Mortgage margin calls I suppose the easiest place to start is that one of Donald Trump's real-estate investor buddies is calling on the government to decree that real-estate investors shouldn't have to pay their debts, that's a thing that is happening: Tom Barrack, who a week ago warned that commercial real estate financing was on the brink of collapse because of the coronavirus pandemic, is now calling for a moratorium on margin calls and intervention by the Federal Reserve to keep values of mortgage debt from plummeting further. "America needs the immediate cooperation and support from our banking sector," Barrack, chairman and chief executive officer of Colony Capital Inc., said in a white paper he posted on Medium. Here's the white paper. It's fine, really, I could not resist a little sarcasm above but I don't really object. We talked last week about a commercial real estate investor suing its bank to stop a margin call, and I said that my instinctive sympathies are with the bank—if your stuff loses value, you get a margin call—but I see the investors' point. The Fed is trying to prop up … I was going to say "the commercial mortgage market," but of course I really mean "every single financial market in the world all at once" … and margin calls and forced liquidations are not helpful for that mission. I don't know what is, really; a ban on margin calls—a government decree saying "you can't get your money back" (or "you can't have price discovery," etc.)—is not exactly good for confidence. Some sort of collective voluntary denial of reality—"we all feel so good that we won't even ask for our money back, everything is great, la la la"—probably is good for confidence, but it's harder to coordinate. This story, on the other hand, is much less intuitive: Mortgage bankers are sounding alarms that the Federal Reserve's emergency purchases of bonds tied to home loans are unintentionally putting their industry at risk by triggering a flood of margin calls on hedges lenders have entered into to protect themselves from losses. In a Sunday letter, the Mortgage Bankers Association urged the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the nation's main brokerage regulator to address the problem by telling securities firms not to escalate margin calls to "destabilizing levels." … The rally in prices for mortgage-backed securities that's been fueled by the Fed's large-scale buying is "leading to broker-dealer margin calls on mortgage lenders' hedge positions that are unsustainable for many such lenders," the trade group wrote in its letter to SEC Chairman Jay Clayton and Financial Industry Regulatory Authority President Robert Cook. … The MBA letter, signed by Chief Executive Officer Robert Broeksmit, said that when lenders issue new loans, they often simultaneously short mortgage-backed securities. This is done because the loans might fall in value before a banker can sell them to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The bet against mortgage bonds helps protect the lender if that happens, Broeksmit wrote. Now, with lenders getting crushed on these hedges, they're facing a wave of demands from brokers that they sell holdings or put more money in their trading accounts. "Broker-dealers' margin calls on mortgage lenders reached staggering and unprecedented levels by the end of the past week," Broeksmit wrote. "The inability of a large set of responsibly-managed lenders to meet these margin calls would jeopardize the very objective of the Federal Reserve's agency MBS purchases -- the smooth functioning of both the primary and secondary mortgage markets." The idea is that when a mortgage lender makes a loan, it will lock in its interest rate by selling mortgage bonds. (It gets long a mortgage in the primary market, by lending, so it gets short an offsetting mortgage in the mortgage-backed-securities market.) That way it should have no interest-rate risk as the mortgages it makes move through the pipeline, being packaged up and put into securities and sold. The lender isn't taking mortgage rate risk; it is just in the business of turning market mortgage rates (measured by prices of mortgage-backed securities) into actual new mortgages. The counterintuitive problem for mortgage lenders isn't exactly that the value of mortgages has gone down like most other financial assets. It's that the value of mortgages has gone up, because the Fed got worried about the (agency residential) mortgage market (and, again, every other market) and started buying a ton of mortgage-backed securities, pushing the prices of those securities way up. If that happens while a lender has new loans in the pipeline (and is short a bunch of mortgage-backed securities), the lender will have a big mark-to-market loss on its short position. It should theoretically have an offsetting gain on its long position: When it finally sells the mortgages it originated, it should be able to sell them for a much higher price than it initially locked in.[1] But that takes time, and, crucially, the two trades have different margining regimes. The short position is done in the mortgage-backed-securities market, through a bank or broker that will demand daily collateral when the short moves against the lender. The long position is done through whole loans, which don't trade in the market with a market price (until the lender packages them), and it isn't funded through a margin account at a broker. (It's funded with the lender's own money, or more likely by borrowing from a warehouse line at a bank.) When mortgage bonds go up in value, the lender has to come up with cash for its short immediately. When the lender's loans go up in value, no one gives it any extra cash that day; it has to wait until it finishes packaging and selling them. And so the Mortgage Bankers Association wants banks not to call margin on short sellers of mortgages that have gone up in price, while Tom Barrack wants banks not to call margin on long holders of mortgages that have gone down in price. Everything is unsettled in every direction, and everyone wants a little time out on their obligations. By the way, there are two other general lessons of that MBA letter. One is that, in a crisis, extremely safe trades can be undone by different margining regimes. If you are in the business of buying widgets and selling widget futures, in ordinary times that will be a very safe trade because the price of widgets and the price of widget futures will be almost perfectly correlated. But if widget (and widget futures) prices suddenly move around a lot, and if the lender who funds your widget purchases is different from the clearinghouse that provides your widget futures exposure and they have different rules on collateral, then you might find yourself having to come up with a lot of cash on the losing side of your trade while not getting any (immediate) cash on the winning side, and then even a perfectly correlated trade—one that is guaranteed to pay out in full in the near but not-near-enough future—can blow up. The other good general lesson is about short selling bans. When financial markets go haywire, people always call for bans on short selling in the stock market. These calls are wrong. One reason they are wrong is that short sellers are good for price discovery, they root out fraud, they make prices accurate in a way that can inspire confidence, blah blah blah; you can find these arguments unconvincing, it's fine, price discovery may not be what we want right now. But the other reason not to ban short selling is that short selling is so often a crucial piece of the plumbing of markets; it is so often critical to the production of real stuff in the economy, or at least in markets. When the price of mortgage bonds started going down, you could imagine saying "we should ban short selling of mortgage bonds to keep the price up"—but that would have had the effect of preventing mortgage lenders from making loans, because short-selling mortgage bonds is a critical part of the machinery by which they produce those loans. So, instead, the Fed just bought a whole lot of mortgage bonds, which also messed with that machinery. Corporate lending One thing is that if you loaned a company money back in the good times, there's a good chance that you can demand your money back, now, in the bad times. Like for one thing they probably have to pay you interest, and they might have trouble doing that, and so you can put them in default. Even that aside, you might have some sort of maintenance covenants requiring them to have a certain amount of income or leverage levels or whatever, and now, in the bad times, they are probably violating those covenants and you can put them in default. Some good general advice—not investing advice, really, just sort of ethical advice—is: Try not to do that. Those companies need that money! Taking it back from them will only make everything worse! In North America, at least a dozen direct lenders are considering or have agreed to specific concessions such as switching to alternatives to cash for interest payments or relaxing pre-payment penalties, according to people familiar with the matter. Some who work primarily with private equity-backed companies are resisting making any changes like considering relaxing payments or waiving future covenants unless the firm's sponsors put in more capital or provide fund guarantees, said the people, who aren't authorized to speak publicly. ... "For anybody that's taking a hard line, whether it's a mortgage company or a private credit line, not giving some degree of flexibility, there's probably a special place in hell for those guys," JB Capital founder Jeremy Hill said. JB Capital is a "lower-middle market lender." When a lender says that there's a "special place in hell" for lenders insisting on the letter of their contract, times are weird. Another thing is that if you are a company and a bank gave you a credit line back in the good times, you can draw on that line now and have more money, which would probably be good for you. (Though see the point above—make sure they can't demand the money back because you've breached a covenant!) Having more money, in a global cash crunch, is better for you than having less money. I have … less of a moral objection to doing this, if you can? Like, you might need that money more than the banks do. On the other hand the banks do need the money, and if they ask you nicely, maybe you should hold off: The biggest U.S. banks have been quietly discouraging some of America's safest borrowers from tapping existing credit lines amid record corporate drawdowns on lending facilities, according to people familiar with the behind-the-scenes conversations. For Wall Street, it's not an issue of liquidity so much as profitability. Investment-grade revolvers -- especially those financed in the heyday of the bull market -- are a low margin business, and some even lose money. The justification is that they help cement relationships with clients who will in turn stick with the lenders for more expensive capital-markets or advisory needs. That's fine under normal circumstances when the facilities are sporadically used. But with so many companies suddenly seeking cash anywhere they can get it, they're now threatening to make a dent in banks' bottom lines. So far, it seems some corporations are willing to oblige, turning instead to new, pricier term loans or revolving credit lines rather than tapping existing ones. McDonald's Corp. last week raised and drew a $1 billion short-term facility at a higher cost than an existing untapped revolver. The rationales will vary from borrower to borrower, but market watchers agree that for most, staying in the good graces of lenders amid a looming recession is important. … "The banks are open but if everybody asks at the same time then it's going to be difficult from a balance sheet perspective," Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Arnold Kakuda said in an interview. Still, the significant capital requirements needed to fund tapped facilities and the strain mass drawdowns put on profitability as bank funding costs rise and the macro backdrop worsens remain the main driver, said the people familiar with the matter. "The corporate banker doesn't want everybody to take a hot shower at the same time in the house," said Marc Zenner, a former co-head of corporate finance advisory at JPMorgan Chase & Co. "They want to use their capital where it's most beneficial." It is a little bit of a heartwarming story, isn't it? The banks, in good times, give companies underpriced revolving credit lines as a gesture of friendship. Then, in bad times, the companies do not draw on those lines—they go out and get higher-priced credit elsewhere—as a reciprocal gesture of friendship.[2] If you combine the two transactions you get … nothing? Except the symbolic expression of friendship? (And, fine, some commitment fees for the banks.) Like the banks promise the companies to lend them money, which makes the companies happy, and then the companies don't borrow the money, which makes the banks happy. Everyone feels more closely connected to each other, more secure in their relationship, without any money actually changing hands. Stock prices The S&P 500 Index closed last week down about 25% from its highs of just over a month ago. Here is a fun chart from Scott Bauguess of the University of Texas showing that a bit more than all of that drop happened in the first five minutes of trading each day:  via Scott Bauguess on LinkedIn via Scott Bauguess on LinkedIn If you had bought stocks at 9:35 a.m. each day and sold them at the close, you'd be up a little bit over the past month and a half. If you bought them at the close and sold them at 9:35 a.m., you'd be down about 30%. That feels right, doesn't it? The story of the past month or so has involved a lot of limit-down moves in futures overnight, followed by limit-down moves in the stock market in the first few minutes of trading, followed by 15-minute pauses and then calmer trading—anchored at the new lower price—the rest of the day. Also some up moves too though, but those too tended to involve limit-up futures moves the night before. After the first of those limit-down moves, on March 9, I wrote: The market did not fall 7% by 9:34 a.m. today because of shocking news that came out at 9:32! Investors had all weekend to ponder coronavirus news, and all of Sunday to ponder oil-price news, and they pondered it at their leisure, and futures traded limit-down, and then the stock market opened and investors applied their weekend's worth of pondering to the market, with the result that the market shut down four minutes later. A weekend of pondering, four minutes of trading, 15 more minutes of pondering. I am not sure what you learned in the 15 minutes that you didn't learn over the weekend. Still, stocks rallied a bit after the re-opening, so I guess it worked. One way to put it is that most news happens in the evening and early morning, it gets synthesized and analyzed overnight and before the stock market opens, and then it is all incorporated into stock prices in the first five minutes of trading. After that everyone sort of hangs out in the market just in case, or they buy or sell stock at the prices that were established in the first five minutes. The first five minutes are where it's at. You could—as I've said when we've discussed this previously—just smush all the trading into those first five minutes and give everyone the rest of the day off. They wouldn't exactly have it off, they'd have to spend all that time incorporating and analyzing and synthesizing information, but the actual trading part seems to reset prices pretty quickly. By the way there's a really wild paper by Bruce Knuteson—we discussed a version of it a few years ago—about how global stock markets, over the last couple of decades, have been up a lot overnight and down a little bit intraday. Knuteson attributes this to vast and subtle market manipulation, but the simpler explanation of "people think about what they're going to do overnight, and then do it when the market opens" also sort of fits the data—and explains why, when the market is down a lot, it goes down mostly overnight too. Activism The divide between the Before Times and the After Times is so stark and sudden that so many stories now take the form "people started stuff in the Before Times, and that stuff makes no sense in the After Times, and they are awkwardly scrambling to get out of whatever they started." Sometimes stories like that involve contractual commitments—merger agreements, credit lines, SoftBank Group Corp.'s WeWork tender—that are hard to get out of, because the thing that makes no sense for you in the bad After Times (giving someone lots of money) makes a lot more sense for your counterparties (who need the money), so they don't want to let you out of it. Other times though there is no obstacle to dropping the whole project, you can just walk away, no one will complain, there is just maybe a faint sense of embarrassment: Being a shareholder activist investor isn't such a good look right now. Executives are struggling to keep their companies afloat and their workers employed as the coronavirus spreads, and activists' demands in many cases seem less pertinent than they did just a few weeks ago. That's led many of the investors to walk away from campaigns or settle them early. ... The shift comes at a normally busy time for activists, known as proxy season, when they have the opportunity to nominate directors ahead of annual meetings that tend to take place in the spring. This year, however, it falls as companies are focused on keeping employees safe and making payroll as revenue dissipates. "This company needs to optimize its capital structure by levering up to buy back a lot of stock" is a thing you could have said with a perfectly straight face like a month ago, and now you can't, and if you said it a month ago and entered into contentious negotiations with the board about whether it would happen and how much, now you just have to call them up and say "yeah never mind, stay safe, see you next proxy season." Things happen Zoltan Pozsar and Perry Mehrling On The Historic Crisis Of Financial Market Plumbing. The Fed Brings the Global Financial System Back From the Abyss. Fed Releases Details of BlackRock Deal for Virus Response. Failed ventilator project. Oil Plummets to 17-Year Low as Broken Market Drowns in Crude. One Corner of U.S. Oil Market Has Already Seen Negative Prices. Surveillance of Homebound Wall Street Traders Relies on Pen and Paper. Making Corporate America Hold Cash Is the Wrong Way to Prepare for Crises. Scary Times for U.S. Companies Spell Boom for Restructuring Advisers. WeWork's Imperiled $3 Billion Stock Sale Would Mostly Benefit 5 Investors. VIX trades have gone well this year. Hidden Chinese Lending Puts Emerging-Market Economies at Risk. When central banks take over securities markets. Bosses Panic-Buy Spy Software to Keep Tabs on Remote Workers. Stuck-at-Home Americans Get Robbed Less Often, But Fight More. Coronavirus art heist. WHO thinks alcohol is an 'unhelpful coping strategy' for coronavirus cabin fever. "Two weeks ago, Matt Levine's immediate concerns centered on where to find the best happy hour and coolest DJ." If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] I mean, assuming that they are conforming and can get government guarantees and be sold in the usual manner. You might think "well the credit quality of new mortgages has gone down a lot since people are losing their jobs and income, so the lender shouldn't be able to sell them for the same price as existing government-guaranteed mortgages," but that doesn't especially seem to be the concern here. [2] Also honestly if you can raise higher-priced money elsewhere now, and *keep access to your revolver*, that's good for you too. You never know if, next week, you won't be able to raise even higher-priced money elsewhere. The point of the revolver is to have access to cash in bad times; if the bad times come and you still have access to cash elsewhere, why not keep the revolver untouched in case of even worse times? |

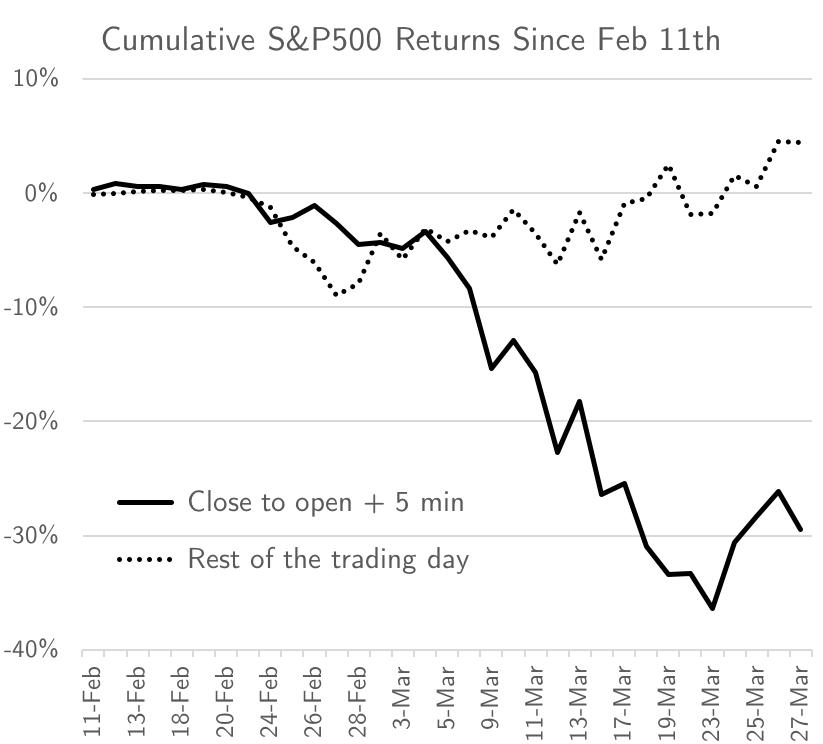

Post a Comment