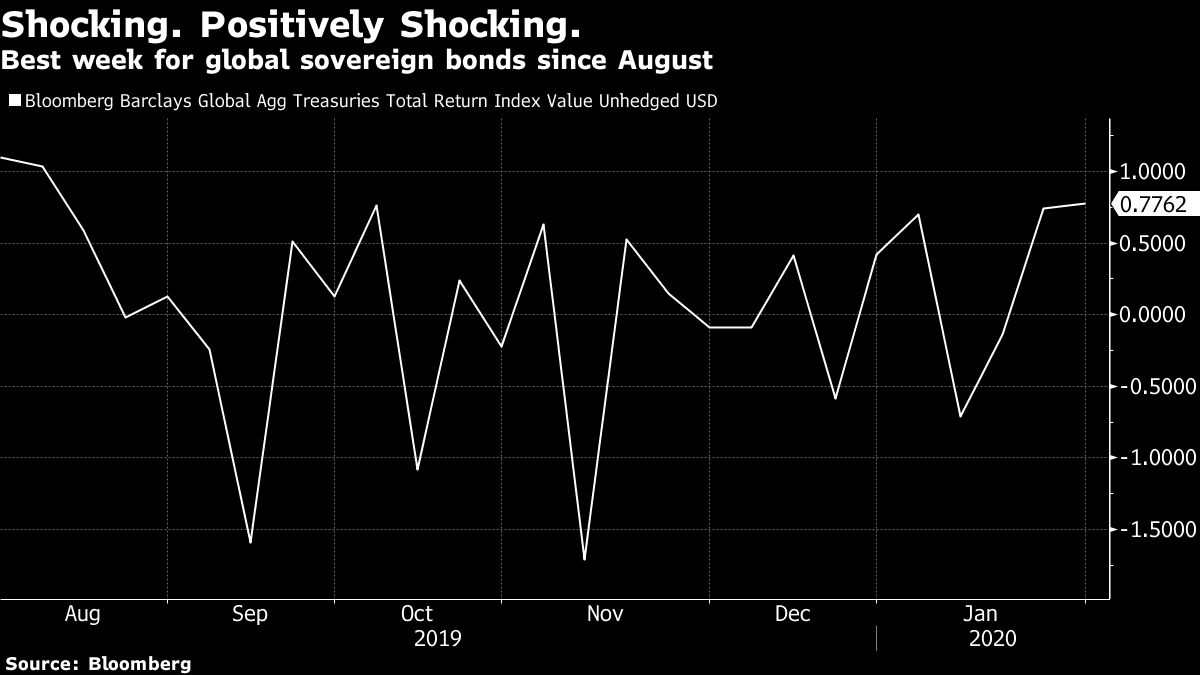

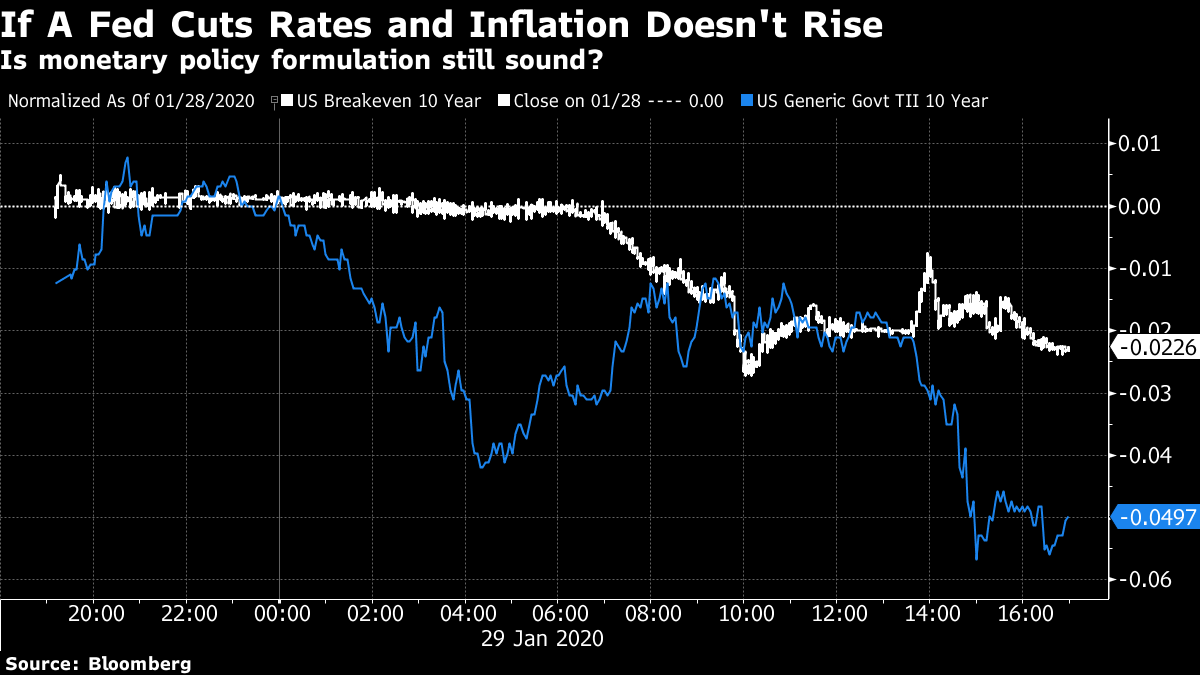

| come to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that was told it was the 10-year yield, not the 30-year, that was supposed to revisit 2% in 2020. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter August All Over Again The incredible Treasury rally extended to new extremes this week. A mild degree of risk-off to end last week crescendoed. That, coupled with a purportedly uber-dovish Federal Reserve, saw the 10-year yield sink to as low as 1.53%. Global sovereign bonds are on track for their best weekly return since August.  On Monday, the 10-year U.S. yield closed nearly three standard deviations below its one-month average, putting the briskness of the decline nearly on par with last August, when a combination of fears of a Fed behind the curve on easing and an escalating trade war amid a deteriorating global backdrop brought U.S. recession fears to the fore.  Market participants may doubt the Treasury rally, but few are willing to swim against a current that's akin to a tidal wave. All the same, just as was the case last week, the justification for the bond bid has little to do with the published economic data, but rather how bad the effect of the coronavirus could be – along with other drivers. Strategists are pointing to a variety of extenuating circumstances for the magnitude of this run that go beyond the epidemic's impact on growth. Positioning may be a cause of the acute rally in 10-year notes, given "the possibility that a bull flattener is the pain trade of the moment, as the bear steepener crowd has faced diminishing conviction since January 1," writes Ian Lyngen at BMO Capital Markets. "Second, due to the scale of the drop in rate, an element of convexity hedging is likely at play." Economic data haven't been bad. Preliminary manufacturing PMIs for Germany, France, and the Eurozone released last week exceeded expectations. U.S. data this week included a massive beat on the Richmond PMI (which bodes well for next week's ISM Manufacturing report), buoyant readings of Conference Board and Bloomberg consumer confidence readings, and a fourth-quarter GDP print mostly in line with expectations (albeit while indicating meager price pressures). Thursday's session may have offered some support for those who think the Treasury fever is due to break imminently. The 10-year yield set fresh 2020 lows before erasing all of the move after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus to be a global health emergency (which will boost the responsiveness of aid to stop its spread) and declined to issue a travel ban. As for the re-inversion of the three-month, 10-year Treasury curve via bull-flattening, this is unlikely to be an indicator of anything in store for the U.S. economy, based on analysis cited repeatedy in last year's newsletters. Near, Far, Wherever You Are They said it would be a nothing-burger of a Fed decision. They were wrong. Market participants saw meaning in a handful of words being changed in the central bank's January statement. Fed Chair Jerome Powell faced numerous questions on the intention of the statement now saying that the policy stance was appropriate to get "inflation returning to" the 2% target, rather than "near" that pace. The context is important: the Fed is in the process of conducting a review of its framework, which may or may not explicitly involve a shift towards make-up strategies for a shortfall in inflation. The chairman didn't tip his hand decisively on this matter. The shift in the statement was because policy makers "wanted to underscore our commitment to 2% not being a ceiling," he said. Powell later added that "under our existing framework, we've been able to succeed or get close to succeeding," while "we do struggle, as other central banks do, with the inflation goal." Nonetheless, his initial comments were sufficient to spur a big rally in bonds. Powell's remarks were seen as changing the Fed's likely rate trajectory over time, but not inflationary outcomes. Hence, a crash in real yields and muted activity in breakevens during the press briefing.  There's a much more benign explanation for what transpired. December's minutes marked the first time that officials documented unease about the description of "near" 2%, suggesting it could be misinterpreted as having comfort with inflation running below that level and preferred language suggesting inflation returning to the 2% objective. Which…is exactly the language that was inserted into the January statement. It's definitely a nod to the doves (if concern about symmetric inflation outcomes should be characterized as dovish rather than normal given the central bank's mandate). Whether it's one that will be reflected in an overhaul of the Fed's framework that warrants an immediate change to interest rates remains an open question. But Wall Street's shifting that way. The introduction of a cut solely for inflation make-up purposes – even without a threat to real growth – introduces somewhat of a new skew into the Fed pricing calculus. Neil Dutta, Renaissance Macro Research's head of U.S. economics, wrote that the central bank was "setting the stage for some type of inflation make-up strategy. Dovish." "The expected shift in framework, and hence shift in optimal policy setting, is part of the reason we continue to look for an easing announced alongside the change in framework in June," writes JPMorgan's Michael Feroli. The spread between May and August federal funds futures, at -12.5 basis points, is now basically a coin flip on a cut around the time the Fed's framework review will be concluded.  Meantime, the 10-year Treasury 10-year forward rate is well below the median-long run dot, and the cash rate is below not only both of those but also expectations of what the fed funds rate will average over the next 10 years.

This all serves as a fairly hefty cap on the downside for bonds in the event they should ever make an about-face. In fact, the current level of 10-year rates reflects a certain (increasing) amount of concern that the Fed will be forced to return policy rates back to zero.  |

Post a Comment