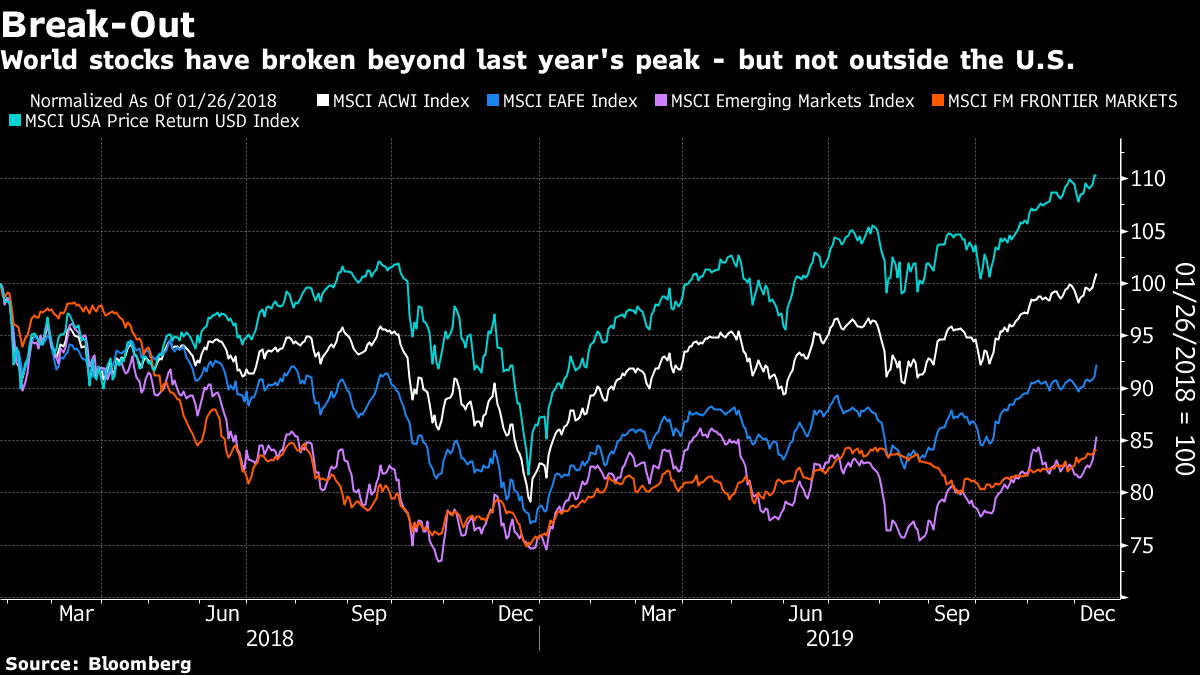

| The records are tumbling. Enough positive factors have come together for the MSCI ACWI (all-countries world index), which includes emerging and developed markets, to hit its first all-time high since the sudden eruption of volatility at the end of January last year. But that breakout (a phrase that recurred many times in the sell-side literature on Monday morning), still owes almost everything to the U.S. Emerging markets, frontier markets, and the rest of the developed world (represented by the EAFE, or Europe, Australasia and Far East index) have started to trend upward, but all remain below their January 2018 highs:  Is this a breakout we can rely on? We know that Brexit uncertainty has abated, and that the critical trade conflict between China and the U.S. has been contained for the time being. Neither of these things were true in the summer, when world stocks were sagging alarmingly. While the significance of both can be overstated, these are plainly reasons for stocks to be higher than they were before. What else has changed? The main "new" bull points seem to be: - Liquidity has picked up emphatically since the summer, thanks in large part to central banks. The seizure of the U.S. overnight market in September, which forced the Fed into resuming asset purchases begins to look like one of the most fortuitous accidents in market history.

- Manufacturing PMI surveys appear to have turned the corner, at least in Europe, which was the center of the greatest concern. And virtually everywhere, including the U,S., where the manufacturing PMI is still below the 50 level, new orders are exceeding inventories, in a sign that a restocking boom could be coming.

- Politics is a little less scary. Suddenly we know that a non-populist Conservative government will hold power in the U.K. for the next five years, even if it calls itself "The People's Government." And Senator Elizabeth Warren's summertime boom in the polls has proved short-lived. The chances of a more moderate Democrat taking on President Trump now look stronger.

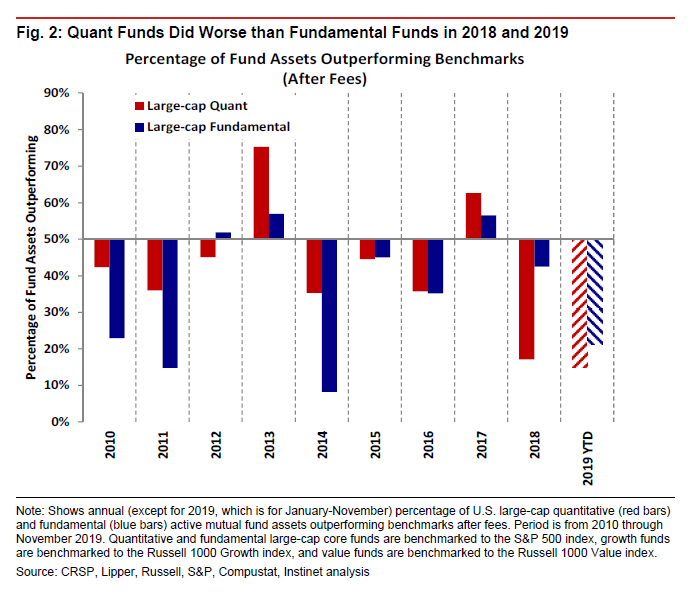

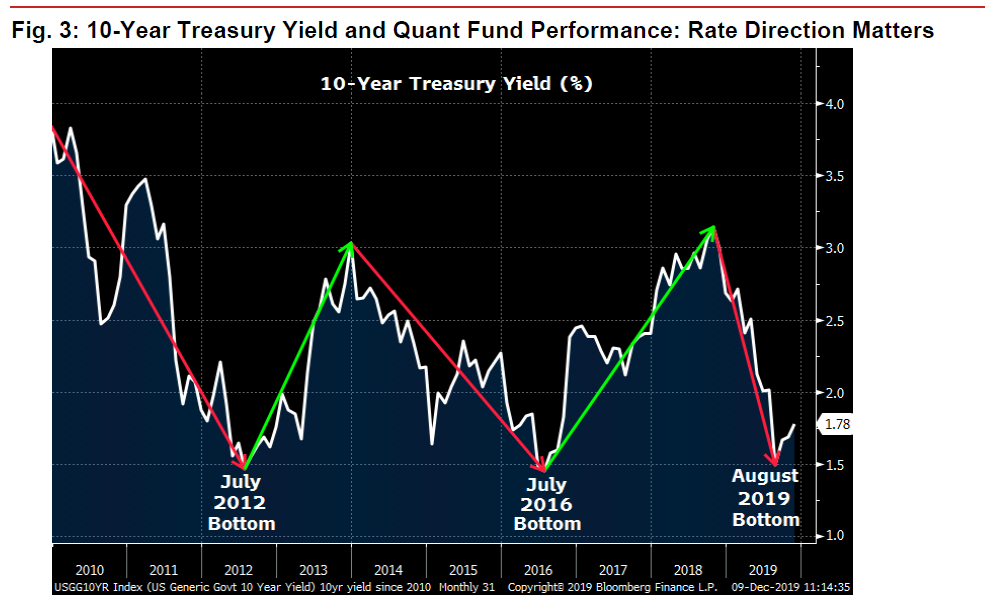

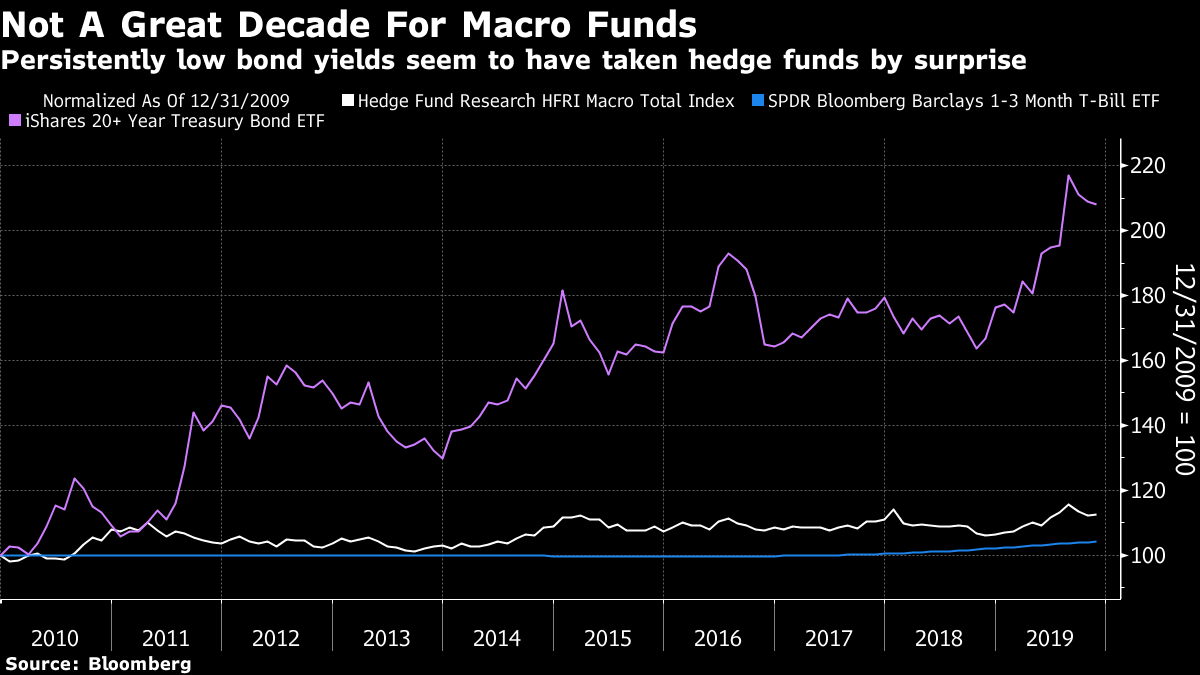

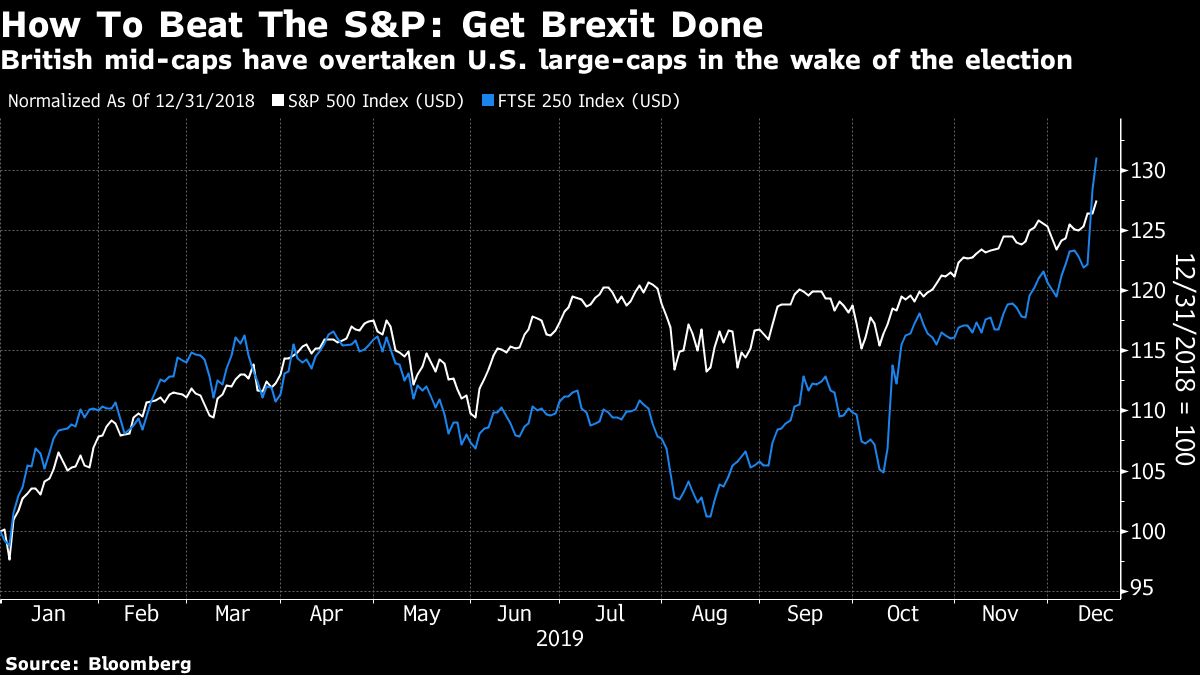

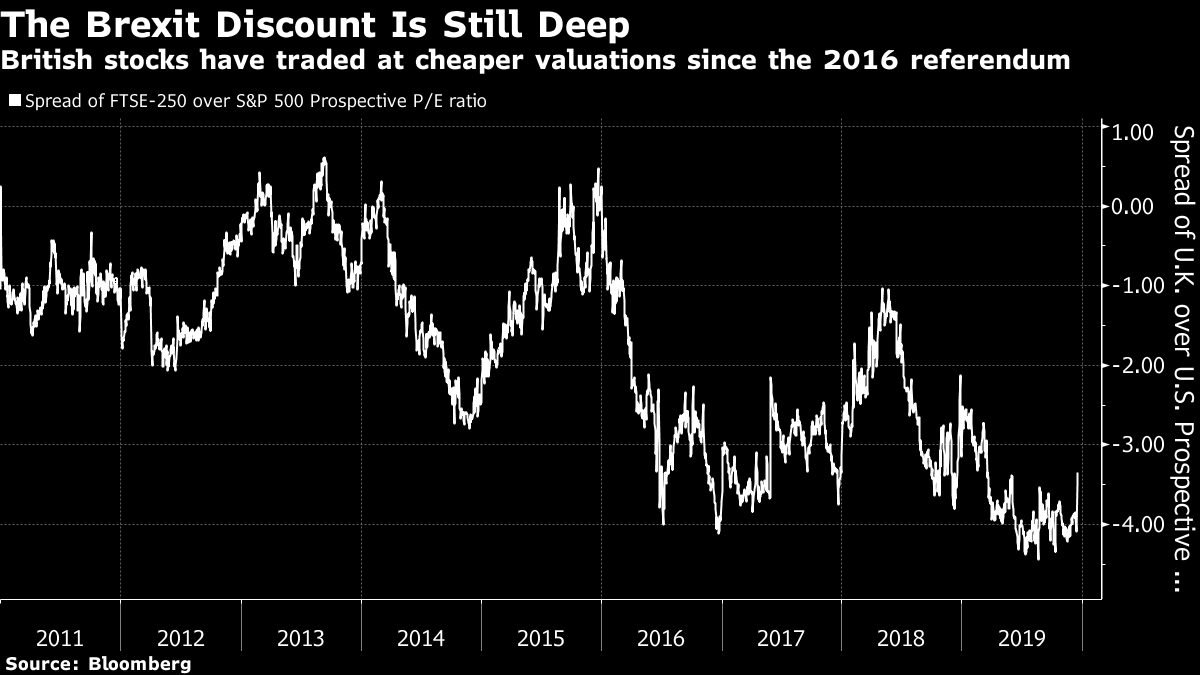

Beyond that, valuation continues to counsel against buying U.S. stocks, and in favor of buying stocks more or less everywhere else. Whether the "new news" is as good as it can be made to seem is open to question. Politics in particular could provide a lot of nasty shocks. But the mood has still palpably improved since the season of new year predictions started last month — and it is unlikely anything will upset the apple-cart between now and the end of the year. Charts showing a market breakout are cheerful. Others aren't. Previously, we have looked at charts showing the extreme difficulty of beating the S&P 500 in recent years. That is a real problem for traditional stock pickers managing a portfolio of a few dozen large companies; it is prohibitively difficult to run such a portfolio well enough to beat the market and still have money left over to pay a management fee. The answer was supposed to come from the quants. Greg Zuckerman's book on James Simons, the mathematics professor who founded Renaissance Technologies LLC and appeared to find the Rosetta Stone for beating markets, has justly received many plaudits in the last few months. Quants, avoiding human mental shortcuts and emotions, can beat the market. Just look at Simons. And, unlike Simons, they don't have to charge that much to do it. But this year has seen a continuation of a "Quant Winter" according to Joseph Mezrich, head of quantitative strategy at Instinet LLC. Earlier in the decade the quants had shown an ability to beat fundamental long-only equity managers, even if many of them failed to beat the market. For the last two years, however, most have lagged behind both the market and even the discretionary mutual funds they were supposed to displace.  This is awful. Not even the appliance of science can rescue active managers. What is the problem? Mezrich has some detailed and fascinating ideas, but his key point is that quant calls about which stocks will outperform are linked to macro calls about the economy and the movement in rates; and the quants, wittingly or otherwise, have made some very bad macro calls in the post-crisis decade. In particular, investing in value tends to be a bet on a strong recovery (when stocks which are too cheap can catch up), and is also a bet on higher interest rates. As this chart from Mezrich shows, patterns in quants' performance have followed rates.  Should quant equity managers feel bad about getting their macro calls wrong? Not so much. For macro hedge fund managers, I would submit that little or nothing could be more depressing than the following chart:  The white line is Hedge Fund Research's HFRI index of macro funds. The blue line is a popular exchange-traded fund investing in cash, and the purple line is an ETF investing in long-dated bonds. Macro funds exist to predict and exploit turns in the macro-economy and in global markets. And in the last decade they have, in aggregate, perpetually bet on a turn up in bond yields and a turn down in bond returns. The result is that, in aggregate and after fees, they have barely beaten cash. If you are a macro fund manager, that must be very, very depressing. Better luck next decade. Getting Brexit Done Some brief notes on the fallout from the British election. Investors are happy, it would appear, because suddenly the mid-cap FTSE-250 is outperforming the S&P 500 for the year:  There is good reason for this, because British stocks were previously trading at a steep "Brexit discount." The following chart shows the spread between the S&P 500's prospective P/E and that of the FTSE-250. Since the referendum year of 2016, the discount has been steep:  Plainly, there is space for that valuation gap to correct further. But it would be unwise to expect this rally to carry on much longer. There is plenty of uncertainty to come as Boris Johnson tries to nail down a free trade agreement by the end of next year. If reports that he is intent on legislating to prevent any chance of extending that deadline are true, then there is every chance of another year of brinkmanship in 2020. The differences would be that this time the players playing brinkman would be the U.K. and various EU interlocutors (many of whom will want different things from their future trading relationship with the British), rather than different factions within parliament. If a deal cannot be hammered out by the end of the year, the default will be to move to the basic tariffs dictated by the World Trade Organization. That would be a catastrophic worsening of the terms of trade for British companies. So some Brexit discount will have to persist. Authers' Notes It has been fun trying to organize a Bloomberg book club this year. If you haven't caught up with it, we have a big review of all the five books we set this year, and the conversations we had about them online and on the terminal, here. Please read! I have some requests. If you have any book titles to suggest for next year, send them to me. You can comment on this piece online, or send an email to the book club's address — authersnotes@bloomberg.net. And if you have any bright ideas on how we could improve the club, please send those also to that address. And now, to the book we will discuss next month, Hyman Minsky's hugely influential John Maynard Keynes. It isn't a book about Keynes, in reality, but more a book that explains how the 2008 crisis happened, decades before it did. For a summary of the deceptively complex theory that Minsky lays out, try this passage from Robert Barbera's The Cost of Capitalism: First, the persistence of benign real economy circumstances invites belief in its permanence. Second, growing confidence invites riskier finance. Minsky combined these two insights and asserted that boom and bust business cycles were inescapable in a free market economy — even if central bankers were able to tame big swings for inflation. Was Minsky right? Please read John Maynard Keynes or The Cost of Capitalism over the holiday period, and then Barbera will join us for an online discussion. Enjoy your reading. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment