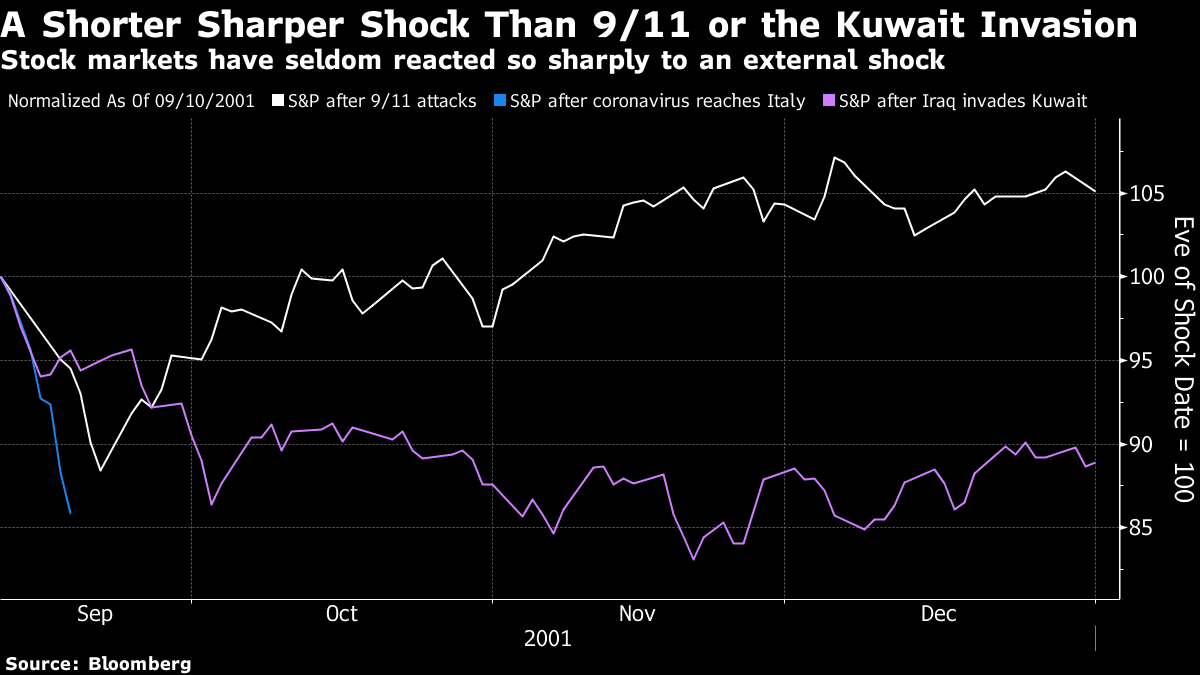

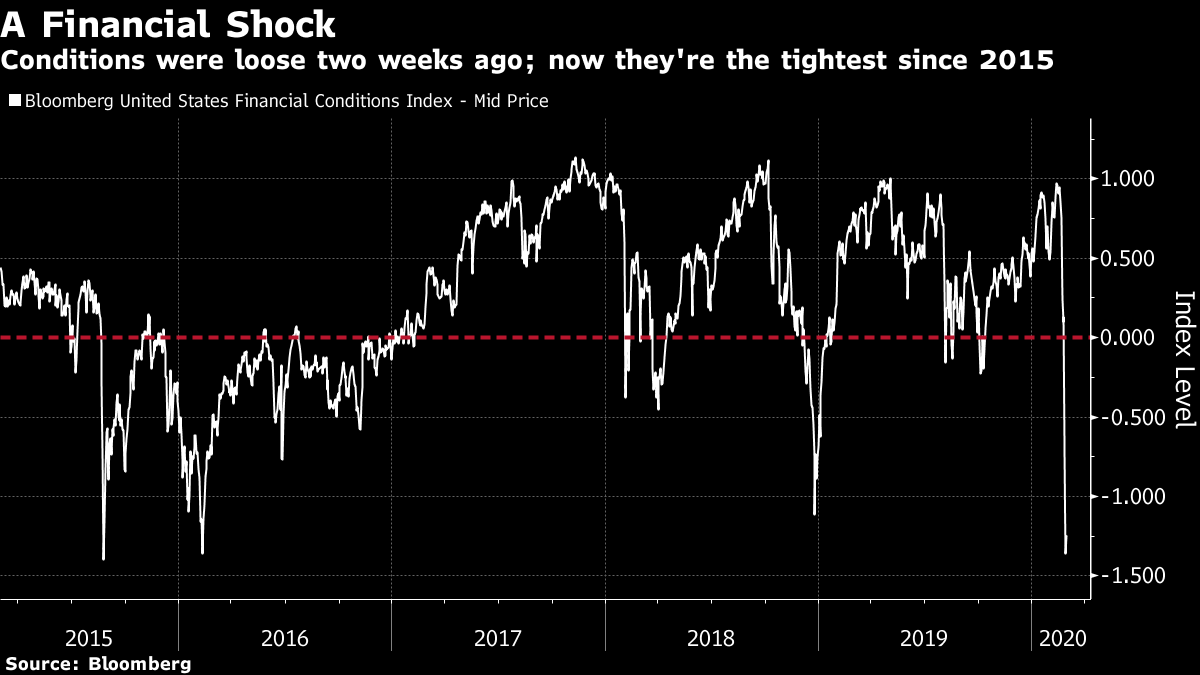

Buy When There Are Germs in the Street? What lies ahead? And when will we turn? Let me try to answer this both in the short term ("When will risk assets enjoy a bounce after such a savage selloff?") and the long term ("How bad will the total damage eventually be?") The answers depend to a great extent on the coronavirus, of course. It is hard to see how a sustained recovery can last without clear evidence that it has at last done its worst. But the virus's effect on markets is indirect, and works through its effect on the economy, rather than through its terrifying effect on the health of humans. And markets are unused to dealing with external surprises like this, the greatest exogenous shock at least since the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001. They are bound to make mistakes as they adjust their forecasts for the economy, and there should be money to be made by betting against their judgments. So, what are the short-term prospects? This has been one of the swiftest stock market corrections on record. After a sudden fall, the physics of markets generally dictate that prices will enjoy what is tastefully known in trading rooms as a "dead cat bounce" (so called because even a dead cat will bounce if you drop it far enough). And there are plenty of contrarians out there who want to follow the advice attributed to Rothschild and "buy when there's blood in the street," or indeed the advice of Warren Buffett to be "greedy when others are fearful." Using more technical market jargon, there can come a moment of "revulsion," when the narrative becomes so skewed and overwhelming, that it sets the conditions for a rebound. To put this in context, this is a sharper reaction by U.S. equities than was seen even after 9/11, or Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990:  Meanwhile movements in bond markets have been even more dramatic. In early trading in Asia on Monday morning, the 10-year Treasury yield dropped to the previously unfathomable level of 1.04%, before rebounding. It has never in history dropped below 1%.  This has the look of revulsion about it. It isn't necessary to apply psychology to predict a rebound. The pattern of trading in the last week suggests that the market is now "oversold" which, to borrow the phrase of Deltec Bank & Trust Ltd.'s Hugo Rogers, means that prices are at "lower levels than warranted by the deterioration in fundamentals (thus far)". He points out that many traders are buying protection at high prices in the option markets, and selling whatever is showing a profit and has the liquidity to be sold in a hurry — which means equities and even, for the last few days of last week, gold. That enables them to hedge the most illiquid parts of their portfolio, such as high-yield bonds. This setup should be followed by a snapback, in Rogers' words, "particularly if there are discernible catalysts (e.g. rate cuts or a snap back in activity in China)." At the time of writing, equity markets have shown that they can indeed snap back swiftly in response to the traditional stimulus of central bank intervention. The S&P 500 rallied impressively into the close Friday after the Federal Reserve released a statement saying that it was monitoring the coronavirus, as this screen shot of the day's trading shows:  Then in Japan, after Asian trading started Monday with another jolt downward, a statement came that the Bank of Japan would "strive to provide ample liquidity." That was enough to turn a loss for Japanese stocks on the session to a substantial gain, which was followed by increases in other markets across the region. (Meanwhile, extraordinarily, mainland Chinese stocks almost eliminated their losses for the year.) Could central banks really provide a catalyst? This isn't a crisis that can be resolved with a change in monetary policy; the virus is impervious to cheaper money. But in the short term, the fall in risk assets has meant a sharp tightening in financial conditions, even though bond yields are lower. Bloomberg's measure of financial conditions (where numbers are above zero show easy conditions, while negative numbers show tight financial conditions), demonstrates the extent and suddenness of the shock. Money hasn't been this tight since the Chinese devaluation crisis of 2015:  Easier money should release the pressure (to use Jim Cramer's famous phrase) on dealers holding illiquid debt, and also make life easier for heavily leveraged companies. It would reduce the risk of this financial shock turning directly into an economic shock unaided by the virus, by averting the risk of forced selling and forced bankruptcies. It would also allow central banks to show that they retained some power over the situation. None of this means that the Federal Reserve or other central banks could end the market and economic crisis on their own. But they are still likely to act, and to cause some kind of a trading rally from oversold levels when they do. A Bear Market Bottom? Nobody thinks that a bear market bottom (and therefore a classic long-term buying opportunity) is anywhere close. The all-time high was only last month, for U.S. stocks, and we are only about 12% below that. But the virus raises real questions about the risk of a recession, and also of a bear market. The latest Bloomberg book club selection, which we will be discussing in a live blog on the terminal Tuesday, starting at 11 a.m. New York time, is Russell Napier's Anatomy of the Bear, an analysis of how the four greatest secular bear markets of the 20th century (as he diagnoses them) came to an end, and how it might have been possible to spot an historic buying opportunity in real time. It casts considerable light on how bear markets start and end, and that is useful for the present moment. Are we entering a true bear market? One necessary condition, common to all, is a recession, in economic activity and in company profits. If the coronavirus is enough to tip the world economy into recession, then we can expect a long-lasting bear market. It will be a while before we can make that judgment, but this week will bring the first wave of economic data which will have been impacted to some extent by the virus, and the outlook isn't cheery. Friday brought China's official PMI data from purchasing managers. Analysts' opinions were widely divided ahead of time; in the event, the numbers for manufacturing, and particularly for services, were the worst on record:  The Caixin PMI, which covers more smaller companies, was published early Monday and was only slightly better. These numbers are spectacularly bad. Australia's PMI subsequently showed that "demand conditions weakened further" in February, and that inflows of new orders "fell at the fastest pace since the series started in May 2016." That ended six months of Australian export growth. This is a serious economic shock, then. The welter of European and U.S. data that will follow this week, however, won't give us much more evidence, as the spread of the disease only became clear in the last week of February. The market isn't going to make a lasting recovery until it becomes clear that we have avoided a recession. That's the key long-term question. Napier's analysis of how bear markets start is fascinating. Simply put, they start when equities have become too expensive, according to long-term metrics, and end when they are too cheap. U.S. equities are, of course, very expensive. Valuation doesn't help with timing in itself, but does help assess the likely scale of the damage. The higher stocks start, the further they fall. When it comes, the end of a bear market is nothing like a "dead cat bounce" or trading rally, and isn't met by any great "revulsion" or overwhelming negative sentiment. Instead, bull markets take over once more once all hope has been lost, and investors have lost interest. In conditions of apathy, investors don't even notice at first that things have started to improve — and then the rally can begin. We are a very long way from such a point. One other fascinating finding from re-reading Napier's book concerns the Spanish flu, by far the worst pandemic of the 20th century and the realistic worst-case scenario that now confronts us. It lasted roughly from January 1918 to December 1920, and the first great bear market bottom in the book happens in the summer of 1921. Yet Napier never mentions the flu, and it doesn't appear in the copious news articles he cites from the months when the nadir had been reached. The flu might well have contributed to the brief economic depression that began the 1920s, but that bear market can be explained without reference to it. Instead, Napier focuses on the difficulty investors had in assimilating the role of the Fed, then a brand-new institution, and understanding the impact of huge amounts of government debt issued to fund the war. Plainly there are close parallels with today's confusion over the new active role that central banks have taken since the crisis, and the effect this has had on growth, profits and valuations. For one example of how difficult it has become to understand the signals that markets are sending, the 30-year bond yield is now lower than the dividend yield on the S&P 500 — an extraordinary fact that should mean that equities are a screaming "buy." The only previous time it happened was at the worst of the financial crisis in late 2008 and early 2009. Yet this time, it has happened within weeks of an all-time high. This creates the same kind of dissonance and confusion that a century ago was created by the arrival of the Fed, and the escalation of war-time borrowing. It is dangerous.  It is human nature for all of us to look at the advance of the virus and try to work out how serious its toll could be. For the long-term future of the market, we just need to know about its economic impact. We are only at the start of trying to work that out. Please join us on the terminal Tuesday to discuss more of the lessons of history with Russell Napier. Send questions and comments to: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment