Coronamarkets The novel coronavirus from Wuhan continues to dominate markets. Stocks rallied Tuesday, after sharp falls Friday and Monday, but this doesn't mean there were any substantive signs of encouragement. Tuesday's news was again roundly discouraging.

Vincent Catalano, now chief markets strategist at Stuyvesant Capital Management Corp. in New York, asked sarcastically: "What happened? I must have missed it. Did they find a cure? Or was the disease financialmediaitis: For every effect there must be a cause?"

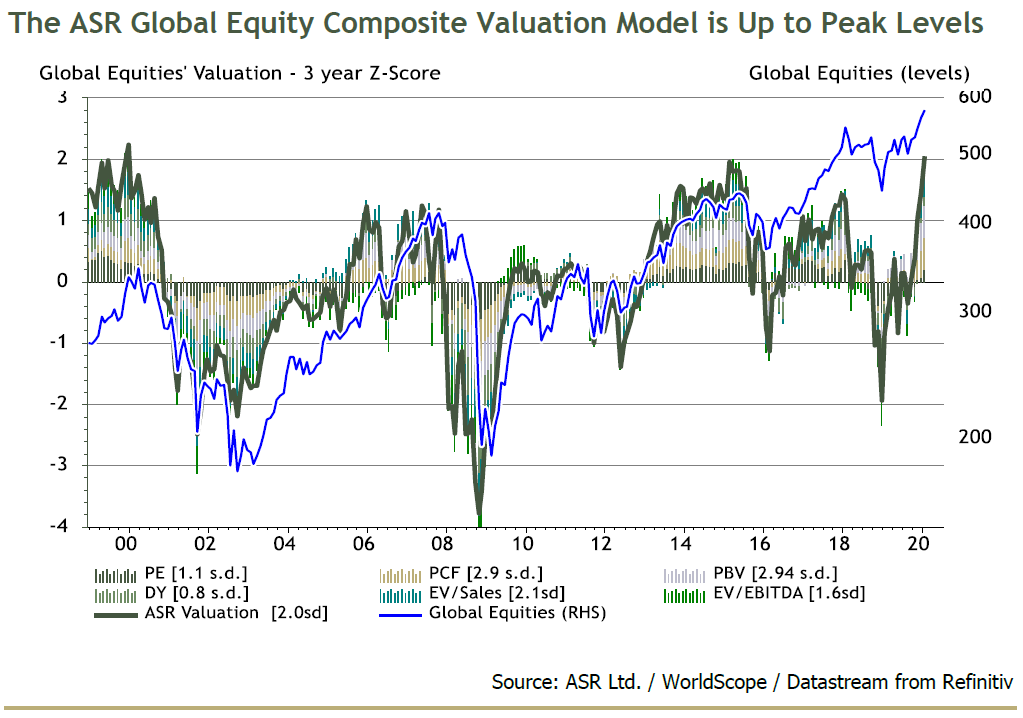

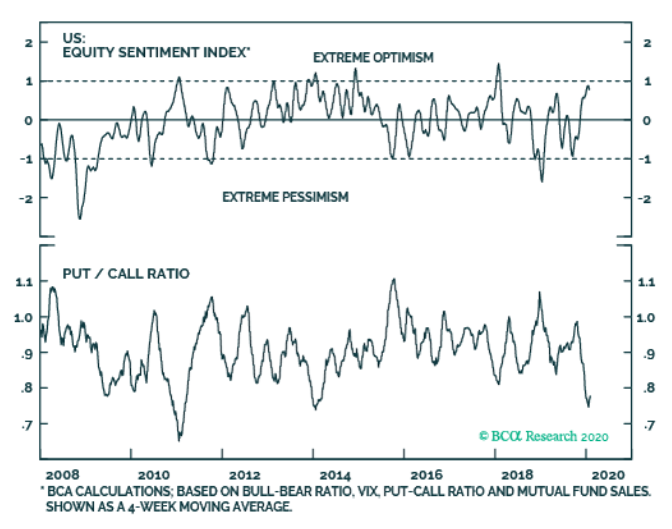

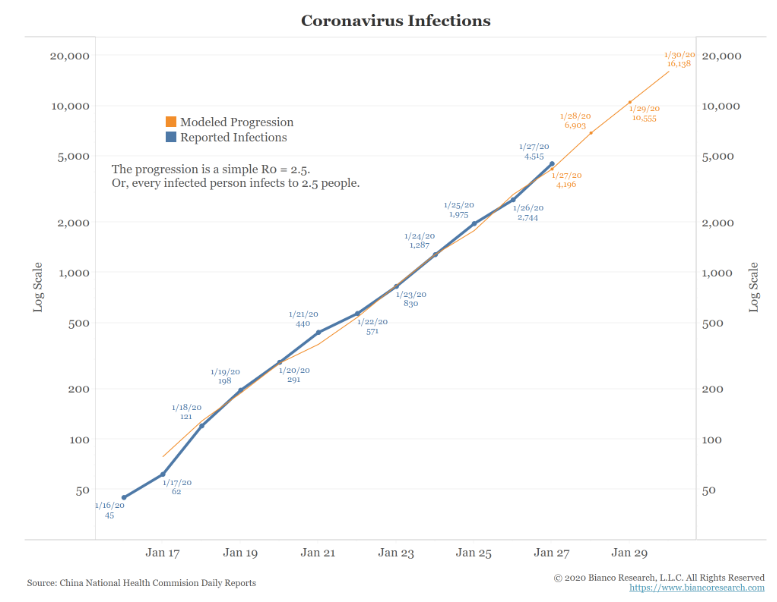

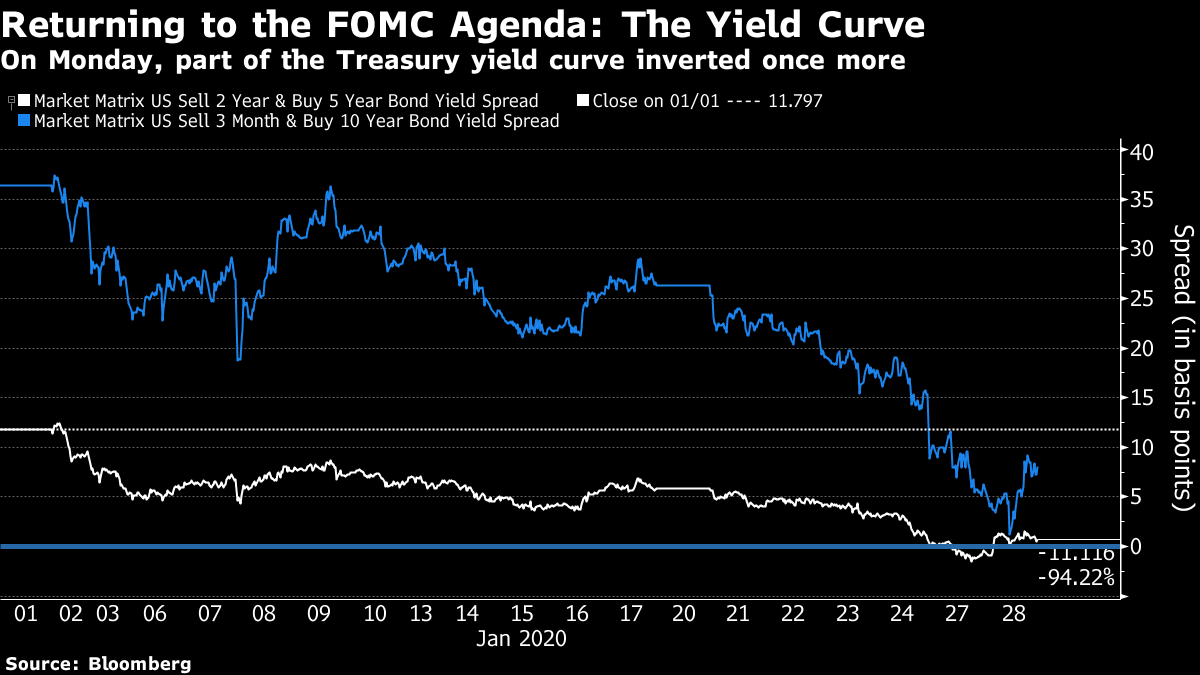

I think Catalano's point is well made. The financial media is often guilty of trying too hard to attribute every market move to some specific item of news. But he did agree with me that perhaps it is best to say that the coronavirus provided an excuse to sell stocks, rather than a reason. And with valuations looking excessive, particularly in the U.S., selling some stock is appealing. It is never a bad idea to sell something for more than it is worth. How excessive are valuations? This chart, which smooshes together several different measures of global stock valuation, expresses it as well as anything. It comes from Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. in London:  All the measures that went into this chart are expressed in terms of their standard deviation from the norm. Earnings at present look as though they are on unsustainable tear, supported by strong profit margins, so price-earnings multiples don't seem excessive. But multiples of cash flow, sales and book value all look extreme. Put them together and, on this basis at any rate, stocks haven't been this overvalued since the top of the dot-com boom 20 years ago. An excuse to take some profits was welcome. Meanwhile, BCA Research of Toronto has its own composite measure of short-term sentiment. On this basis, U.S. stocks looked almost as overbought as they had been at any stage in the post-crisis decade. The put-call ratio, showing the balance between those positioning for future gains and losses through the options market, in particular shows pessimism at its lowest since 2011. So, again, an excuse to sell was welcome.  So we shouldn't be too excited about the market reaction on Monday. As Richard Bernstein of Richard Bernstein Advisors puts it, "Bad news is often shrugged off earlier in a market cycle, but can more easily accentuate volatility in late cycles when valuations are stretched and leadership narrows." This is, incidentally, reason to expect higher volatility this time around than during the 2003 SARS outbreak, which came at a market bottom, when many were preoccupied by the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The fact that volatility is only to be expected doesn't give any great cause for comfort about the epidemic. The coronavirus is so scary precisely because the risk is so difficult to measure. It might conceivably transform the global economy. That is very unlikely, but it is impossible to measure exactly how unlikely. So while there is little to be gained from panicking (other than crystallizing some nice gains in the U.S. equity market, perhaps), it is still wise to keep a close eye on the progress of the epidemic. So what guidelines are there for the future of the coronavirus? Jim Bianco, president and founder of Bianco Research LLC in Chicago (and a Bloomberg Opinion contributor), shows that the spread of this epidemic, like any other, has been geometric. Thus, if we put new cases on a log scale, they look like an almost perfectly straight line:  The bad news is that we can expect this geometric progression to continue for a while. That implies much human pain, but as the efforts to contain the spread have only just started, it is inevitable. The good news, from the point of view of investors, is that this gives those of us without medical expertise some handle on how to judge the spread of the virus. If this menacing line of reported infections begins to have a shallower slope, that should be good evidence that the outbreak is beginning to come under control. That in turn should mean (cold-blooded cynical investor alert) that there should be a buying opportunity. Similar epidemics showed that this point when the spread began to be contained came after about three weeks. That should offer a good rule of thumb for investors. If the line on this graph is still a perfectly straight upward slant by the last week of February, therefore, it should be time to get very worried indeed, and to start looking at the possibility that this epidemic does serious economic damage. If the disease really does keep spreading like that for another month, we can expect that the outcry in the population as a whole will be deafening by then. Finance won't be the greatest of our concerns. But just to repeat the usual caveats; I am not a doctor, and I don't even play one on TV (or any other Bloomberg outlet). And there is no reason at present to assume that the situation in a month's time will be so dark. For now, as an investment commentator, I would continue to say that there is little reason to do anything about coronavirus, barring a nudge down in expectations for Chinese growth in this quarter, and a nudge down in the likely level of the Chinese currency. There is no need to react to any other bad news until it actually happens. FOMC I checked my calendar and suddenly realized that we will be hearing from the Federal Open Market Committee on Wednesday. This will be one of the least-heralded monetary policy meetings of recent years, which is always good news for central bankers. Nobody much expects any moves in interest rates, while the expansion of the Fed's balance sheet since the overnight repo market grew angry four months ago has persuaded many that the stock market is safe again. This month's FOMC is unlikely to make much news. That doesn't mean, however, that it can safely be ignored. And it certainly doesn't mean that the Fed's governors have nothing to worry about. As Brian Chappatta points out in Bloomberg Opinion, the Fed still has a lot of explaining to do about its balance sheet operations, now almost universally known as "Not QE." It might help the Fed's credibility if it stopped denying that these moves are quantitative easing and accepted that they are having the same effect as QE, whatever the intention. The Fed also has to contend with the fact that one of the key problems prompting its U-turn last year, the flattening and then inversion of the Treasury yield curve, isn't over. Market moves Monday were plainly affected by coronavirus-driven anxiety; the spread of five-year over two-year bonds briefly inverted, while the spread of 10-year over three-month bond yields, regarded as a great recession indicator, came very close.  The coronavirus is scary, of course. We can all agree on that. But the fact that headlines about a flu outbreak in China were enough to drive quite such an outcome in the bond market, at a time when stocks are behaving as though the global economy is roaring ahead, should give us all cause for concern. It certainly makes life harder for Jerome Powell and his colleagues at the FOMC. Books, Etc. This is your latest reminder that the Authers' Notes Book Club has now moved on reading "Anatomy of the Bear," a history of the 20th century's bear markets and how to spot that they had ended, by the financial historian Russell Napier. It's a very interesting read that became a cult classic among investors at the time of the global financial crisis.  If anyone is interested in Napier's current views, he has done some podcasts recently. Here he is on MacroVoices, in an interview recorded a week ago. He also talked with former colleague Merryn Somerset-Webb (who wrote the foreword to the latest edition of "Anatomy of the Bear") on The Money Podcast in March of last year. His focus for now is on the risks of a credit crisis, particularly in China and the other emerging markets. (That might take us back tothis month's conversation about Minsky Moments and whether they can happen in China). We are aiming to chat about the book online with Napier in the first week of March. So you get to spend the gray and gloomy month of February reading about bear markets — or alternatively, you get to remind yourself of how easy investing is when everything is cheap. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment