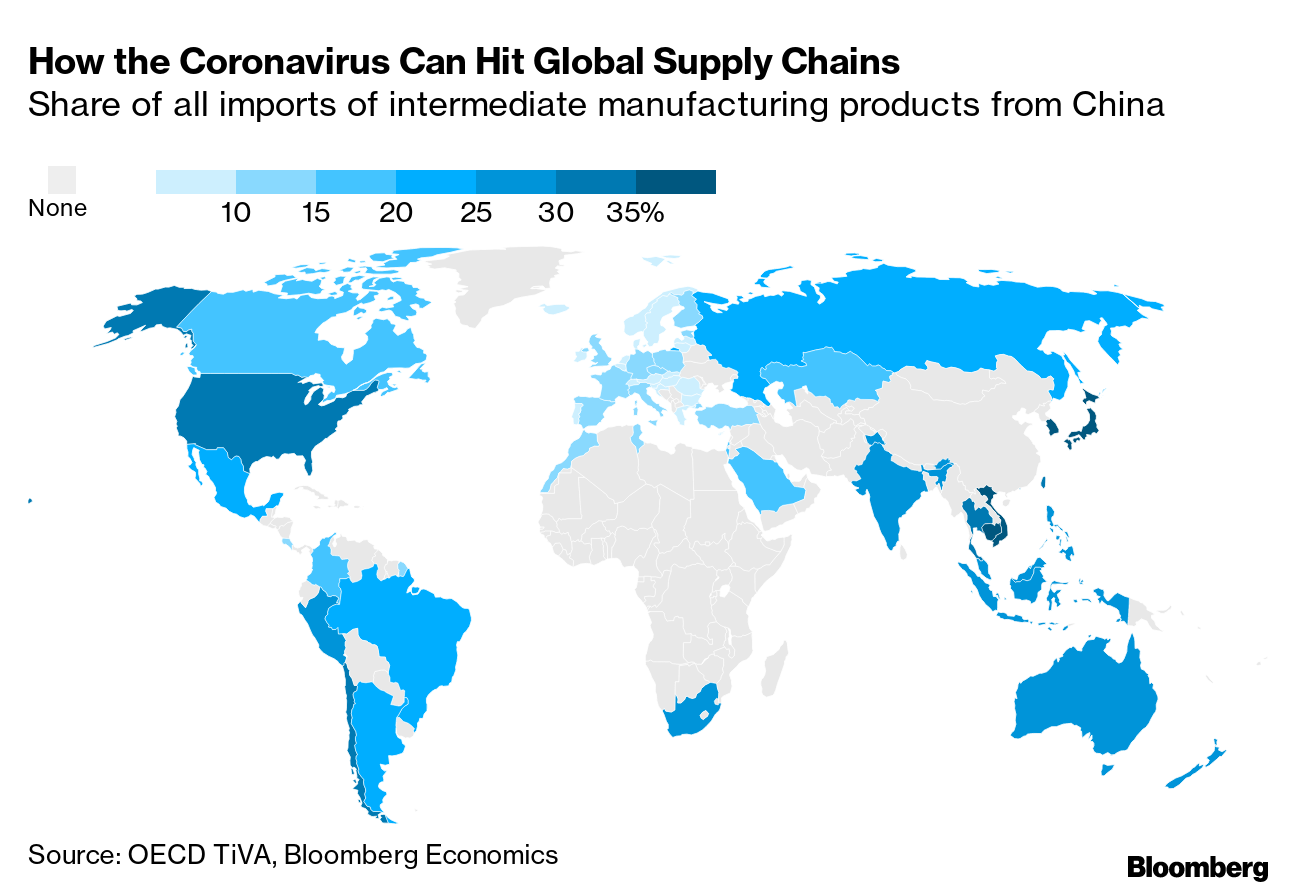

| In its heyday back in the 19th century, Lowell, Mass., proudly bore the nickname "Spindle City," a nod to the clattering textile mills that triggered America's industrial revolution. Nearby towns had their own claims to fame: Leominster was "Plastics City," Gardner was "Chair City," Holyoke was "Paper City," and Waterbury, Conn., was known as "Brass City." After World War II, some of these industries migrated to southern states before eventually moving offshore to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. In the end, they all congregated in one place: the Chinese seaboard, the workshop of the world. The coronavirus that's shuttered factories there, however, signals a new phase in what's becoming a great reversal of the west-to-east industrial journey. Businesses are reassessing China's role in global supply chains, and by the time this virus burns out, many of them will have started planning to relocate at least some of their production elsewhere. Deglobalization is accelerating. This week in the New Economy  Of course, traditional industries have been exiting China for years due to rising labor costs and environmental regulation, shifting to places like Vietnam and Bangladesh. But this trend is all part of globalization's natural churn. The same economic forces that emptied out New England in the last century are dramatically shrinking the city of Dongguan, in Guangdong province, where so much of U.S. manufacturing ended up. The coronavirus, though, calls into question the premises that underpin globalization itself. Deglobalization is driven by the discomfiting realization that the entire system now has a single point of failure—China. A cascading series of profit warnings dramatizes that point. Globalization was all about price and manufacturing efficiency, regardless of place, and its mutual dependencies were supposed to guarantee its stability. The U.S. and Chinese economies were bound together by the supply chains on which they both relied. But it turns out that place matters a great deal—for individual businesses, for entire industries and for the global economy. The epidemic that began in Wuhan has blocked key arteries of international trade. Now the global economy is having a seizure.  Increasingly, mutual dependency is becoming a source of fear, according to the Economist. The Pentagon and European defense officials, for example, are fretting about the national security implications of China's dominance in the active pharmaceutical ingredient sector. As the magazine notes, building new factories elsewhere to ensure the supply of ingredients for essential medicines would be relatively straightforward, but it would "involve upending well-established political and economic theories, starting with the wisdom of allowing private companies to seek out the best-value goods, with little heed paid to their origin." Jörg Wuttke, chairman of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, expresses the argument bluntly: "The globalization of putting everything where production is the most efficient—that is over." In some ways, China set itself up for this reversal by weaponizing trade. Japan has never forgotten the lessons of 2010 when China choked off supplies of rare earths critical to the electronics industry during a standoff over a set of disputed islands.  Now, Chinese President Xi Jinping (above) is conducting the equivalent of industrial triage, desperately trying to restart factories most critical to global supply chains. But as Mikko Huotari, the director of the German think tank MERICS argues, this isn't so much comforting as a sign of the scale of the problem. "China will be a different country after the coronavirus crisis," he says. "China's reputation for reliability is in tatters, and momentum for supply-chain diversification inside and outside the country is growing." Chinese industrial planners understand better than anybody the fragility of global supply chains. If they unravel, it will happen suddenly warns Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tyler Cowen. This is because "each part of the chain relies upon other parts to add its value," he says. For the first time since World War II, "the global economy faces the possibility of a true decoupling of many trade connections." China was the biggest winner from globalization, which of course means it will be the greatest loser from deglobalization. In a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Singapore, 28% of those polled said they are setting up, or using, alternative supply chains to reduce their dependence on China. Tens of millions of jobs in China are threatened. Ultimately, social and political stability will be at stake. ________________________________________________

Like Turning Points? Subscribe to Bloomberg All Access and get much, much more. You'll receive our unmatched global news coverage and two in-depth daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. Bloomberg's Green Daily is where climate science meets the future of energy, technology and finance. Sign up for our daily newsletter to get the smartest takes from our team of 10 climate columnists. Sign up here . Download the Bloomberg app: It's available for iOS and Android. Before it's here, it's on the Bloomberg Terminal. Find out more about how the Terminal delivers information and analysis that financial professionals can't find anywhere else. Learn more. |

Post a Comment