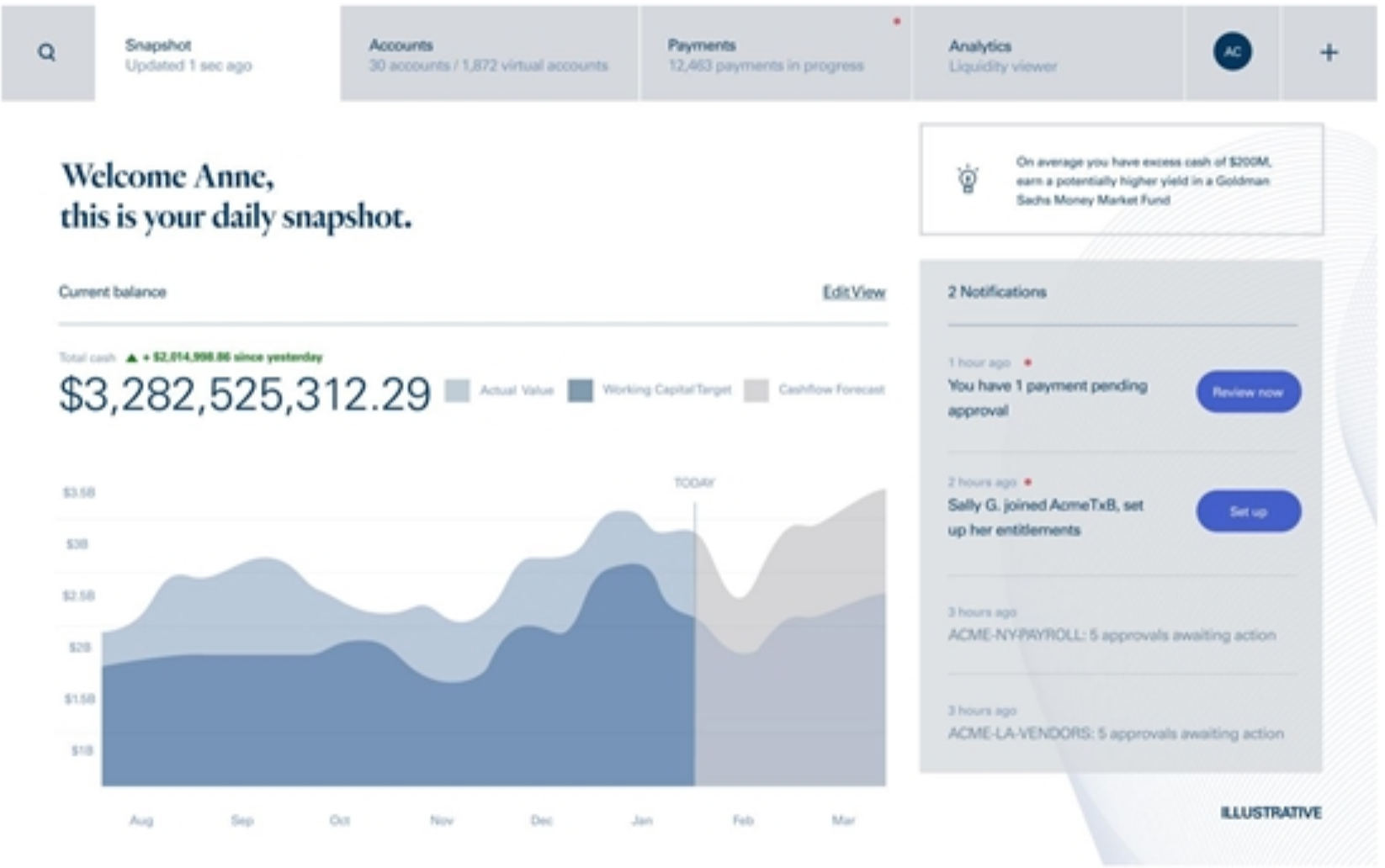

Transaction banking One thing you could do if you're a big bank is, like, companies give you their money, and you hold on to it for them, and you give them a website where they can log in and see how much money they have, and when they need to pay their workers or suppliers or whatever, they tell you to do it and you send the money. This is, roughly, called "transaction banking." It's pretty standard? There are ways to innovate in this business, or make it more complicated (you can pay their foreign suppliers in foreign currency, you can automatically advance them some money to pay suppliers even if they don't have it yet, you can make the website better), and of course there are ways to make it risky (you take their money and invest it in Bitcoin or Ponzi schemes, or steal it), but the basic idea would be familiar to medieval bankers. They give you money, you hold it for them, you give it back when they need it. Obviously it is a big business because there are lots of companies and they have lots of money and they have to pay lots of employees and suppliers and so forth. Many other banking businesses are lumpy and unpredictable and specialized: Most years, most companies won't need to take out a syndicated loan or issue bonds or raise equity or do a merger, and they almost never need to do complex derivatives. But every company needs a checking account every day. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. is holding its first investor day today. (Disclosure, I used to work at Goldman, selling complex derivatives to corporate clients who almost never wanted them, oops.) Here is the presentation. It is long and about a lot of things, but there is a slide (slide 16 of the first presentation) listing "four areas of focus." They are "transaction banking," "third party alternatives," "digital consumer bank" and "wealth management." These are all, as, like, the history of Goldman Sachs goes, pretty boring, but transaction banking is somehow both the most boring and the one they might be most excited about. Later (slide 15 of the fourth presentation, on investment banking) Goldman points out that this is a big business ("Attractive Addressable Market" with "$5tn US Corporate Deposits"), so "Small Market Share Can Generate Meaningful Economics." Also it provides "Stable, More-Durable Revenues," "Expense Savings" and "Funding Diversification," and is "Synergistic with Broader Strategy." They like it. But then the slide gets to the "Strong Client Value Proposition" and it's like "fast and easy onboarding" and "modern tools and simple processes." The pitch here is that Goldman will compete effectively to manage companies' cash for them because it will build a good website. In fact the next slide (slide 16) is a picture of that website. "Welcome Anne, this is your daily snapshot," it says. Anne has $3.28 billion in the bank, good for her:  Source: Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Source: Goldman Sachs Group Inc. There's a lightbulb over on the right suggesting that that number might be a little high, and that she should consider moving some of it to a Goldman Sachs money market fund. "Synergistic with Broader Strategy"! It feels a little like, having rolled out a simple user-friendly consumer banking website to offer people savings accounts, they were like "well we have this website, might as well use it to offer companies checking accounts." One way to interpret this is that Goldman has embarked on a quest to be boring. This interpretation seems plainly correct. The old Goldman approach—making a lot of money on lumpy investment-banking fees, risky balance-sheet-intensive trading, and both-lumpy-and-risky principal investing—is disfavored in modern banking. It is disfavored by regulation (the Volcker Rule, capital requirements) and by market conditions, but it is also particularly disfavored by Goldman's own investors, who want reliable recurring revenues. Also it is just, in the scheme of things, sort of niche. You can only get so big by advising on mergers and trading derivatives for hedge funds. You can get plenty rich that way—your revenues per employee can be high—but if you want to be a giant bank you need to find ways to touch everyone's money, every day. Consumer banking. Transaction banking. Wealth management. "The PE firms are the new Goldman Sachs," an investor told the Financial Times, while "Goldman Sachs is trying to be JPMorgan." JPMorgan is really big! The path to bigness is not in specialized high-value-add niche financial services. The path to bigness is, like, everyone gives you their money and you hang on to it for them etc. In different ways, Goldman is moving into relatively mass-market businesses, which are also relatively boring businesses. The way you win is not by brilliantly structuring complicated trades or by having nerves of steel to manage complex risks, but by having a fast and easy onboarding process and a nice website. I talk sometimes around here about post-financial-crisis regulation as an attempt to change the culture of banking. Banning proprietary trading is not specifically about the financial risk of prop trading; it's about getting people who like taking proprietary risk out of positions of power at big banks. One obvious interpretation here is that this attempt worked, amazingly well, and now Goldman has pivoted from taking complex proprietary risks to designing user-friendly websites. (The fact that Goldman is in the early years of management by David Solomon, who came from investment banking, and who replaced Lloyd Blankfein, who came from sales and trading, is also a good place to look to explain the cultural shift.) Again: This interpretation seems correct. But I want to mention another interpretation. It goes something like this. Goldman is, in this theory, an incorrigible generator of financial interestingness. It hires smart people who share a certain adventurousness about risk and financial structuring. They like to do weird stuff. Compared to other big banks, they have traditionally funded their weird stuff disproportionately by appealing to funding sources who like weird stuff. "Buy Goldman stocks or bonds or structured notes, we are weird, it will be fun," was the implicit message, while other banks' message is more like "buy our certificates of deposit, we are boring, it will be boring." If you open a derivative position with Goldman, you will have a little adventure; if you open a transaction account with Bank of America, you will not; Goldman funded relatively more of its business with derivatives and less with transaction accounts. There was a rough, natural segregation. Goldman had more fun with its money, and it funded itself relatively more with fun-seeking money; other banks had less fun, and funded themselves with more boring money. The boring money is cheaper. Now Goldman is wholeheartedly embracing boring money. Another slide (slide 8 of the investment-banking presentation) talks about "Embracing the Bank Model." "Significant Asset Growth Opportunity," it notes, since about 25% of Goldman's assets are in bank entities, compared to a 65% peer average. If you're a normal bank holding company, you keep most of your assets at your regulated bank entity, and you fund them with cheap deposits. If you're Goldman, you keep most of your assets out of your bank, and you fund them with bonds and repo lending. The plan is to change that, to move Goldman's assets into the bank. "Increased Utilization of Bank Entities," says the slide. "Continue migration of businesses into bank entities." "Capture lower cost funding." The natural and surely correct cultural impact of this is that Goldman will get more boring money and do more boring things with it. But you could imagine little areas of pushback. You could imagine some Goldman structurer who is used to taking money from adventurous hedge funds and doing adventurous things with it, and who one day notices that Goldman has taken $3.28 billion from Anne, in her corporate transaction account, and just parked it in fed funds or whatever. Why not do adventurous things with Anne's money? Why not, you know, build weird derivatives with it or whatever? Sprinkle in a little tax structuring. Invest it in credit index tranches, or Bitcoin. Sure Anne isn't adventurous—she's just here for the nice website—and sure there are lots of regulatory and supervisory constraints on what banks can do with their transaction-account clients' money. But there is some room within those constraints to be more or less aggressive, more or less interesting, and your legacy culture may determine which way you go. In other words, building up a lot of boring mass-market businesses around the core of Goldman Sachs will probably—surely—have the cultural effect of making Goldman's culture more boring and mass-market, stable and safer. But it might also have the cultural effect of importing some of Goldman's more adventurous approach into those boring and mass-market businesses and making them a bit more exciting, riskier, lumpier, more aggressive. The influence might go both ways; bringing boring banking to Goldman might also mean bringing some Goldman to boring banking. Optional early redemption The way bonds basically work is that they have a maturity, 10 years or whatever, and they get paid back at maturity, and if the company issuing the bonds wants to pay them back early, or the investors buying the bonds want to get their money back early, they are out of luck. The deal is 10 years (or whatever), and after the bonds are issued neither side gets to change the deal. Usually, at any point in time, one side will be happier with the deal than the other: If interest rates go up, the price of the bonds will go down and investors will wish they had kept their money; if interest rates go down, the price of the bonds will go up and the company will wish it had waited to issue bonds. But that's life. There are exceptions. If certain things go wrong for the company, or if it does certain bad things—misses an interest payment, violates a covenant, defaults on other debt, etc.—the investors can demand their money back right away. The company violated the deal, the deal is over, the investors get their money back, generally at 100 cents on the dollar. Essentially every bond has a feature like this (you call it "acceleration upon default," or sometimes, loosely, an "investor put"); it's the basic way that the deal is enforced. Investors lend the company money for a time, but if it doesn't live up to its obligations they get their money back. Some, though not all, bonds have another provision, allowing the company to pay them back early at its own option. ("Optional early redemption," or more commonly an "issuer call right.") Sometimes it can do this at 100 cents on the dollar, after a certain amount of time has gone by, but often it has to pay the bonds back at a premium. The bond matures in 10 years at 100 cents on the dollar, but the issuer can call it after 5 years for 120 cents on the dollar, or whatever.[1] There is a small theoretical opportunity for mischief here. A company has bonds outstanding. It doesn't want to have those bonds outstanding: It finds their covenants onerous, or interest rates have gone down and it would rather pay a lower interest rate. It can call the bonds, using the optional early redemption provision, but then it will have to pay 120 cents on the dollar. What if, instead, it tried to get investors to put the bonds at par? It could violate a covenant or miss an interest payment; the investors would all say "ah this bond is bad, but now we have a put right" and demand that the company buy their bonds back at par. The company would happily do it and end up buying back the bonds at 100 rather than 120. This is not actually an especially practical worry because, in the real world, it is mostly quite bad for companies to have investors accelerate their bonds. It triggers defaults on other debt, it lowers your credit rating, it is generally a bad bankruptcy-esque credit event that imposes very real costs on your ability to stay in business. Companies don't go around casually defaulting on their bonds to dare investors to demand their money back. This is (mostly) not a thing. But sometimes companies do default on their debt—not casually, often because things are bad—and investors demand their money back, and they make an argument something like the above. They say "well wait this company chose to default on its debt instead of calling the bonds at 120, so it's cheating, so instead of just getting our money back at 100 cents on the dollar, we should actually get 120 cents on the dollar." And courts have sometimes agreed with them. Legally, it is a thing. The main case is called Cash America. We've talked about it a few times. It applies when a company "voluntarily" breaches a covenant; courts treat that as being like calling the bonds, and make the companies pay the makewhole. Here is a fascinating blog post from Mitu Gulati about Argentina. Argentina, incredibly, issued a 100-year bond less than three years ago, with a 7.125% coupon; now that bond is trading at about 45 cents on the dollar and the market worries about a near-term default. If it defaults, investors can demand their money back now, instead of at maturity in 2117, though of course they won't get it all; Argentina would negotiate some sort of compromise workout in which investors get some fraction of what they're owed, as it did the last time it defaulted, and the seven times before that. But the Argentine century bond also has an "optional early redemption" provision allowing Argentina to call it, early, at a premium. In my schematic description above I just pretended that the premium on early redemption would be paying 120 instead of 100, but in reality the way these premiums usually work is a "make-whole" formula that calculates the present value of the bond using some low discount rate. Argentina has a "T+50 make-whole," which is fairly common; if it calls the bonds it has to pay the present value of all of the future interest and principal payments, discounted at a rate equal to the comparable U.S. Treasury bond rate plus 0.5%.[2] The longest U.S. Treasury rate these days is about 2.07%; if you discount 97 years of 7.125% interest at 2.57% you get quite a large number. Specifically you get about 262 cents on the dollar.[3] So if Argentina voluntarily called these bonds it would have to pay 262 for them. They're trading at about 45. If investors get to accelerate the bonds—because Argentina misses an interest payment, etc.—then they can demand 100, though they won't get it; they'll get whatever negotiated haircut Argentina works out with them and its other bondholders. But what about that call right? Gulati writes: The implication of the foregoing, as the various law firm memos written in the wake of the Cash America case warn clients, was that bond issuers using the standard Optional Redemption provision (aka "make-whole" premium clause) should henceforth be forewarned that they might be liable for this payment if their triggering of an Event of Default sometime in the future were seen as "voluntary" by a court. ... But what about the sovereign context? After all, sovereigns cannot be forced into a bankruptcy proceeding (there is none). Further, given that sovereigns can in theory always tax their people more to repay their debt, sovereign debt restructurings are in a sense always "voluntary". (Worse, sovereigns themselves frequently describe their their debt restructurings as "voluntary" – see here and here). So, does the remedy given by the court in Cash America apply any time a sovereign (with an Optional Redemption provision) triggers an Event of Default along the way to seeking a "voluntary" debt reduction? Gulati doesn't really think this would happen, and I agree, but it's a worrying possibility. If a court decided—or if investors just assumed—that the century bonds have to get the makewhole, then that means that they should get paid off at 262. They wouldn't get that much in a restructuring, because no one would get the full amount of their claims. But if the century bondholders think that this interpretation is right, then they'd argue to get, say, twice as much as other bondholders in any restructuring. And that in turn would make any restructuring harder, both because the other bondholders would feel aggrieved but also specifically because the collective action clauses in Argentina's bonds—the clauses that are supposed to allow Argentina to restructure its debt without a decade of lawsuits—require that every series of debt be treated uniformly. It is all pretty hypothetical at this point, but it is a weird one. Flybor Last week we talked briefly about Skytra, a subsidiary of Airbus SE that will allow airlines and other customers to trade derivatives on airline-ticket-price indexes. I know what happens when companies trade derivatives on their own products! I wrote: I do not know how this "series of indexes that capture fare fluctuations across the industry" will be set, but after Libor and Chicken Libor, I tend to expect manipulation in any index of industry prices. Let's set a calendar reminder to meet back here in five years to discuss the scandal of airline ticket price index manipulation. "Flybor," I plan to call the resulting scandal. But that was perhaps unfair. I heard from Skytra's chief executive officer, Mark Howarth, who wrote: We share your concerns about benchmarks and the potential for manipulation. We wanted to highlight some of the things we've done with the Skytra Price Indices to make sure they are robust and useful. The indices only use actual transaction data, with real ticket prices. We're in the realm of billions of data points here. We measure moving averages across many airlines collectively. We're not measuring a single airline or route, and we model and watch for anomalous events via an extensive back history. We cater for events impacting prices like an airline suddenly suspending operations, and the same tools are designed to catch attempts to distort the data by submitting inaccurate prices. One thing to think here is that there are some companies that are in the business of building a product and setting prices, and there are other companies that are in the business of trading a commodity. If you let Apple trade derivatives on the price of the iPhone, it would have a huge advantage, because it more or less decides the price of the iPhone; that decision is constrained by economics—there is some profit-maximizing price—but is still its decision. If you let a big wheat farmer trade derivatives on the price of wheat, he would have a little advantage, because he produces a lot of wheat and knows if his crop will be big or small etc. But he doesn't set the price of wheat; the price of wheat is just a market price, and he takes it. Intuitively one thinks of airline ticket prices as being set by the airlines but I suppose the point is that, at a certain level of abstraction, they are commodities. Congrats, Nav Man, what an anticlimax: Navinder Singh Sarao, the British trader accused of contributing to the 2010 stock-market "flash crash," won't serve any more time in jail, a federal judge ruled Tuesday, capping a multiyear saga that gripped markets and traders after one of the most dramatic stock plunges in history. Mr. Sarao was sentenced to time served as well as a year of home confinement by Judge Virginia Kendall of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. He will be allowed to leave his house for medical appointments, work and church, among other preapproved reasons. I mean, I'm all for it; the original claims that Sarao caused the flash crash were overblown, he seems basically harmless enough, you shouldn't put people in prison for nonviolent first offenses unless you really need to, etc. Still it is pretty unusual for someone to (1) be blamed for a big high-profile economic disaster (albeit a short-lived and somewhat silly one), (2) plead guilty, and (3) get sent home with a warning not to do it again. Once you gear up the prosecutorial resources to blame him for the flash crash, and to extradite him from England to stand trial, it's weird for everyone to be like "oh never mind he's fine, carry on." Things happen Sixteen Leading Quants Imagine the Next Decade in Global Finance. Warren Buffett Throws in the Towel on His Newspaper Empire. JPMorgan Plans To Cut Hundreds of Jobs Across Consumer Division. Reviving research in the wake of MiFID II: Observations, issues and recommendations. Wall Street's London Outposts Are Braced for a Brexit Beating. Green-Bond Trading Is Going Electronic. Bitcoin Has Lost Steam But Criminals Still Love It. After WeWork, Real-Estate Startups Rethink Pursuit of Fast Growth. Yes, there really is an arugula shortage. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] The more common approach is not a fixed premium but T+50 discounting, which we'll get to. Also some other bonds have other, sort of intermediate early redemption provisions: The company can call them in the first few months at some modest premium, for instance, or there is a modest-premium put on a change of control, etc. [2] I know that there is not actually a 97-year Treasury but people make do with the 30. The provision is on page S-26 of the prospectus for Argentina's bond. [3] That's just taking the Bloomberg YAS yield and spread analyzer page for the Argentine century bond (ISIN US040114HN39), plugging in a 50bp spread, leaving other inputs the same, and reading out the price. You can get pretty close by saying "ehh 97 years is basically a perpetuity" and just dividing 7.125 by 2.57. |

Post a Comment