chart from Bespoke Investment Group:  An all-out medical crisis has been averted. In New York, the epicenter in the U.S., it appears that the worst is past. New York City is by far the most densely populated area in the U.S., where the virus would naturally be expected to spread more easily. The risk of hospitals overflowing has been averted. This takes many risks off the table. Social distancing works; and treatments are on the way. Social distancing has stopped the virus from going truly exponential. This means public health authorities have a handle on how to contain the problem. Meanwhile, several different avenues of research appear to be leading to viable treatments. Politics. This is an election year in the U.S., when political uncertainty often creates difficulties for stock markets. Prediction markets put the race for the presidency at almost exactly a 50/50 tie, after several swings in each direction:  This may actually be a positive, because Donald Trump now controls the levers of the Fed, and will go all out to stoke his re-election bid. True, that involves some market-negative things. Few investors are comfortable with an increase in the tension between the U.S. and China, and politicizing the reopening of the economy has dangers. But a general determination to spend money can only be market-positive. An oil dividend is on the way: The price has tanked, and little seems likely to raise it for a while. That's negative for the U.S. economy to the extent that it drives oil operators, particularly shale drillers, toward bankruptcy. With the Fed refusing to let this happen, however, the effects should be positive. Motorists will have lower gasoline costs. It should act like a tax cut. The same applies across most of Europe, and to emerging markets including China and India. Consumption is ready to begin again. Consumers are desperate to start spending again after a month of incarceration, and the U.S is ready to reopen. The scenes in Michigan and elsewhere show genuine hunger to resume working. The same is true of much of western Europe. Wuhan gives us clear evidence that things can reopen within 90 days. Again, this is much better than the worst scenarios. Added to these fundamental reasons, there are some more practical reasons for the rally. Robo-advisers' asset allocation. Modern pension-saving is done via automatic asset allocation. When stocks rise and bonds fall, such programs naturally rebalance and buy more bonds. This helps to explain the ongoing inflows to bond funds over the decade of the bull market in stocks. Now the same process is helping the stock market. Algorithms are all-powerful. Program-based trading isn't distracted by events in the real world. A program will see that markets are hugely oversold, or cheap on certain metrics, and buy. Now that the rally is gaining steam, algorithms that follow momentum will also want to buy. So the rally can feed on itself. Are these reasonable arguments? Yes. But bear in mind that the Western economy is still in a medically induced coma (to use Paul Krugman's phrase), the coronavirus shows worrying signs of establishing itself in some emerging markets where it could be particularly lethal, and the Chinese return to normal is still a work in progress. China's economy took a historic blow in the first quarter; the effect on U.S. employment has been without precedent. Uncertainty about the future could scarcely be wider. Ultimately, I think this rally has gone too far, for two reasons summarized below: the degree of optimism embedded in the market, and the scale of recovery required to justify that optimism. Valuation Earnings season is underway. As the Covid-19 lockdowns only began in earnest at the end of the first quarter, the full impact won't be apparent. However, if we look at prospective earnings multiples, comparing the S&P 500's level to Bloomberg's survey of estimated earnings for the next year, we see this amazing picture:  On this measure, stocks are their most expensive in 18 years. They have only been more expensive during the historically mad years from 1998 to early 2002. Is this because estimates have been cut back too much? That seems very unlikely. Analysts have been unusually reluctant to update their forecasts in the last month or so. So, if anything, the numbers overestimate earnings. In other words, a "true" prospective price-earnings ratio would be even higher. This chart shows Bloomberg's prospective earnings per share for the S&P 500, going back 30 years:  This cut in estimates is dwarfed by the reduction during the 2008 crisis, when expected earnings were briefly back to their level of eight years before. All that analysts have done so far is knock earnings back to their level at the end of 2017. To buy the S&P 500 now is to buy the stock market at a level as expensive as it was in the climactic years of the dot-com bubble. Optimism for Getting Back to Work Should we really be so confident about going back to work? This is where some humility is needed. The last remotely comparable event happened 102 years ago. Back then, closing down the economy and social distancing simply weren't available as an option. So both economists and epidemiologists are flying blind. Like virtually everyone responsible for allocating capital in markets, I'm not an epidemiologist. But the balance of what I have been reading suggests that a true return to normal won't happen until a vaccine is available, and that is probably a year away. Those particularly at risk, meaning the elderly plus a large swathe of the middle-aged, will still limit their economic activity. Whatever happens, Western economies will be running at considerably less than 100% of capacity for a while — which is another way of saying that they will be in an enduring recession. This chart, from Deutsche Bank AG's chief U.S. economist, Torsten Slok, demonstrates that the relatively elderly account for a large and growing share of American spending:  This chart, from Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. in London, shows that over-55s now account for 24% of the U.S. employed workforce. Again, the message is that the economy will be ticking over at something less than full capacity until we get a vaccine:  Then there's sentiment. What exactly is driving people to show such enthusiasm to go back to work? Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts produced these two Google Trends graphics. Searches for "coronavirus symptoms" peaked last month; now, searches for "reopening" have risen sharply:  Now that people are less fearful of catching the disease, they are anxious to return to work. This comes as Gallup shows a collapse in confidence about their future economic prospects:  The long-running Michigan consumer sentiment index tells a similar story:  When sentiment falls this much, it rarely recovers swiftly. The closest parallel might be the dip in late 1990, caused by Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait. There was a reasonably quick snap-back on that occasion. On the face of it, to expect a similar recovery this time would require a victory over coronavirus as comprehensive as the one over Saddam. That seems very hopeful. Finally, Atwater makes an important point. The U.S. demonstrators who have garnered much attention in the last few days aren't showing confidence and excitement to get back to work. Rather, they are showing anger and despair. Organizing a return to work appears now to be a partisan political issue. Months of extreme political uncertainty may lie ahead. If epidemiologists are right that a second lockdown may be necessary before the election, the immediate future could be ugly. I am not predicting this, merely suggesting that it remains as a realistic risk. We should all be pleased by progress in the fight against the virus. A rally from the low was plainly justified. But to buy U.S. stocks at their current prices requires not healthy optimism, but a denial of the realities that confront us. Survival Tips I am guessing that most of this newsletter's subscribers didn't subscribe to get my poetry tips. I cannot pretend to spend much time reading poetry; it requires too much concentration, and there are better ways to relax. But when it comes to surviving an extreme experience, poetry can be helpful. Clearing books out the other day (like many households, we are trying to de-clutter), I came across a dog-eared copy of Wordsworth's collected poems. It fell open at the following, which has the unpromising title "Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent's Narrow Room": Nuns fret not at their convent's narrow room; And hermits are contented with their cells; And students with their pensive citadels; Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom, Sit blithe and happy; bees that soar for bloom, High as the highest Peak of Furness-fells, Will murmur by the hour in foxglove bells: In truth the prison, into which we doom Ourselves, no prison is: and hence for me, In sundry moods, 'twas pastime to be bound Within the Sonnet's scanty plot of ground; Pleased if some Souls (for such there needs must be) Who have felt the weight of too much liberty, Should find brief solace there, as I have found. It strikes me as speaking directly to our current predicament and gave me some brief solace. I hope it has the same effect on you. More poetry selections would be gratefully received. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment