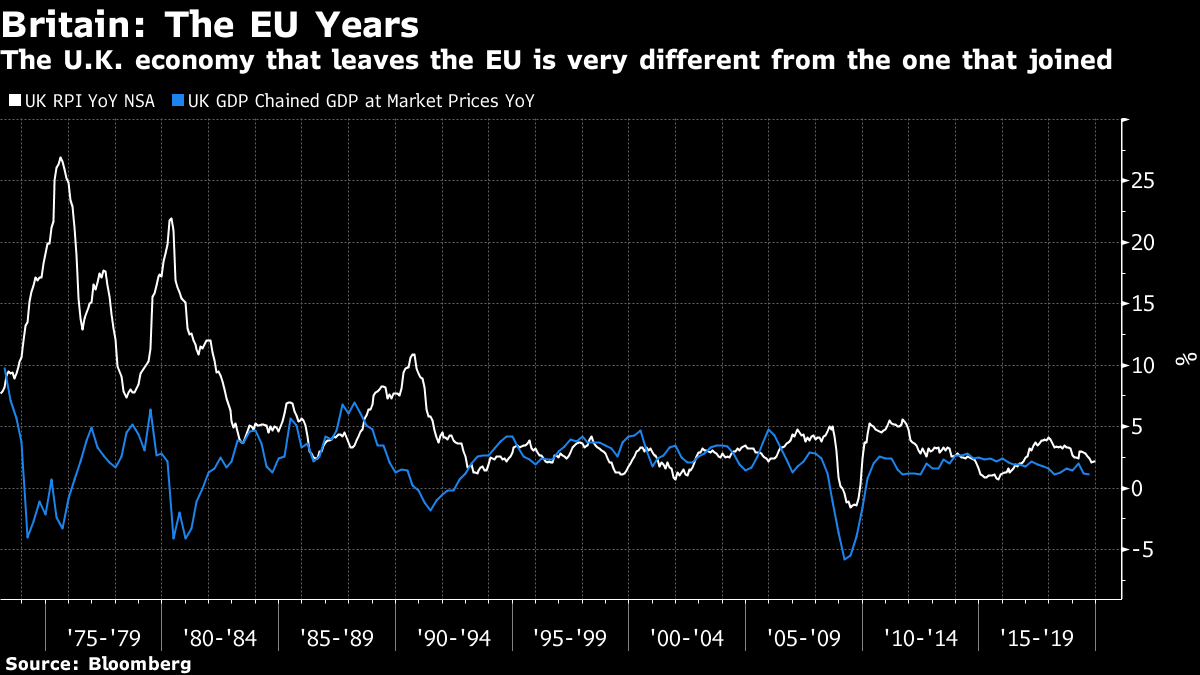

Coronabonds Making sense of the last few days in markets requires some of the skills of a doctor. The patient has some severe symptoms, some of which can plainly be attributed to a disease. But is some other medical condition also at work? It can be difficult to tell, particularly as doctors, like those who work in capital markets, don't have the ability to perform a controlled experiment. But we need to try. The bare facts of Thursday's trading are that bonds moved to some truly extreme positions implying a seriously negative outlook for the economy. The Treasury yield curve inverted again, including the three-month/10-year relationship that has proved the most reliable recession indicator in the past. Then it rebounded once more.  At the same time that the curve inverted the most and began to rebound, so 10-year real yields (obtained by subtracting the inflation breakeven for the same period) dropped to their lowest level since May 2013, finally taking out the low they hit during the wave of pessimism that followed the Brexit referendum in summer 2016:  The bond market is huge and liquid, and its judgments are generally meaningful. So to be clear, it gave an unambiguous warning signal of a recession, and at the same time made long-term money as cheap as it had been (in the terms that count most) since the era before the Federal Reserve had begun to unwind quantitative easing, and when the fed funds rate was still zero. Such signals from the bond market should never be taken lightly. What, then, to make of the fact that 10-year yields immediately started a recovery, and ended the day roughly where they had started? To explain the course of the day's events (although not how the bond market came so close to these extremes in the first place) we can attribute virtually everything to the continuing and terrifying spread of the novel coronavirus. The news during the day was troubling in the extreme — flights are being canceled, the number of confirmed cases is fast mounting, and it is evident that the outbreak is bound to cause at least some economic damage. Press commentary was also making clear that parallels with previous epidemics weren't necessarily useful for markets. That is partly because there is no previous example of an outbreak on this scale happening when markets seemed overextended. It is also because in all previous examples over the last 100 years or so, the "tail risk" that terrifies epidemiologists was avoided. We have no guarantee that the tail risk (an epidemic on the scale of the influenza at the end of World War I) won't come true this time, and no means of gauging what would happen to the economy if it did. Alarm manifested itself in a rush into bonds and falling yields. The bottom came the moment the headline hit screens that the World Health Organization had designated the outbreak an official global health emergency. The recovery started straight after, as the WHO went on to say that it saw no need for travel restrictions at this time. It had been reasonable to fear new restrictions, which would have inflicted further damage on the economy, so this was good news — and reason to push bond yields back up. This wasn't irrational, and was rather in line with the "random walk" theory of efficient markets (which holds most of the time), in which prices incorporate all known news and move randomly on one piece of new information to the next. Gathering bad news was reflected in gathering pessimism. The beginning of the WHO announcement was a further piece of bad news — until it improved. So Thursday's events are an example of the nasty uncertainty and volatility that is unavoidable until such a time as the virus outbreak comes under control. That doesn't mean that the messages of the bond market can be ignored altogether. Yields were already falling before the Wuhan virus began to hit the headlines last week. Economic growth numbers are nothing to be excited about. And concern about trade, in particular, is intense. The measures that have already been taken to control the virus ensure that trade will worsen before it improves. For just one illustration, here is how the S&P 500 airfreight sector has performed relative to the market as a whole over the last 10 years. Something worrying was happening to trade and economic activity before the virus outbreak, even if it wasn't enough to bring the bond market to quite such an extreme:  Auf Wiedersehen, Pets This is the last newsletter I will write as a citizen of the European Union. For some fellow Britons this is a matter of joy and liberation. I don't feel that way about it. Some hope that we will rejoin at some point. But that isn't realistic. The people have decided and the issue of membership is settled — even if many other issues about the U.K.'s relationship with the rest of the world, and with the continent 17 miles from its coast, remain to be decided. There is much more to the decision to leave the EU than economics. That is just as well, because the contemporary British economy is profoundly different and much stronger than on entry in 1973, when the U.K. was racked by industrial strife and stagflation. Now, there are many economic problems, and like much of the rest of the developed world the country suffers deepening inequality. But it is hard to see what the EU specifically has done to cause those problems, or what leaving will do to solve them. And while the EU shouldn't be given all the credit for the improvements in the U.K. economy since 1973, the tale of Britain's performance over those years suggests that EU membership cannot have done much harm.  Britain's indecision over the last four years has been a national embarrassment. But thankfully some of the wilder ideas of leaving the EU with no deal didn't come to fruition, and Brexit has, at the last, happened without causing any major dislocation to the world economy, or its markets. Now to try to make the new arrangement work. And if continental Europeans ever miss us, we will still (whether some of us like it or not) be only 17 miles away. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment