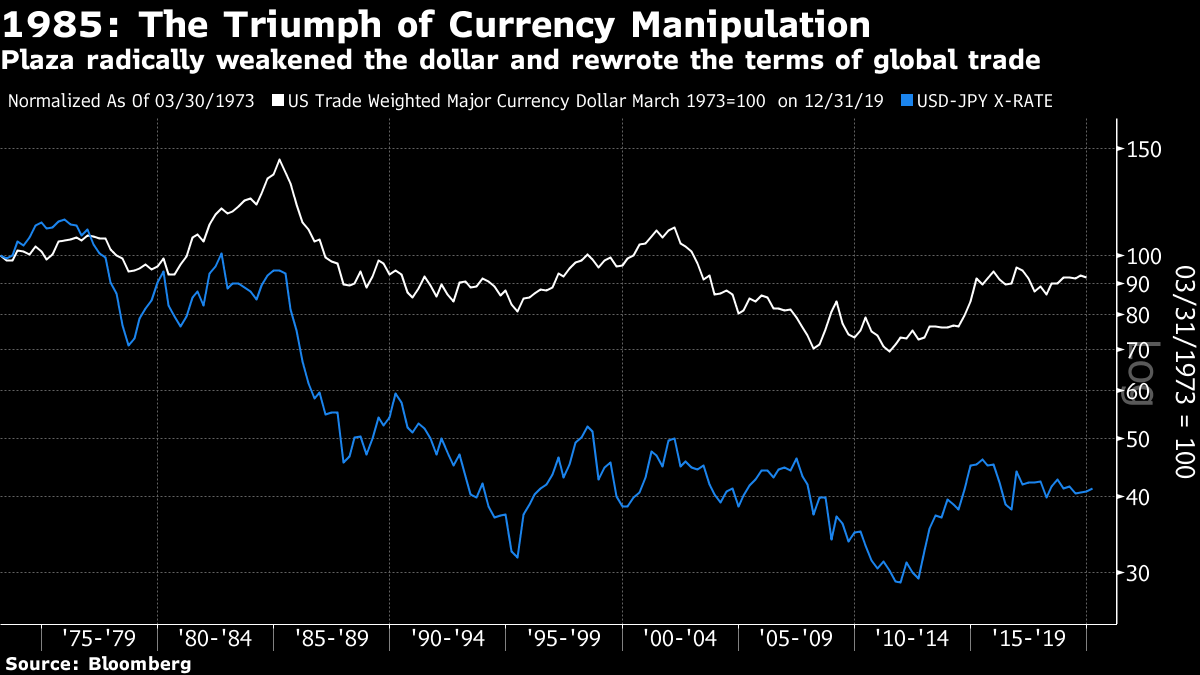

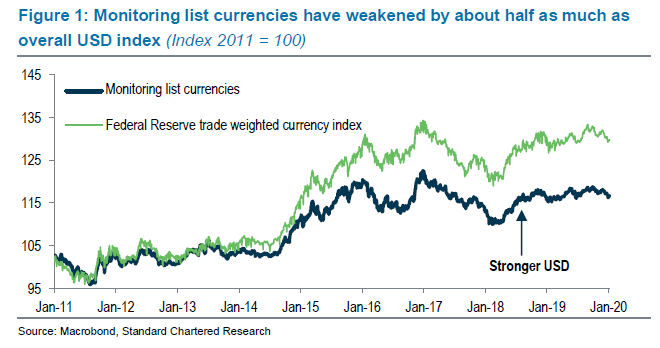

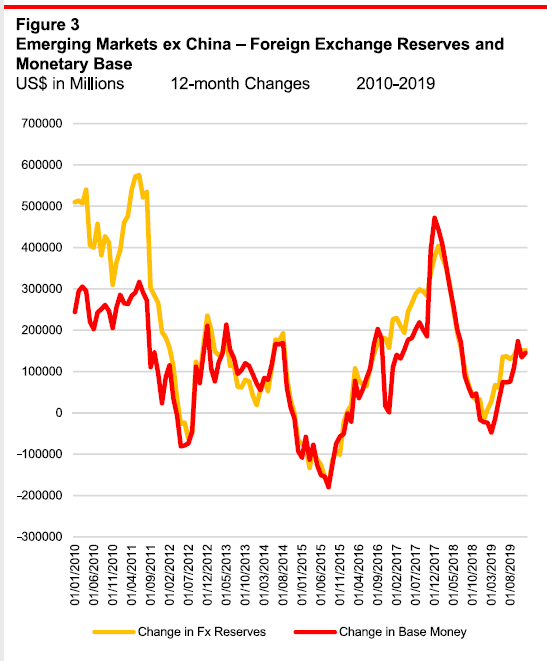

Plaza Discord New York's Plaza Hotel, sitting at the southeast corner of Central Park, is a hallowed landmark. A setting for "The Great Gatsby," it became a milestone in the career of Donald Trump as he first bought it in 1988, and subsequently was forced to sell it in 1995 amid bankruptcy proceedings. In the foreign exchange world, the Plaza is inextricably linked with arguably the most ambitious currency agreement ever made, and it is the standard against which the moves toward a U.S.-China trade deal will be judged. In 1985, the Plaza hosted the agreement between global central bankers and finance ministers to intervene to weaken the dollar and strengthen the Japanese yen. This was at a time when the dollar was at its strongest since the end of the Bretton Woods era 14 years earlier (then, as now, after an eight-year upward trend), while the stunning export-led growth of Japan was prompting the same kind of complaints that surround the growth of China today. Over the next few years, the dollar steadily weakened, the yen strengthened, and central banks oversaw a far more lenient monetary policy. The dollar has never again been so strong, while Japan has never since enjoyed such competitive terms of trade when it tries to sell to the U.S.  There was more to the geopolitical machinations of the mid-1980s than currency. Everyone wanted the chance to ease monetary policy together, as global inflation began to abate. As Michael Howell, head of Crossborder Capital Ltd. in London points out, there were other close parallels to the situation today, with Japan taking the place now occupied by China. With Japan forced into monetary accommodation (which helped to create the conditions for its asset bubble at the end of the decade) and the Federal Reserve also easing, other central banks had no choice but to follow suit, arguably helping to create the overblown conditions that led to the Black Monday crash in October 1987. The currency agreement, negotiated in secret, was in many ways intended to avert an ever angrier Congress from resorting to direct trade protectionism against Japan. Meanwhile, the very day after the Plaza Accord was announced, President Ronald Reagan inveighed against "counterfeiting and copying" of American products, as the agenda moved on to thwarting alleged Japanese attempts to achieve technological dominance. But the critical link in the chain came with Japan's agreement to strengthen its currency. If the Plaza Accord is the gold standard for deals between the U.S. and a rising Asian economy that threatens its dominance, where does the agreement taking shape between the U.S. and China rank? Obviously it is far less ambitious, and both sides seem far more prepared to resort to more aggressive measures. But there are similarities. Ahead of Wednesday's scheduled signing of the "phase one" agreement came the U.S. Treasury's announcement that it no longer deemed China a currency manipulator. This was a strange undertaking. The decision to label China last August was blatantly political and came many years after Beijing had abandoned its policy of keeping the yuan artificially weak. Strangely also, as this chart from Standard Chartered Plc shows, countries being officially monitored for manipulation have on average seen their currencies perform much more strongly against the dollar than most others:  The currency manipulation announcement should at least be taken as a signal in the negotiations. It followed a sharp strengthening of the yuan that took the currency back to its level at the beginning of August — when President Trump's surprise announcement of new tariffs had prompted a sharp devaluation below the level of 7 per dollar.  To use another popular phrase of the moment, this looks like a quid pro quo. Further, as Steven Englander, foreign exchange strategist at Standard Chartered, points out, the Treasury's official announcement implicitly assumes that China has almost total control over its currency. "The Chinese authorities have acknowledged that they have ample control over the exchange rate," the Treasury says, adding: "China needs to take the necessary steps to avoid a persistently weak currency... Improved economic fundamentals and structural policy settings would underpin a stronger RMB over time." Englander notes that the Treasury never suggests market forces or tariffs could have driven China's depreciation. Instead, it reads almost as though China can set the value of its currency at will — something that took massive and concerted intervention after the Plaza Accord. He adds: The text can be read as suggesting the following syllogism: (1) the CNY is weak; (2) China has many tools to affect the currency; (3) China is responsible for any currency weakness. For investors, the question is whether this is a Treasury aspiration or whether China has indicated as part of the phase one deal that it will strengthen the CNY as tariffs are removed. In other words, the U.S. is behaving almost as though this is part of an agreement as broad-reaching as Plaza. That in turn implies that China can now proceed with aggressive monetary easing, and that in turn implies very good things indeed (at least in the short term) for Chinese assets and for emerging markets more broadly. As if to back this, China last week announced a reduction in banks' required reserve ratio, effectively allowing more lending in the economy. After a year in which the People's Bank of China seemed preoccupied with the macro-prudential issues of averting a credit crisis in over-leveraged local governments, it appears that China may be opening the spigots again. The U.S. has already done so. And as Crossborder Capital shows, reserves and liquidity are already beginning to grow in emerging markets outside China:  Put this together, and the fresh risk appetite in world markets grows easy to understand. There was money to be made in the late 1980s, even if a few asset bubbles formed as a result. It is also evident that both China and the U.S. regard currency as a central element in their trade dispute. But now note the differences with Plaza. That earlier currency accord preempted tariffs. This time around, the tariffs are already in place, and the shift in the currency is only part of a package to avoid extending them further. The issue of intellectual property remains unresolved. And China, unlike the Japan of 1985, is armed with nuclear weapons. Further, this "America First" U.S. administration is unlikely to be able to coordinate with other finance ministries and central banks the way its predecessors did. Now add the critical issue that China's economy isn't in anything like the rude health of Japan's in 1985. It is attempting a difficult transition, and while the PBOC may be happy to stimulate the consumer, it has to avoid channeling credit to corporations or housing, which appear over-leveraged. The fact that the tariffs aren't being extended may help its economy in some psychological way, but as most remain in place, it isn't clear that this will have much practical impact. We have a blueprint for what a U.S.-China deal might look like, but that was a long time ago, and closer examination of where the two sides have reached suggests it is still a long way away. If the Chinese economy can show some strength to quell the doubters, then the current optimism should be justified. As it is, the developments of this week should be taken as useful, incremental and symbolic moves, but not much more. One for the Books Finally, a reminder about the Bloomberg book club. This month's selection offered a choice between Hyman Minsky's "John Maynard Keynes," in which he introduced his theory of the inherent instability of capitalism, or Robert Barbera's "The Cost of Capitalism," which offers a modern restatement of Minsky's theory and applies it to the global financial crisis. Barbera will be discussing both books in a live chat on the terminal, on Thursday next week (Jan. 23), from 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., New York time. You can follow the conversation by going to TLIV on the terminal. To make comments or ask questions, send an email to the book club's address: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment