| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter wondering when the Federal Reserve will acknowledge that there's already been a material change to the outlook. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter and Tracy Alloway, Executive Editor Yet to Turn The divergence between the Federal Reserve's words and the market's actions has gapped wider. The worst weekly equity rout since 2008 has prompted traders to price in a near lock on a March interest-rate reduction, with the odds topping more than 96% at one point on Thursday. Yet Fedspeak during the week betrayed little sense of alarm, or change in circumstances: Richard Clarida: "monetary policy is in a good place" and "it is still too soon to even speculate" about the impact of the coronavirus on the outlook for U.S. activity. Loretta Mester: "monetary policy is well calibrated to support our dual mandate goals, and a patient approach to policy changes is appropriate unless there is a material change to the outlook" Charles Evans: "It would be premature, until we have more data and have an idea of what the forecast is, to think about monetary policy action" Former officials are divided on whether the central bank should act or wait. The case for inaction is forcefully articulated by Tom Porcelli at RBC Capital Markets: "The markets are calling for policy prescriptions that address demand shocks to solve what is a potential transitory supply shock driven by pandemic fears. Even if it gets worse, unless you all of a sudden think we are looking at a 1918 Spanish Flu-like event, this too shall pass, folks."

"Cutting now when Fed funds is already sitting 100 basis points below neutral further cements the dangerous precedent already set that the only independent variable in the policy reaction function that matters is what the S&P 500 is doing of late." The counter-argument is that even if all Fed rate cuts could do is help put something resembling a floor under an equity market failing to respect so-called support levels, that could still be help worth having. The central bank's policy works by influencing financial conditions, of which the stock market forms a major part. Since one of the primary channels through which the coronavirus could affect the U.S. economy is public confidence (and in turn, consumption), the stock market's typically strong connection with measures of sentiment would argue for an aggressive approach aimed at shoring up both.

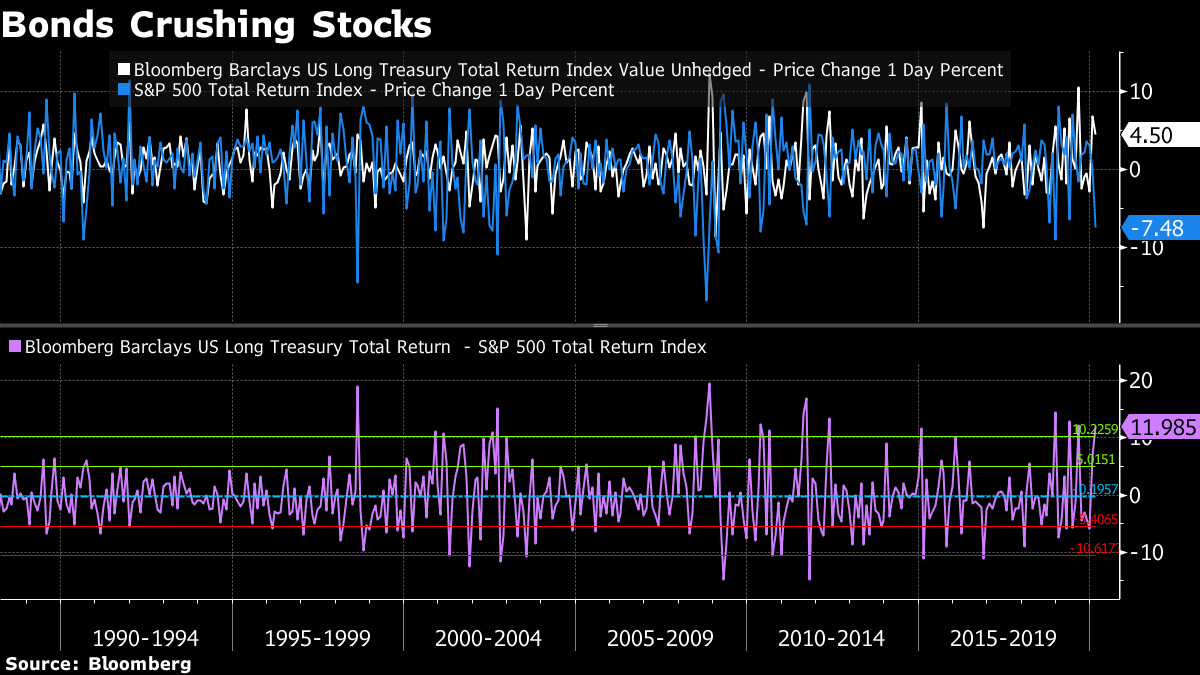

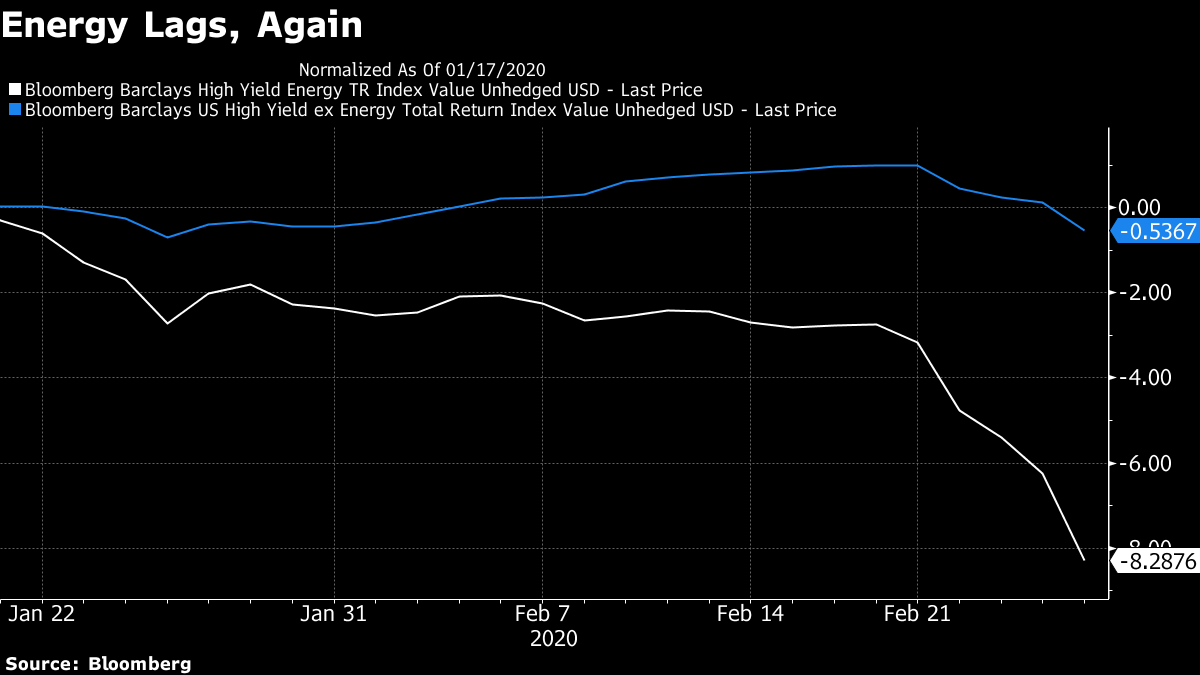

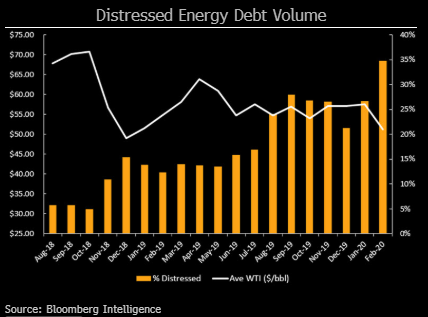

History shows a severe stock swoon in itself can constitute a material change to the outlook, regardless of the trigger. Hedge fund legend George Soros famously made the argument for reflexivity: that market participants can bring about the economic outcomes that they price in. Analysis of the repricing in the front end of the curve suggests that the Fed will cut rates in March or April, if policy makers keep with precedent that's held since the 1980s. The Fed isn't alone in its seeming reluctance to take rates lower in response to the coronavirus despite the wishes of the markets. President Christine Lagarde doesn't see a need for the European Central Bank to do anything yet. The Bank of Korea also didn't cut rates in its Thursday decision, electing to deliver targeted loan support for affected firms. The longer that central bank communications fail to express a willingness to act proactively to prevent a material shock to demand, the greater the likelihood such a shock materializes. That could be the case even if – once again – a muscular fiscal policy response would be most effective in mitigating both risks to public health and activity. Early 2019 offers a playbook for today. The market's looking for action, but words would be a start. There's plenty of opportunity, with over a dozen speaking appearances from Fed regional presidents and governors before the traditional communications-blackout period ahead of the March 17-18 policy meeting. In the short term, the equity market faces a head-on collision between a desire to avoid having to hold risk over the weekend and one of the best months for long bonds relative to stocks on record. The former would argue for another messy session on Friday, the latter would suggest rebalancing could buoy risk assets on the final trading day of the month.  BB-ware The price of credit means nothing if the access to it is curtailed. So even with investment-grade and high-yield borrowing costs still close to record low levels, the lack of new issuance in the credit markets (ex-China!) should send something of a shiver down investors' spines. Once again, energy-sector bonds are bearing the brunt of the damage in high yield in the U.S., where the HYG ETF suffered massive outflows.  It seems like just yesterday when this newsletter flagged worries about borrowing-base re-determinations putting the squeeze on energy companies – but that biannual bugbear is around the corner again. Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Spencer Cutter highlights that the share of junk energy bonds trading at distressed prices surged to 35% as of Tuesday, the highest proportion since 2016.  Bloomberg Intelligence Bloomberg Intelligence The 2015-16 experience showed it took a while for lenders to cut back, but when they did, it was a key contributor to corporate closures. "The vast majority of energy-sector bankruptcy filing in the previous downturn occurred around the spring 2016 borrowing-base redetermination process," adds Cutter. The more pervasive worry for the junk space may be the speed at which short-term spreads are being repriced. This newsletter highlighted in January that one of the top charts to watch in 2020 was the gap between short-term borrowing costs for the most creditworthy junk-rated firms compared with those of the U.S. government. As highlighted then, this is where concerns about an imminent downturn should become manifest. All of a sudden, vigilance on this front is now warranted. While still low by historical standards, BB two-year spreads have widened by more than 80 basis points over the past nine sessions, the briskest such blowout since early 2010. The rate of change may be more important than the outright levels in ascertaining how concerned investors are at present, and how the marginal borrower might be affected as a result.  |

Post a Comment