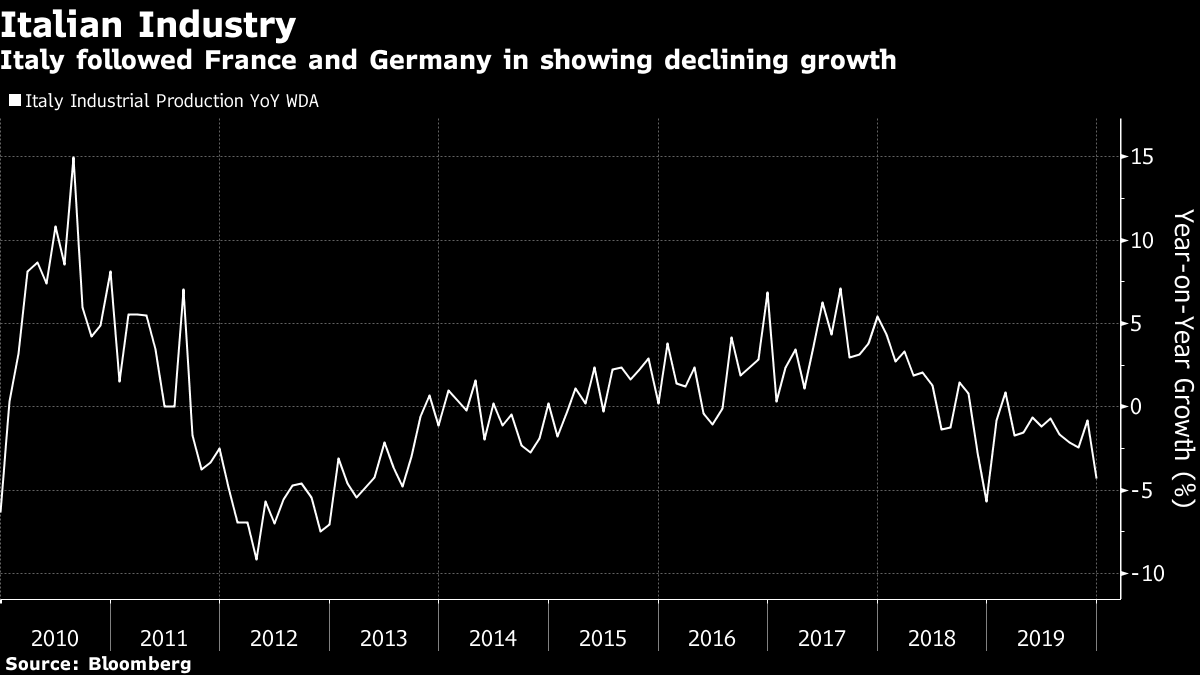

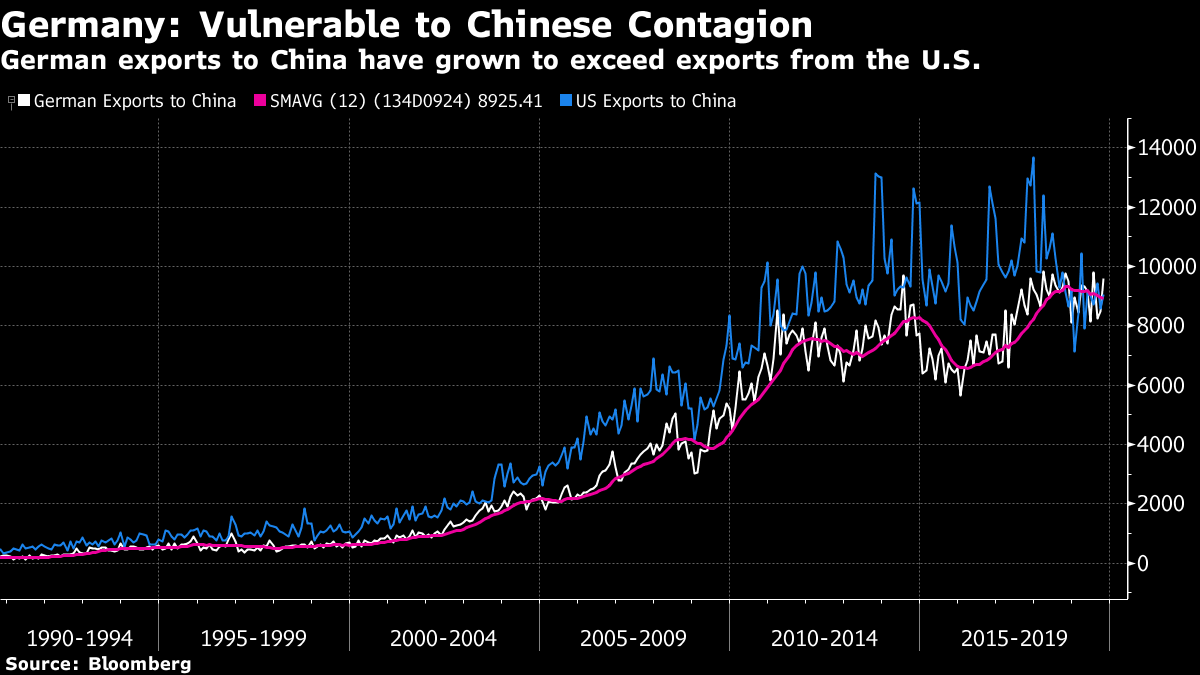

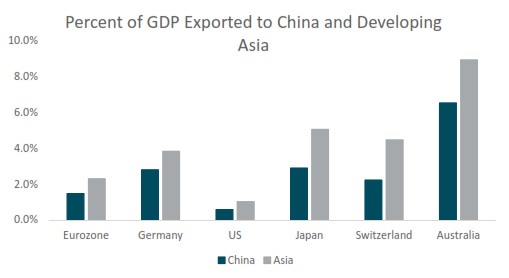

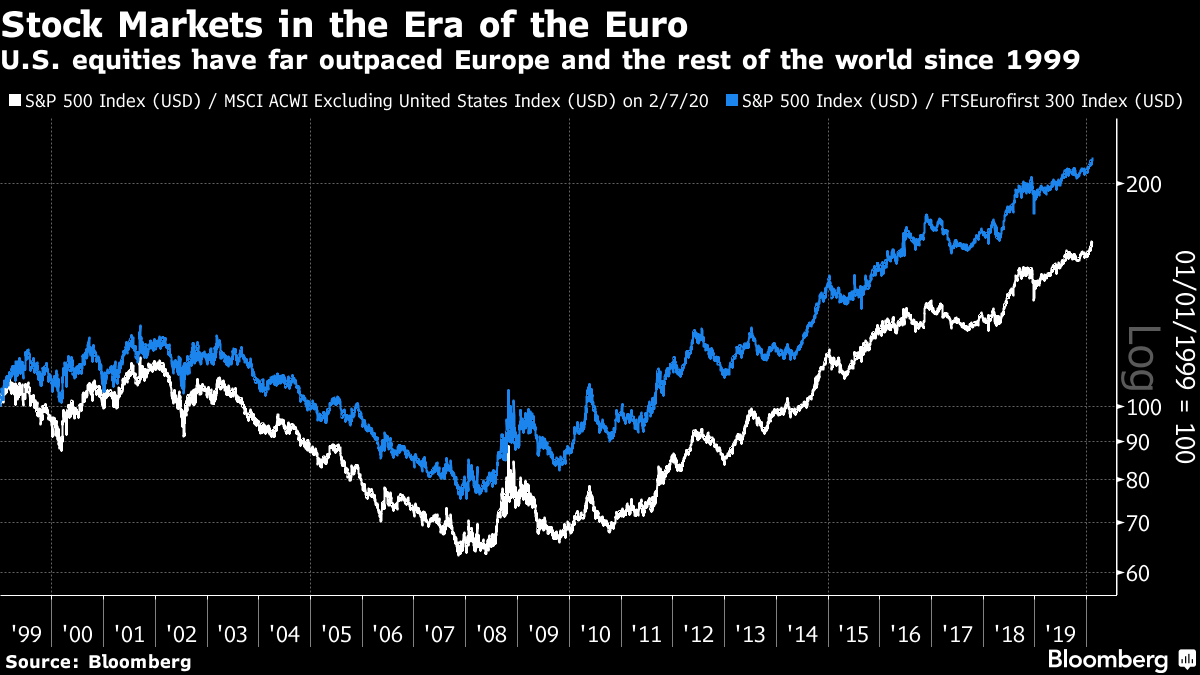

Twilight of the Euro 2020 was supposed to be the year when Europe began to shine. After suffering the decision by the U.K. to leave, the European Union had the chance to move forward with greater certainty. The easing of the U.S.-China trade war would aid recovery after a slump in manufacturing that appeared to be ending. And the euro could start to strengthen against the dollar, in a consummation devoutly wished in the capitals of Europe and the U.S. It hasn't worked out that way. After an ugly day's trading on Monday, the euro is at its weakest in four months, close to setting a 30-month low, and once more below its level on the day of the U.S. election in November 2016. One again the euro is falling down.  What exactly is going on? There is no one single factor behind the decline, but rather an overwhelming combination of circumstances that is pushing the currency lower. First of all, of course, there is politics. Across Europe, the center cannot hold. In Germany, the dispute over whether to allow the right-wing Alternative for Germany to take any part in the Thuringian state government led over the weekend to the resignation of Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, leader of the center-right Christian Democratic Union and Angela Merkel's chosen successor as chancellor. German politics is thereby thrown into chaos. In Ireland, the emergence of the radical and left-wing Sinn Fein in the country's general election as the largest party in its lower house has similarly left the established parties of center-left and center-right in a state of confusion. Irish politics have also been realigned, and it isn't clear what kind of policies or approach to government will emerge. Then there is the manufacturing sector. On Monday, Italy followed Germany and France in reporting dreadful industrial production figures for the end of last year. The coronavirus had had no effect at this point; manufacturing was supposedly picking up again and awaiting a boost from renewed Chinese post-trade war demand. We now see that all of the eurozone's biggest three economies ended the year slowing sharply.  This is bad because, thirdly, the eurozone is these days no place to take shelter from trouble in the Chinese economy. A slowdown of some dimension for China can now be taken as a given, just as a result of the belated measures to contain the epidemic. Sadly for Europe, this will come as Germany had put itself at China's economic mercy. Data from the International Monetary Fund show that exports from Germany to China now slightly exceed those from the U.S., a much larger economy.  If you want a haven from China, then, it is certainly not the euro. And it is probably the dollar. This chart from John Velis of Bank of New York Mellon Corp. shows that even though the U.S. has been the international aggressor in taking on China's trade power, it stands to lose the least from that economy's current difficulties. It is the obvious haven:  Beyond these fundamental reasons, there is also the technical issue that the euro has become a highly attractive currency for funding carry trades — the practice of borrowing in a currency with low interest rates, parking in one with higher rates and pocketing the difference, or "carry." Traditionally, carry trades have been almost synonymous with the Japanese yen, which was used as the funding currency for many bets that went disastrously wrong during the global financial crisis. But now the euro, with its negative rates, works even better. Over the last five year it has been a far more profitable funding currency for those wanting to park in Mexican pesos, for example, than the yen:  When a currency becomes popular for funding carry trades, it naturally comes under downward pressure. That is contributing to the euro's problems. Even taking all of this into account, however, it is clear that the dollar seems mighty attractive to foreign exchange traders at present. To show this, look at the following chart, which shows the gap between 10-year bond yields in the U.S. and Germany. This should be a critical driver of an exchange rate, with funds attracted to the higher rate. As the differential reduces, we would expect the currency with the higher rates to weaken. But as the chart shows, the differential has been narrowing in the euro's favor, very consistently, since late in 2018. And it hasn't helped. The Federal Reserve is now expected to cut target rates at least once this year with a 50-50 chance of a second reduction, according to fed funds futures, while the European Central Bank stands still. And that also makes no difference. Dollar strength runs directly counter to the pressures emanating from bond markets:  So why is money running toward the U.S., despite everything? Without wishing to pile on to any political triumphalism, the markets are obviously partial to the current situation, where Senator Bernie Sanders is seen as likely to be nominated for president by the Democrats, and also likely to lose to Donald Trump. There is also some triumphalism around U.S. companies. The biggest companies in the world, at present, are all American, and they are busily conquering the rest of the planet. U.S. internet groups' dominance has helped to ensure that the U.S. stock market continues to outperform the rest of the world, and particularly Europe, to a remarkable extent. The chart shows the relative performance of U.S. stocks since the beginning of 1999, when the euro came into being.  When capital flows into corporate America like this, plainly it strengthens the dollar. On a trade-weighted basis, the dollar just enjoyed its strongest week in almost a year. This does look a little like triumphalism. As Marc Chandler of Bannockburn Global Forex in New York puts it, the coronavirus is now widely interpreted as the moment that revealed China isn't, in fact, ready to challenge American economic hegemony, while there is also excitement at the notion that the botched handling of the situation in Wuhan could yet signal major trouble for China's political model. Couple that with a sense that Europe, whose common currency was intended two decades ago to launch another challenge to American exorbitant privilege, is also now revealing a deeply flawed political model, to go with a structurally challenged economy, and you have what could be a moment of classic market revulsion for Europe, combined with American triumph, and a very strong dollar. Could the triumphalism be premature? Of course it could. America's own political system is being bent in a number of different shapes, and we have nine more months of classic U.S. political soap opera to look forward to until the election. It is very possible that someone other than Donald Trump will be president at the end of it; conceivably someone who calls themselves a socialist. But for now, this is a moment of American triumph and European defeat, and it shows up clearly in the zero-sum game of the foreign exchange market. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

|

Post a Comment