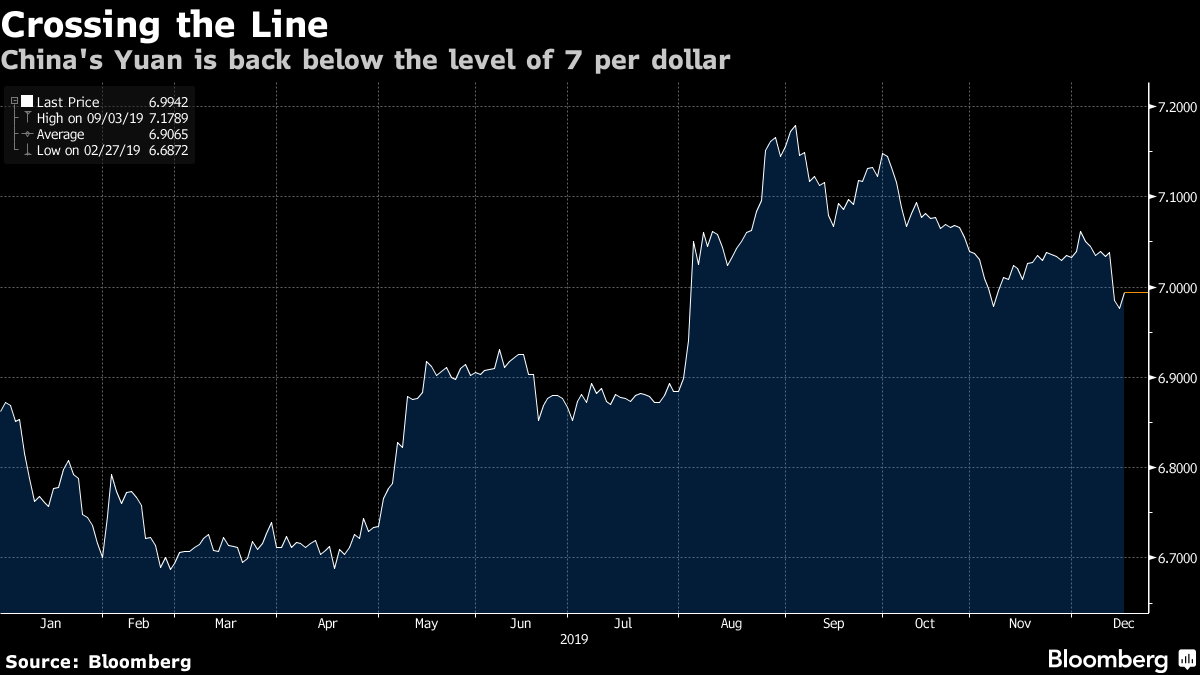

A Deal's a Deal. In markets, as in life, it is necessary to start from where you are. We now have a "phase one" trade deal between the U.S. and China, to go with a divorce agreement that will allow the U.K. and the EU to part ways. Both deals are incomplete, and both follow conflict that has been damaging. In the case of Brexit, it is hard to see how anyone will be any better off as a result. But that isn't what matters, at least for markets in the short term. What matters is the likely shape of the future, and how it has changed compared to what we already knew. The trade negotiations between the U.K. and the EU will be fraught and unpleasant. It is rare for a trade negotiation to start with one side taking exceptionally favorable access to by far its largest trading partner and asking for something worse, which is what the U.K. has decided to do. So it is also difficult to predict the outcome. But a few months ago there was a significant possibility that the U.K. would leave without any negotiated settlement, which raised the risk of a sudden stop for the trading system. And the risk of another year of damaging political uncertainty has also been erased by the Conservatives' decisive victory under Boris Johnson. The plan now is to "get Brexit done," opponents have to put up with it, and investors know exactly where they stand. This should strengthen U.K. and EU asset prices — albeit not that much as the news was already widely discounted. But what of the U.S. trade deal with China? This is much harder to handicap. It isn't clear what the U.S. is ultimately aiming for, and there is a range of issues that go beyond trade. As many have commented, the relationship between the world's hegemonic economic power and a rising rival will take years to resolve on even the rosiest scenarios. And while the issues are real, there are plenty who believe it was a serious mistake for the U.S. to resort to tariffs in the first place. So how should we gauge success? This is one of the best measures:  China's currency is still carefully managed, and for years was deliberately manipulated to keep it too cheap. After the announcement of a new round of tariffs on Aug. 1, authorities allowed the yuan to weaken above the round number of 7 yuan per dollar. Now, it has edged back below 7. The actual round number is arbitrary, of course, but round numbers matter to foreign exchange traders and trade negotiators. It is a clear sign of peace from China, and exactly what the Americans wanted to see. Cordiality has returned. This is a tangible and visible measure of it. For another important gauge, try this:  President Donald Trump wants a weaker dollar, which makes American exports more competitive. By the eve of the tariff war, that is exactly what he had. Then the dollar rallied because of the trade tensions. When risk is high, investors seek the haven of the U.S. dollar and drive it higher. In the process they render U.S. exporters less competitive, and vitiate the purpose of the tariffs. As the chart shows, by the end of last week Bloomberg's dollar spot index had returned to almost exactly its level on election day, with a downward trend. Its real effective rate, taking into account higher U.S. inflation, is still above election day, but if perceived risk continues to abate, we can expect further weakening. That is good for virtually everyone. Currency markets matter, and they show that the Americans have won something tangible — a weaker dollar — while the Chinese have given something tangible, in a stronger yuan. So we should take the deal seriously. The main points that explain this outcome: - This is much better than might have been feared. The month, after all, started with Trump saying he was prepared to wait until after next November's election for a deal.

- It is also better than a reasonable base case as of a few weeks ago. Markets were anxious that the new tariffs scheduled to start on Sunday wouldn't happen. But beyond, there has also been a partial roll-back of tariffs already in place — the first time this has happened since the conflict broke out.

- The future looks better than it did two weeks ago. The possibility of a serious escalation has been avoided, and the presidential desire for a deal should trump everything (at least until he wins his second term).

- The future looks no better than it did two years ago. The risk of lasting damage to the world's two largest economies has receded. But nothing about the deal improves the terms of trade for anyone. Leading indicators of global trade and U.S. manufacturing were flashing optimism two years ago. Both are now below the level of 50, signaling contraction:

I continue to think that both Brexit and the trade war are bad ideas (although they attempt to address genuine problems). But even for those who think that interruptions of free trade will end up making us worse off, the chance of serious damage has undeniably reduced. To borrow my colleague David Fickling's phrase, the U.S. has agreed to stop hitting itself in the face. This justifies a strengthening in risk assets and a move away from havens. As both outcomes had been widely discounted in advance, we shouldn't expect too big a rally. Nevertheless, they are reason for cheer. Incentives Work... It is established investment lore that hubristic behavior by CEOs can tell you a lot. Avoid companies that have just spent a lot on flagship new headquarters. And steer clear of those where insiders are selling.

It is also established lore that incentives work. Give someone an incentive to do something, and they will do it.

Putting these beliefs together, new research suggests, might be a good way to spot some good stocks to own, and some to avoid. Looked at more rigorously, fast asset growth in a company can often be a red flag, as it suggests empire-building may be taking priority over shareholder value. Meanwhile, buying back shares is a sign that managers believe they are undervalued. How far can either signal be trusted? A lot, it turns out, provided we combine them with information on how exposed a company's executives are to its share price. An ambitious study for Financial Analysts Journal by Shu Yan of the Spears School of Business at Oklahoma State University and a group of colleagues tried constructing a portfolio in the following way: - For companies with low managerial incentives (meaning top management didn't gain much from incremental improvements in the share price), it sold short those with high asset growth, and bought those with low asset growth;

- For companies with high managerial incentives, it shorted those that were issuing shares (showing management considered them overvalued), and bought those that were shrinking the float (showing that management thought the stock was cheap).

To cut a lot of mathematics short, the strategy worked beautifully. It delivered returns comfortably above the market, even after taking into account transaction costs and established investment factors such as value and momentum. You can trust the market-timing decisions of heavily incentivized managers, and you can thoroughly distrust the empire-building of managers who aren't incentivized. As of Monday, the paper should be available here. Sometimes They Work Too Well One final question: does this mean that basing executive compensation on an extreme exposure to the share price is a good idea? Not necessarily. Stock incentives can be self-defeating. It costs shareholders money to bestow stock on managers and executives, who then become interested only in pumping up the short-term price. As the paper shows, heavily stock-incentivized executives aren't going to accumulate wasteful assets, which is good. But they are also less likely to invest in productive and profitable assets, if it involves risk and lower returns in the short term. In Productivity and the Bonus Culture, the veteran British investor and economist Andrew Smithers argues that the slow economic growth of the last decade is more due to demographics and low productivity than to the immediate effects of the financial crisis — and that linking executive pay to share-price performance has been a key element in diminishing productivity. Until now, the positive impact of carefully managed balance sheets and stock repurchases, along with historically low interest rates, have allowed share prices to rally regardless. But the ongoing damage to the economy, on Smithers' argument, could be severe. For a publicly available presentation of his thinking, published in 2013, click here. For the long term, we need to move away from incentivizing managers this way. In the short term, assume that if a company is expanding its assets even though managers have a heavy incentive to maximize the share price, then they really have a good reason to be buying. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment