| We have climbed back to the top of the golden cliff. Now, what happens next? Two related landmarks were easy to miss amid Monday's continuing excitement about the tension between Iran and the U.S., but they matter. The first was a comeback: In April 2013, gold staged a sudden and dramatic crash, dropping 13.5% in two trading days. That confirmed a bear market from which the precious metal has only just, it appears, emerged. On Monday, gold's spot price in dollars at last exceeded its price from April 11, 2013.  Before its sharp decline, gold had rallied on the belief that the low interest rates put in place to combat the financial crisis would usher in inflation. And so when it slumped in 2013, various conspiracy theories moved through the ether to try to account for its worst collapse in three decades. Within a month, though, the drop was beginning to look prophetic. Soon after, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke ushered in what came to be known as the "Taper Tantrum" by suggesting that he was ready to start removing support for the bond market — which also began to acknowledge that the crisis had squeezed risks of inflation out of the economy. By that autumn — almost five years after the crisis — there was a growing recognition that inflation wasn't going to arrive. That leads to Monday's second major landmark. Real yields on 10-year U.S. debt (the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury with the inflation breakeven, a measure of consumer-price expectations, stripped out) briefly dipped into negative territory for the first time since August of last year. This occurred in response to the news from Iran, which sent bond yields falling while nudging up inflation breakevens.

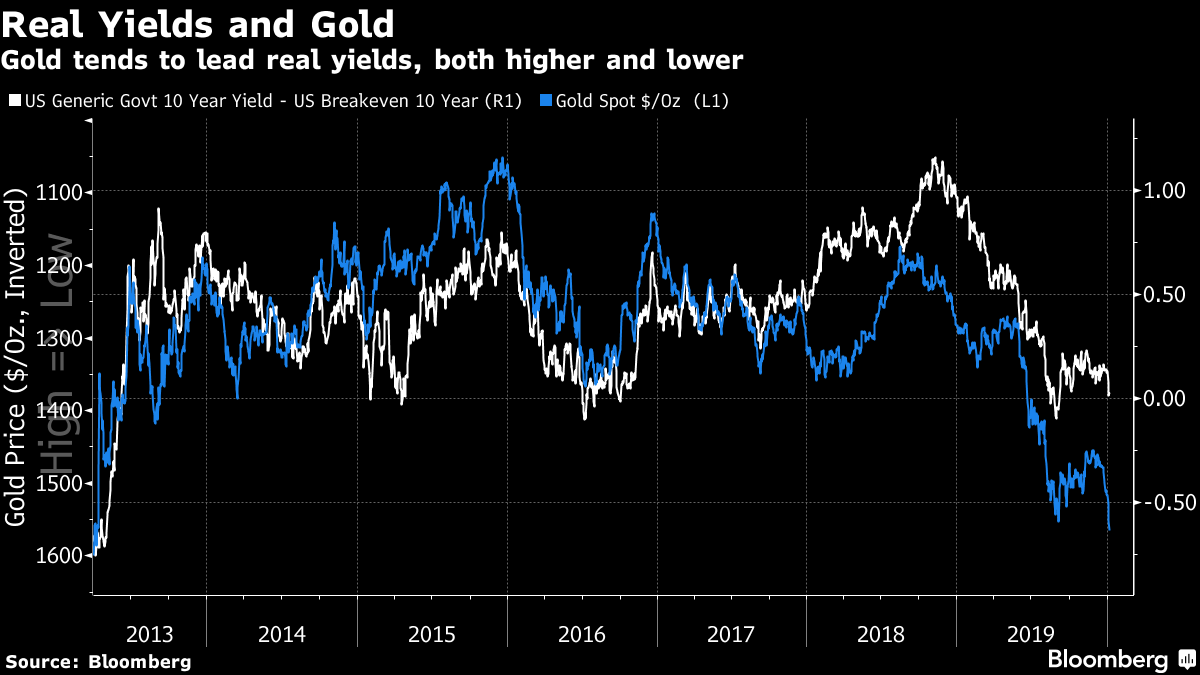

What to make of this? Looking back to 2013, we can see that real yields and the price of gold have tended to track each other, with gold generally moving a few weeks before real yields. If it has done so again, we can expect a further leg down in real yields, either through higher inflation expectations or lower rates:

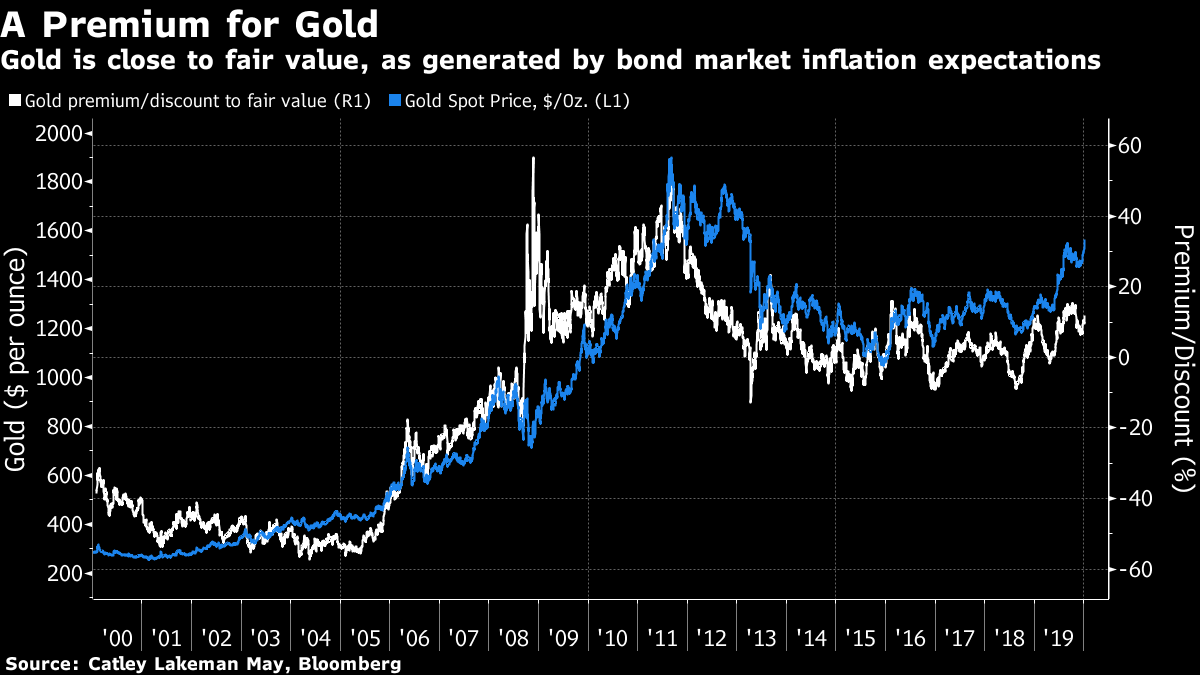

If gold's implicit prediction is right, it has two implications. The first and most important one is a belief that inflation is at last due to return, after many false alarms. The second is that gold is now settled in a bull market. So, is gold good value? The metal doesn't throw off any income streams, and has very few industrial uses, so it is very hard to come up with a measure of fair value. But the following chart, using data drawn up by Charlie Morris of Catley, Lakewood and May in London, is a heroic attempt to arrive at one. Morris devised a formula for fair value using the consumer price index and the average of 10- and 30-year inflation expectations. This indicator briefly showed that gold was wildly overpriced during the worst of the 2008 crisis, a phenomenon that may have been driven by the illiquid markets of the time, that created an unrealistic inflation forecast. Exclude this incident, and we see a steady bull market for gold from 2005 too 2011, followed by a steady bear market, where it moved to a discount. In the last two years, it looks as though it may have started another bull market. By Morris' calculations, gold is now about 11% over fair value.  Gold is still far from the confident prediction of runaway inflation that it briefly produced for a few years after the crisis, even though it is buoyed by safe haven demand at present, along with seasonal interest in gold jewelry, notably from China where the lunar new year is almost here, and by resumed interest from central banks. On the supply side, gold-mining groups are merging, creating a reasonable hope of avoiding over-supply in the near future. So, if this move in gold prices is confirmed by a move down in real yields, followed even by an increase in inflation, then this could be part of a bull market to match the one from 2005 to 2011. The critical question is whether the gold market proves to be right this time in its forecast of inflation. Books and the Cost of Capitalism And now for your regular reminder about the Bloomberg book club, which is this month tackling two books to introduce us to the ideas of the late Hyman Minsky, a once misunderstood figure who is now recognized as a giant of economic theory. Those prepared to tackle Minsky full-on in the original are reading his "John Maynard Keynes." Despite its title, this book isn't really about Keynes, and is more of a vehicle to introduce Minsky's own theory that capitalism is inherently unstable. Minsky writes very well, but there are some passages with graphs and Greek letters. As an accompaniment, or an alternative, there is "The Cost of Capitalism" by Robert Barbera, a friend of Minsky's and former Wall Street economist who is now at Johns Hopkins University. It is a brilliant and lucid explanation of Minsky's ideas, and he uses them to explain the disastrous credit implosion of 2008. With markets seeming almost unnaturally calm and taking even last week's shocking news from Iran in their stride, it is ever more relevant to ask whether stability is again creating future instability, as Minsky warned. It is very much worth using some precious spare time to try to wrestle with Minsky's ideas, and to try to come up with a better solution than his own proposal to nationalize all investment. It was largely because of the very left-wing solutions Minsky offered that his ideas tended at first to be ignored, but the challenge is to find a way of operating capitalism without falling victim to the process that Minsky identified. That process, as summarized by Barbera, is as follows: First, the persistence of benign real economy circumstance invites belief in its permanence. Second, growing confidence invites riskier finance. Minsky combined these two insights and asserted that boom and bust business cycles were inescapable in a free market economy — even if the central bankers were able to tame big swings for inflation. Bear in mind that Minsky passed away in 2006, and didn't have the benefit of the events of 2000, or 2008, to help him produce this hypothesis. It demands our attention, and it demands a serious attempt to find a better solution than Minsky's own. That is what we will try to do by reading these books over the next month. We aim to have an online conversation on the terminal near the end of this month, with Robert Barbera in attendance. If you have the time, please try reading one or both books, and sending any comments and questions to the book club's email address: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment