Conspicuous consumers Keep an eye on American consumers. Everyone else is. As we enter the last month of 2019, and prepare to enter the last year of the U.S. presidential cycle, consumers attract attention for at least three reasons: - Their robust health is keeping the global economic expansion going, almost single-handedly

- We know from the experience of 2008 that over-extended U.S. consumers can mean global disaster

- In an election year, the health and optimism of the consumer could help to decide a close-run presidential race.

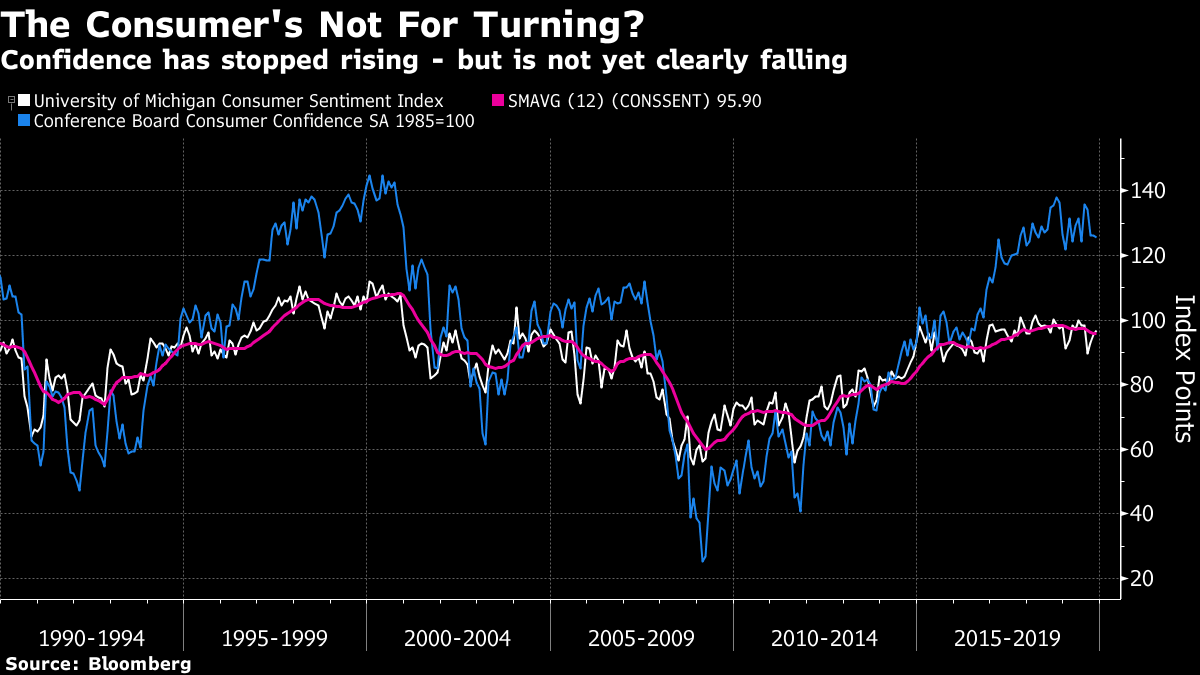

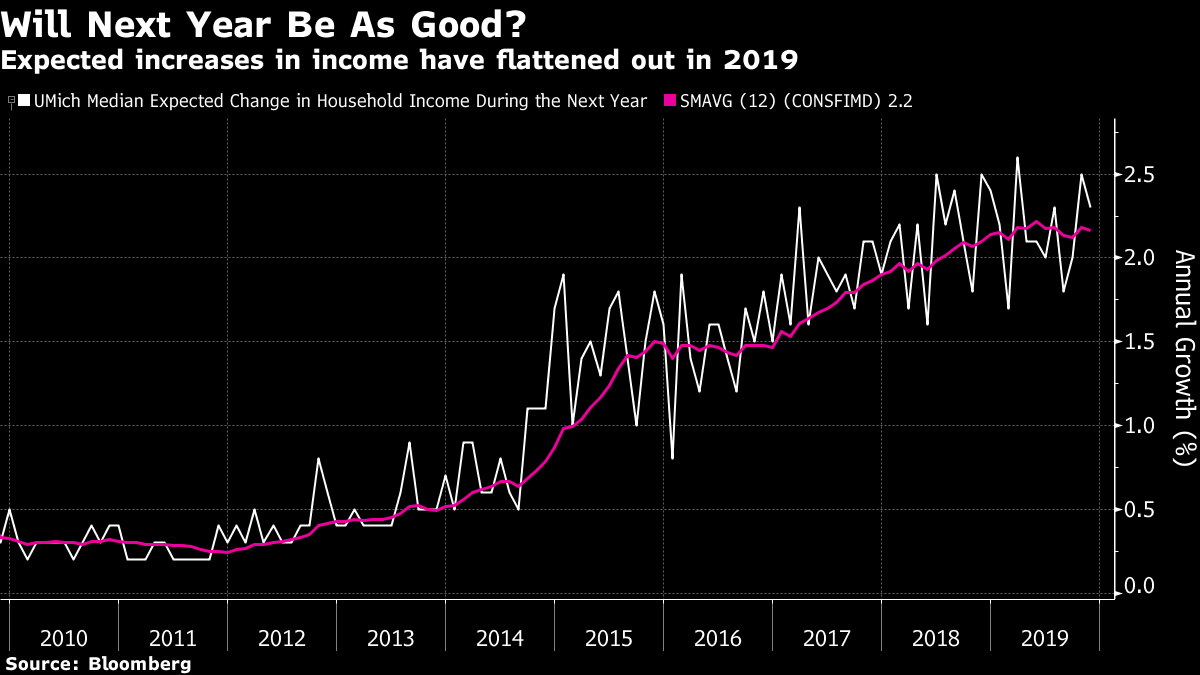

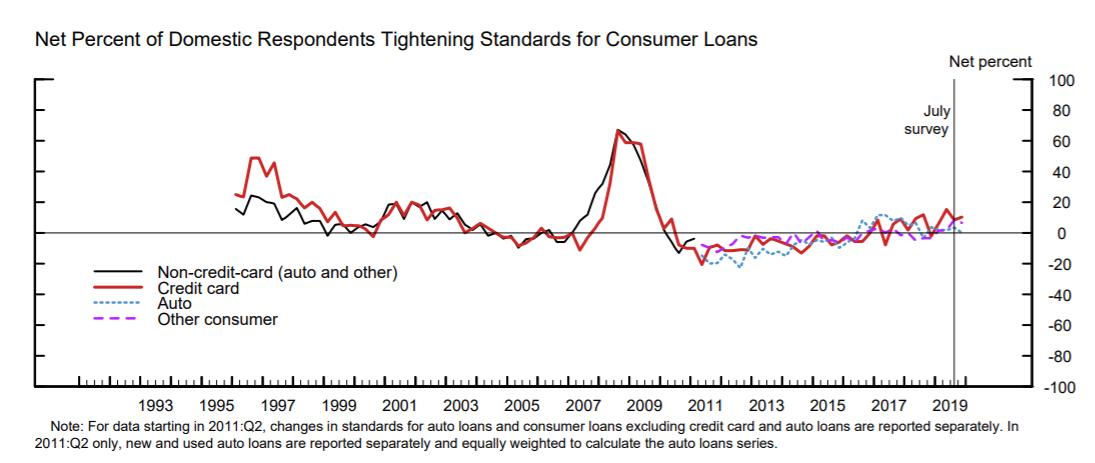

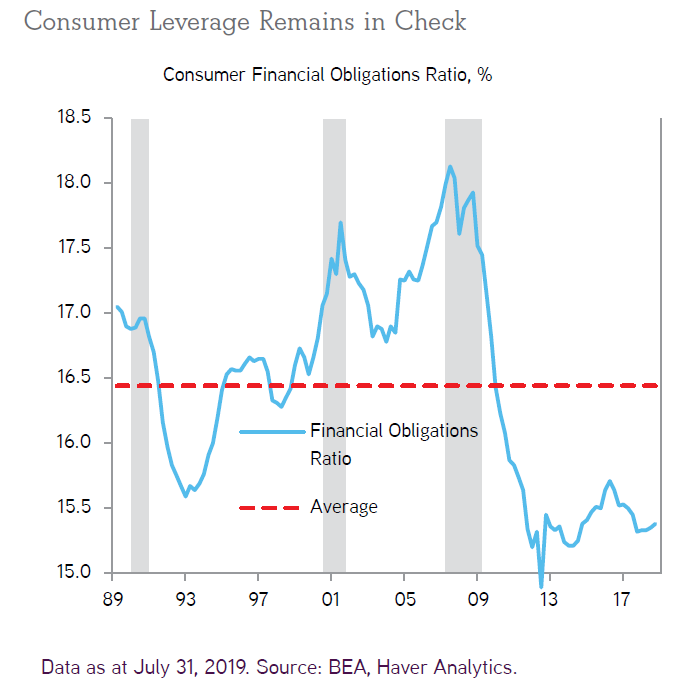

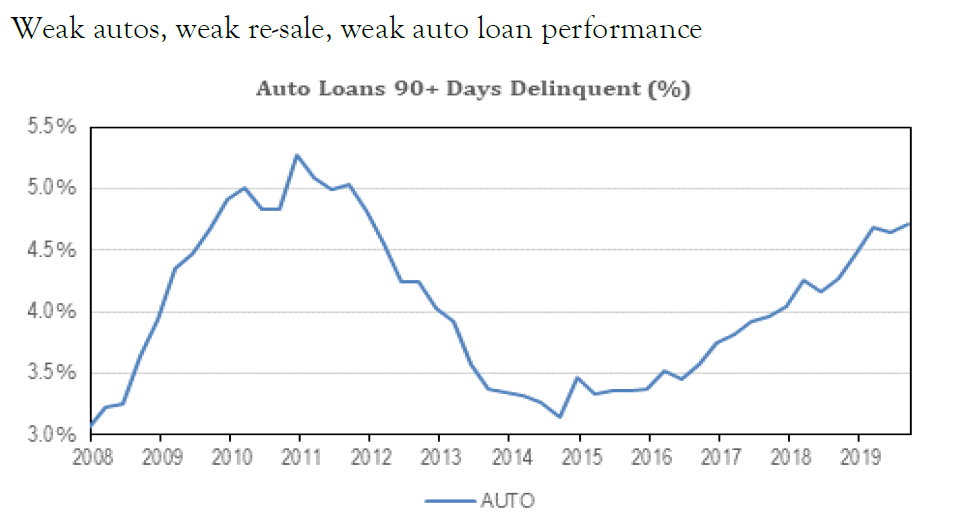

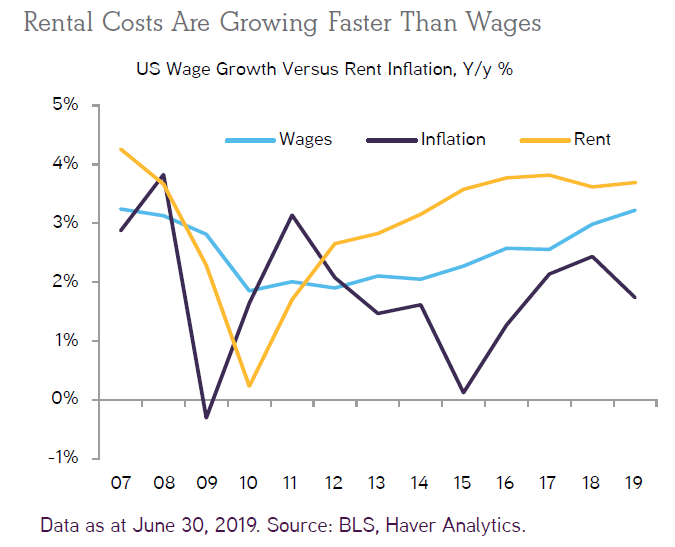

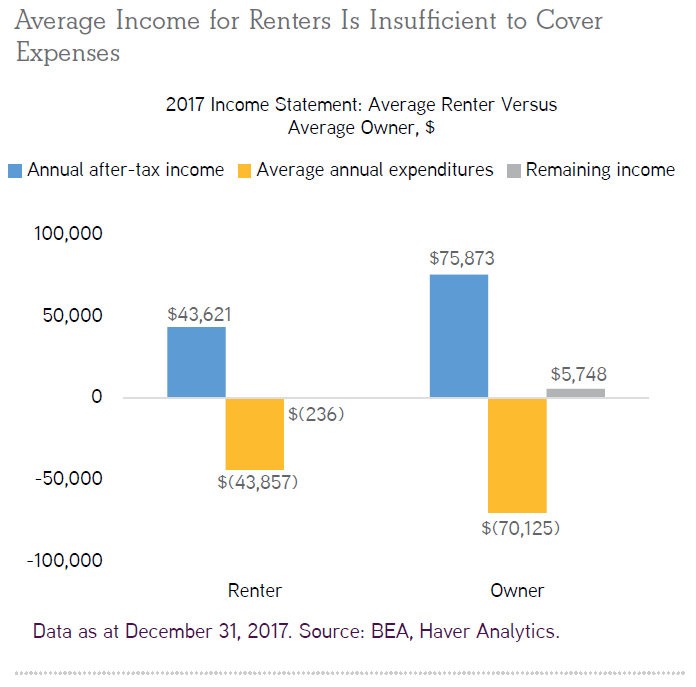

So where are we? The first and most important point is that consumer confidence remains high. But in economics what matters most is what happens at the margin — and so the second most important point is that confidence, according to both of the most widely followed surveys, produced by the Conference Board and the University of Michigan, has stopped rising:  What it is yet to do is start to fall. If this happens in a significant way (and we can see that the 12-month moving averages of both series are beginning very gently to point downward), then the odds for next year's presidential election would also start to shift significantly, away from President Donald Trump. But this hasn't happened yet. Will it? There is at least one element in the Michigan survey that counsels caution. Michigan regularly asks consumers what increase in income they are expecting over the next year. This is what a chart of the last 10 years looks like:  This took a long time to start recovering after the crisis. Hopes for wage increases had just begun to pick up as Barack Obama won re-election in 2012, but they then stalled and fell slightly, albeit from a higher level, shortly before Hillary Clinton failed in her bid to succeed him in 2016. It has stalled again. If the job market continues to tighten and put upward pressure on wages (and we have the last non-farm payrolls report of the year to look forward to this week) then optimism about incomes should continue. If not, not. As for the impact on the election, it will probably be decided, like the last one, in a small number of "battleground" or marginal areas of highly contested states. So what we really need to know about is income growth there. And for that, look at fascinating detailed work by Bloomberg data visualization, which you can find here. It shows that the areas of the country that have had the best improvement in income since Trump took office are disproportionately in "battleground" states. So that looks good for Trump. What of the risks of a crisis? Everyone's perception is unavoidably skewed by the recent memory of the last time the U.S. consumer grew over-extended. We know that a credit crunch for them can cause disaster. In that connection, the latest senior lending officer survey by the Federal Reserve isn't encouraging. It shows that the number of banks tightening standards for credit cards and auto loans is now clearly outnumbering the number of banks loosening.  This suggests that the consumer cycle should be approaching its end. But it isn't, as yet, showing anything like the aggressive squeeze on credit that happened before and during the last crisis. Further, the consumer balance sheet looks reasonably healthy, certainly by comparison with the crisis era. This chart was produced by Paula Campbell Roberts, director of global macro and asset allocation for KKR & Co. The financial obligations ratio — household debt payments as a proportion of total disposable income — remains well under control by recent historical standards.  Further, if we look at consumer delinquencies, we again see a healthy picture, which should have been improved by this year's three rate cuts from the Fed:  The rate of improvement has slowed a little, but it would be absurd to see any great sign of trouble or risk of impending crisis in these numbers. In aggregate, the U.S. consumer is far too healthy to raise any concerns of a repeat of the last great crisis. Now for some exceptions: Delinquency rates for autos don't look healthy at all. They are their worst in seven years. This chart is from Deltec Bank & Trust Ltd., and makes the point clearly enough:  Deltec describes this as the most visible deterioration of credit in the cycle, which can be attributed to weak demand for cars. This is an important sector for the U.S., and signs of ill health here cannot be ignored. One specific issue may make the consumer harder to judge. One of the legacies of the GFC has been a rise in rentership, with about 36% of American households now renting rather than owning — up from about 30% pre-crisis. Obviously, many are in the millennial generation, and unable to buy thanks to the demands of repaying debt and the escalating costs of buying in urban areas. As it is, according to a great study by Campbell Roberts of KKR, we find that rents are rising faster than wages:  That is a big problem, because renters — unlike owners — are already unable to cover all their costs with their income:  The growing share of renting in the economy won't go away. Higher house prices almost guarantee that it will intensify. In combination with the huge cost of student debt, which is proving to be a big political issue, higher rents and higher numbers of people paying them are part of an important shift in the economy. American consumers are asset-light these days, as Campbell Roberts puts it. If things go wrong, they don't have equity in a house to fall back on, and the chances are that their high rents have thwarted their hopes to invest more in the stock market. So to answer the questions that are preoccupying investors — the U.S. consumer stays strong, although there is reason to expect that strength to slacken; there is little reason to fear a crisis on anything like the scale of the last one, but there are plain signs of danger in corners of the market; and this measure like so many others suggests that next year's election is too close to call. ICYMI There were some technical problems at the end of last week, and so I gather some readers failed to get this newsletter via email. I apologize for this. In case you missed them, you can find Thursday's newsletter, on U.S. investors' reasons to be thankful, here, and Friday's newsletter, on the pitch invasion at this year's Yale-Harvard football game and what it tells us about ESG investing, here. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment