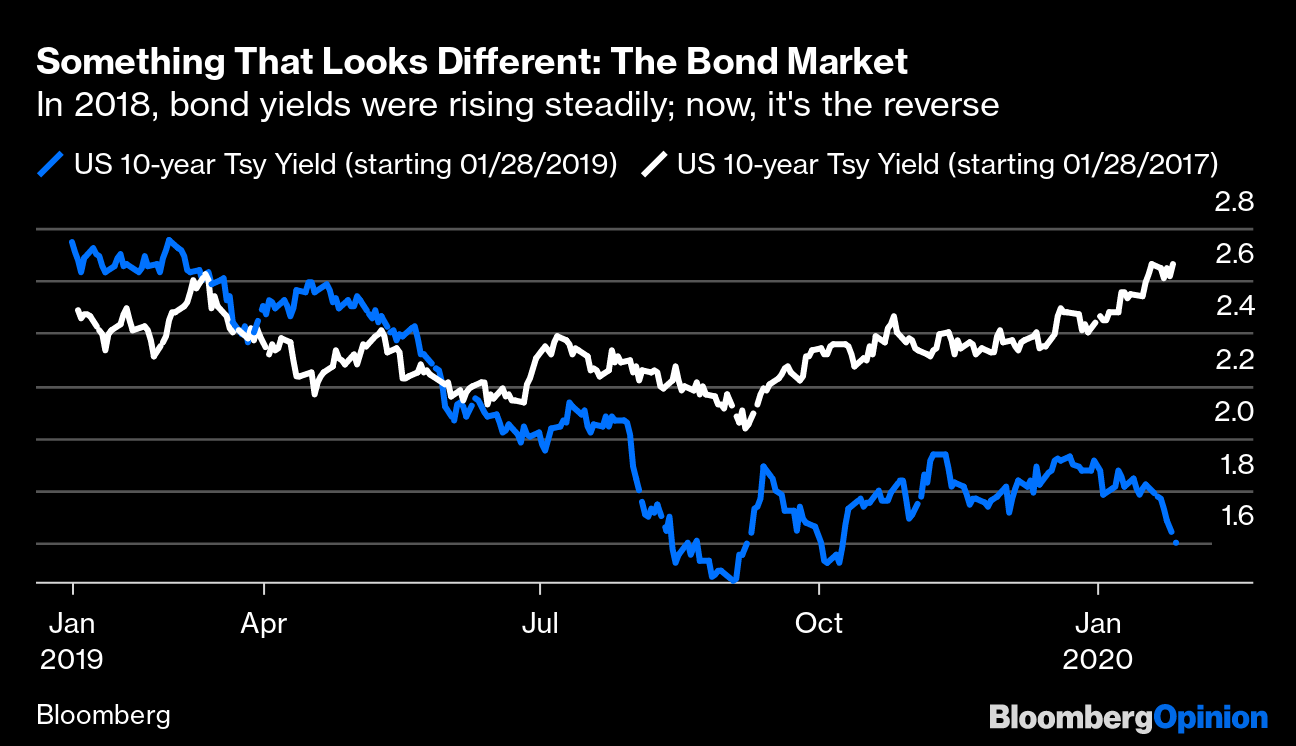

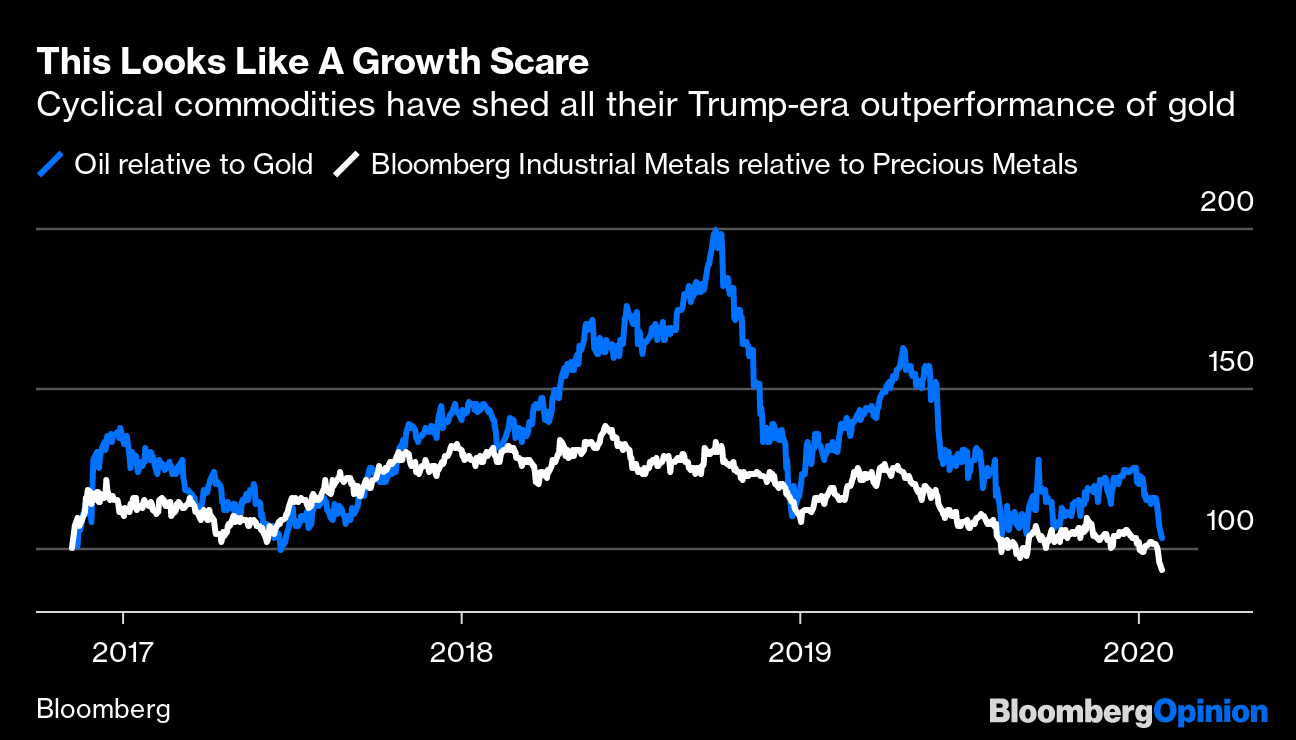

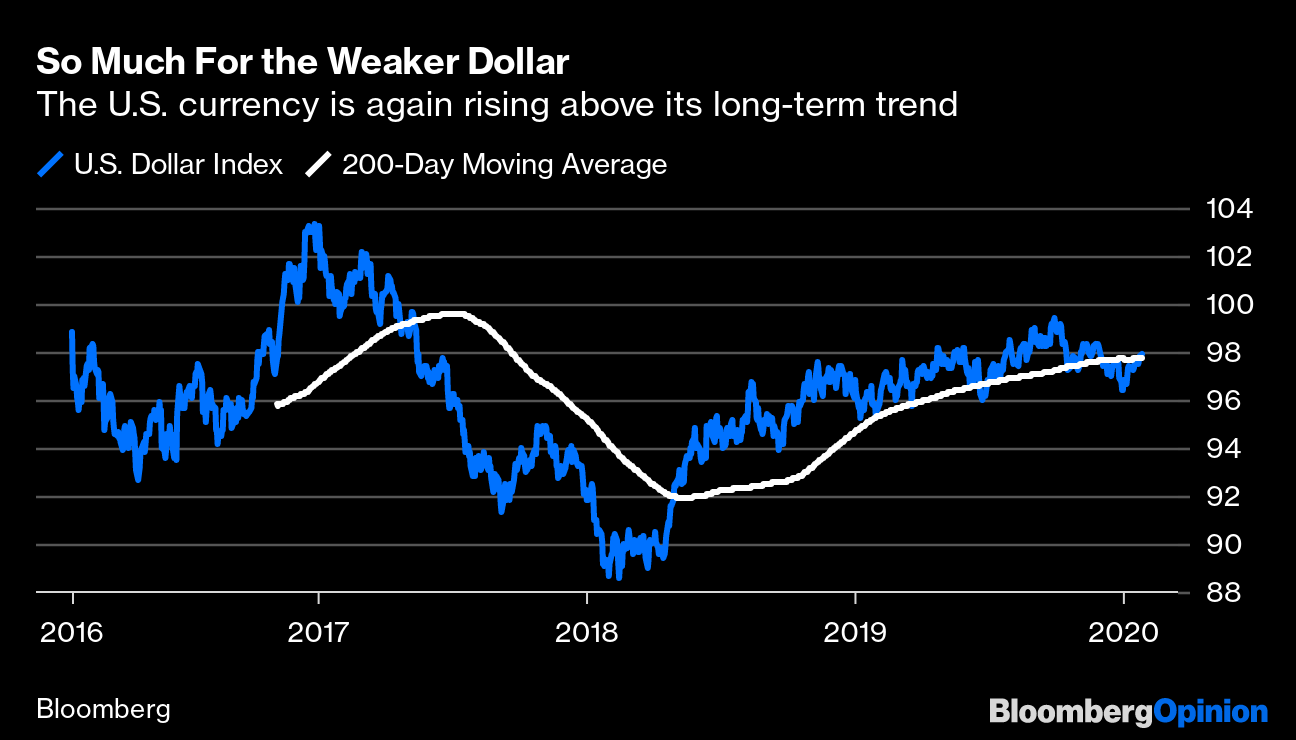

| World stock markets have just had their worst day since August last year, when the U.S.-Chinese trade conflict was deepening, and an inverted U.S. yield curve convinced many that a recession was on the doorstep. There is no mystery about the prime cause this time; the emergence of a novel coronavirus adds a frightening new risk, which cannot be glibly dismissed. It is beyond doubt that it will have a negative impact on this quarter's economic growth in China, as holidays are extended and travel is curtailed. The path of similar disease outbreaks in recent decades has followed a recognizable market template: There is a sell-off that lasts until concern reaches a crescendo, and the outbreak comes under control. Then it is time for a recovery. Sell-offs driven by previous epidemics have created buying opportunities. That is plainly the base case that many are still using, and Monday's 1.62% drop in the MSCI All-World index doesn't look excessive. But even if coronavirus was undeniably the catalyst for the declines of the last few days, are other things also afoot? If we look at the following chart, we can see that this reversal is remarkably similar to one that began on the same date two years ago. On both occasions, the S&P 500 Index had surged 25% in 12 months. And on that previous occasion, a very nasty correction, followed by a very nice buying opportunity, lay ahead: (And yes, I agree that overlay charts like this can fairly be called a kind of chart crime, but this is a comparison that seems to be on everyone's minds. We had what looked like a melt-up for equities two years ago, and the similarities to today's markets were as obvious two weeks ago as they are now.) This leads, however, to a very important difference. The correction of early 2018 was prompted by a rise in bond yields. Following the U.S. tax cuts, there was at last a belief that the global economy was going to break out of its deflationary slump and enjoy a coordinated recovery. Bond yields rose as a consequence — and that was enough to give the equity market second thoughts. The bond market over the last year could scarcely have been more different. Yields have been falling, reflecting concerns about global growth, and also the dramatic change of direction by central banks, which was itself largely driven by fears for growth. The 10-year Treasury yield is now almost a full percentage point lower than it was two years ago, and its trend is clearly downward. Indeed, if we take inflation expectations into account, the real 10-year Treasury yield has just gone negative, for the first time since last summer's recession scare. For bonds, this is a very different world from that of early 2018:  So a melt-up in equities two years ago foundered on fears of overheating, which made sense. This time a melt-up may end in a scare about lack of growth, which on the face of it makes no sense at all. As I commented last week, the symptoms of both a classic mania in the big internet names, and a bear market co-exist in the U.S. stock market. If we look at what Jean Ergas of Tigress Research calls the "full contact" safe havens, where investors dive for cover when they are truly worried, the picture of a true scare about growth appears to be confirmed. According to the Bloomberg commodity indexes, industrial metals have now under-performed precious metals over the period since Donald Trump was elected U.S. president; and the price of oil is collapsing anew relative to gold. These moves only make sense if people are worried about growth.  If we do have a growth scare then we would expect investors to run for the safety of the dollar. And that is exactly what they have done. The trade-weighted average of the dollar against its main trading partners is now above its 200-day moving average. The weakening trend that many hoped had already started will need to be delayed again:  It is true that coronavirus could yet be so bad as to change global growth on its own. We should all hope that this is avoided. But as these charts show, growth concerns have been building for a while. The last few days have accentuated a trend, rather than showing some big shift in response to a shocking new event. So it is fair to say that the coronavirus is a catalyst for growth fears, or even being used as an excuse to retreat from bets on growth.

However there is at least one specific currency issue that is plainly affected by coronavirus. The offshore Chinese yuan is still trading during the Lunar New Year celebrations. Ever since Christmas, it has traded below the level of 7 to the dollar, as part of the attempt to build a U.S.-Chinese trade peace. The measures to contain the virus plainly put pressure on the currency once more — and it has very nearly gone through the 7 level again. That helped drive a serious weakening for emerging currencies as a whole.

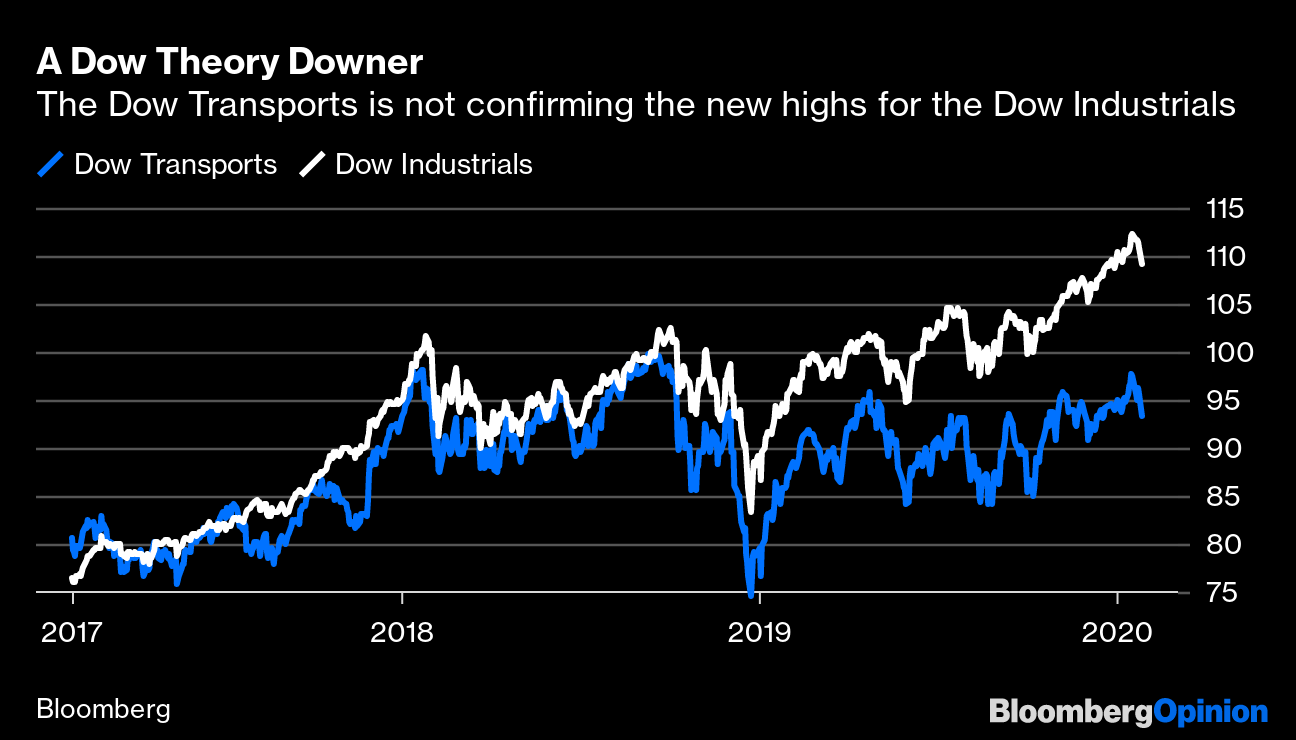

The U.S. badly wants a stronger Chinese currency. Its negotiators will surely understand why a new Chinese depreciation may be necessary, and they are anxious to avoid any resumption of any trade hostilities — at least until the U.S. election is over. A weakening yuan will at least be a complicating factor in some very difficult negotiations. So to this extent, coronavirus is a new factor that should prompt us to be more pessimistic about the world economy. Beyond that, however, there is deep worry about global growth. An underwhelming set of figures on industrial optimism from German manufacturers Monday was nowhere near as scary as the news on coronavirus, but contributed in full to a bad day. We should be careful about assuming that coronavirus can be resolved as quickly as other recent epidemics. But we should also be careful about any diagnosis that all of the markets' concerns are down to coronavirus. I said don't panic. That remains good advice. But that's a long way from saying don't worry. One for the Purists Regular readers will know that I loathe and detest the Dow Jones Industrial Average and all its works. I find it embarrassing that so many in the financial media still quote an "index" which they should know to be technically flawed and obsolete. That said, there is intuitive sense to Dow Theory, which holds that we can expect a strong rally if a new high in the transports or industrials average is confirmed by a new high in the other. And so if we follow Dow Theory, the events of the last few days are discouraging. The transportation index has conspicuously failed to regain its high from 2018 (in the chart, the two gauges are indexed to that high). Or to put it another way, this looks like another clear case where worries about the economy show that we shouldn't trust a rally in the stock market.

Books: The Magic of Minsky Moments….

To wrap up the long book club conversation on the ideas of Hyman Minsky, here at last is the transcript of last week's live chat, featuring Robert Barbera of Johns Hopkins University, who wrote the book "The Cost of Capitalism" about Minsky's ideas. For my money, the single most telling comment in the conversation is this line from Barbera: When you insist that people are rational about accelerating inflation risks, you make modeling in a highfalutin fashion easier. When you admit that people buy fewer cars when their price goes up but more stocks when stock prices rise, you blow the model up. It gets ad hoc and weird. This is very true. Asset price inflation is at least as important for the economy as the general level of goods prices, but follows different dynamics, and it is very difficult to come up with a model that incorporates both at the same time. The solution is either to keep an eye on two models at once, or come up with a very complicated model for a very complicated economy, and nobody feels like doing either of those things. Meanwhile, for those of you who thirst after yet more knowledge of Minsky, a Barbera paper on the subject, which is much recommended, can be found here, while this paper suggests that China's slowdown is already worse than meets the eye — even before we worry about the possibility of a pandemic or a Minsky moment. Justin Fox dug up this fascinating paper published in Manchester, England in 1867 outlining something very like the Minsky cycle — so we shouldn't blame all of what happened in 2008 on unduly complex credit derivatives. And it is very much worth reading this paper by the Nobel laureate (and husband of Janet Yellen) George Akerlof, trying to explain why Minsky-esque concerns about financial stability haven't been reflected in mainstream macroeconomics over the last decade. As always, feedback is very welcome. ...and The Anatomy of the Bear We now move on to "Anatomy of the Bear," a masterly attempt by Russell Napier to work out what linked the great bear market bottoms of the 20th century, and whether there was any way to spot them in real time. Could we have spotted the bottom of March 2009 when it happened, and is there an even deeper trough to come? Please start reading the book, and we will aim to hold an online chat about it in about a month's time. As ever, please send questions and comments to authersnotes@bloomberg.net. To prepare for this, you might want to watch a video I made with Napier, in his home ground of Edinburgh in Scotland, back in 2011. (You need to go to my old home ground of ft.com, but videos there are free to non-subscribers so it shouldn't be difficult to watch). It was one of the scariest interviews you will ever hear, and enjoyed quite an afterlife elsewhere online, largely because Napier was prepared to predict that the S&P 500 was heading on its way toward 400. (It is currently just above 3,200.) At the point of this video, he was predicting that the emerging markets, led by China, would soon have to start to tighten rates. It is worth watching the video carefully to work out where his ideas have gone wrong, and whether they may yet come true. His argument was that March 2009 was not a secular bear market low to match the great bear market bottoms he covered in his book; long-term valuations didn't hit the extreme lows they had seen in 1932 or 1982; and while there was fear, we never saw what he had always seen at the bottom of previous bear markets, which was apathy. Normally at the great buying opportunities, people are no longer terrified; they have simply lost all interest. The 2009 turnaround was far quicker and more abrupt than earlier bear-market bottoms. The critical difference with other bear markets was Ben Bernanke's Federal Reserve. Napier had predicted a strong rebound starting in 2009, which would perish once bond yields started to rise. The advent of quantitative easing in late 2010, a few months before the interview, put paid to that. Bernanke was determined not to make the same mistakes that the Fed had made during the Great Depression. And in this he was successful. But did he make other serious mistakes instead? And did he merely postpone a reckoning?

These are the topics we will be discussing over the next month. Please read the book, which is fascinating reading. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment