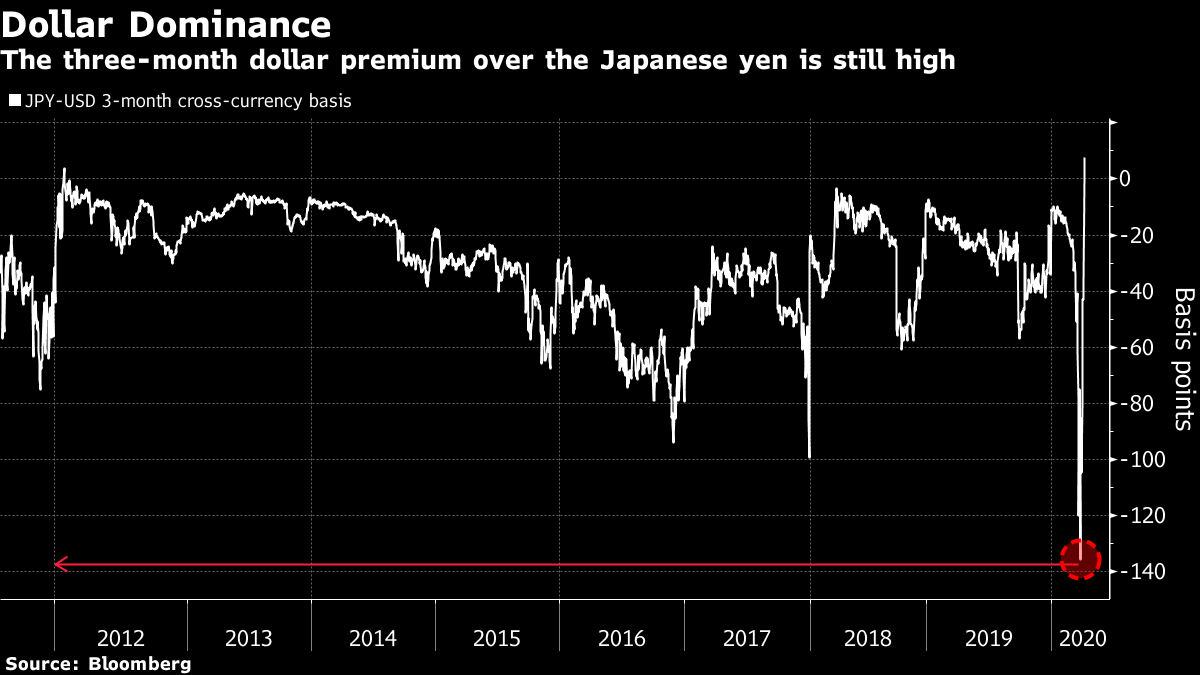

| China concealed the extent of the coronavirus outbreak in the country, according to the U.S. intelligence community. A massive exodus of capital is leaving emerging markets in crisis. And shipping U.S. oil to China now costs half as much as the cargo. Here are some of the things people in markets are talking about today. China has concealed the extent of the coronavirus outbreak in the country, under-reporting both total cases and deaths it's suffered from the disease, the U.S. intelligence community concluded in a classified report to the White House, according to three U.S. officials. The outbreak began in China's Hubei province in late 2019, but the country has publicly reported only about 82,000 cases and 3,300 deaths, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. That compares to more than 189,000 cases and more than 4,000 deaths in the U.S. When China eventually imposed a strict lockdown beyond those of less autocratic nations, there was considerable skepticism toward China's reported numbers, both outside and within the country. The Chinese government has repeatedly revised its methodology for counting cases, and stacks of thousands of urns outside funeral homes in Hubei province have driven public doubt in Beijing's reporting. Globally, cases topped 920,000, leaving more than 46,000 dead. Here are the latest developments on the virus. Stocks in Asia were primed for more declines, following steep losses on Wall Street, as countries moved to implement more stringent measures in a bid to contain the coronavirus. Treasuries climbed with the dollar. Futures in Japan and Hong Kong were lower after the S&P 500 lost more than 4%. S&P 500 futures opened about 1% higher in Asia. Last week's rally in global equities is giving way to renewed selling as companies move to slash dividends and more U.S. states enact severe restrictions on people movement. Elsewhere, West Texas crude fluctuated back above $21 a barrel after President Donald Trump's pledge to meet with feuding producers Saudi Arabia and Russia to support the market failed to bolster prices substantially. A massive exodus of capital from emerging economies has left many in a Catch-22 position: the kinds of monetary and fiscal stimulus measures that the rich world is deploying could perversely make things worse. Interest-rate cuts can help households and companies, but in an increasing number of countries they're driving rates so low that they don't even compensate for inflation — adding an incentive for foreign funds to pull out. And fiscal expansion can raise the kind of funding concerns that still afflict emerging nations, raising the prospect of credit rating downgrades and calls for international rescues. Some $92.5 billion of portfolio investments held by nonresidents flew out of emerging markets over the 70 days starting Jan. 21 — when the coronavirus outbreak began gathering pace in China — Institute of International Finance data show. Outflows in each of the previous three disruptions — the global financial crisis, the 2013 "taper tantrum" over the U.S. phasing out quantitative easing and the 2015 China-devaluation shock — totaled less than $25 billion over the equivalent period. China, the biggest market for electric cars, is considering a reduction in rebates given to buyers and limits on the models that qualify, even as it commits to extending the costly subsidy program for another two years. The country's state council said Tuesday it would extend rebates on electric vehicles until 2022 to support the industry as the coronavirus pandemic hobbles demand. But various government bodies are in discussions over reducing the incentives by 10% later in 2020, according to people familiar with the matter. A reduction in subsidies could temper benefits for the likes of Tesla and Volkswagen AG, which are counting on the world's biggest auto market to buoy sales. Electric-car manufacturers are already facing a host of challenges, from the global pandemic to the plunge in oil prices, which makes internal-combustion vehicles cheaper to drive. The cost of hauling oil from the U.S. to China has skyrocketed to nearly $10 a barrel — almost half of what the American benchmark crude is currently valued at — as the price war spurs a rush for ships. Glencore Plc's shipping arm provisionally booked very large crude carrier Seeb to ship oil from the U.S. Gulf Coast to China in the first half of May at $19.5 million, according to shipbrokers and fixtures seen by Bloomberg. The rate has jumped from $6.55 million in early March as Saudi Arabia booked vessels to unleash a flood of crude and traders scrambled for ships for floating storage. Everything from crude to oil products such as jet fuel is being hoarded due to market structures where later-dated prices are more expensive than prompt contracts, making it attractive to hold supplies and sell them later. What We've Been Reading This is what's caught our eye over the past 24 hours. And finally, here's what Tracy's interested in this morning It should be obvious from recent events that the global financial system is heavily enmeshed with, and reliant on, the U.S. dollar. When everything goes awry, dollars become the de facto coin of the realm and there's often a scramble for them to settle money owed, maintain working capital at companies, or just bulk up corporate cash buffers. What's perhaps less obvious is that the provision of dollars to entities other than banks is not as easy as it looks. Sure, there's a whole host of central bank facilities aimed at pumping dollars into the system (the Federal Reserve's seventh liquidity facility, announced on Tuesday, provides U.S. dollars to foreign central banks. In that sense, it's similar to the currency swap lines already in effect). But all of those facilities rely on the banking system to essentially pass that dollar funding on to end-users at a time when banks are most likely to be cutting down on risk-taking and retrenching from the market.  That's a dynamic that is well-described in the new bulletin from the Bank for International Settlements: "Against the backdrop of strong demand for dollars, the supply of hedging services has fluctuated with the risk capacity of financial intermediaries." In short, as the BIS puts it, "today's crisis differs from the 2008 global financial crisis, and requires policies that reach beyond the banking sector to final users." I'd expect to hear more on this from the Fed soon. (In the meantime, if you're interested in the global role of the U.S. dollar, have a listen to some old Odd Lots podcast episodes here and here). You can follow Bloomberg's Tracy Alloway at @tracyalloway. For the latest virus news, sign up for our daily podcast and newsletter. |

Post a Comment