Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter wondering how the divorce between Jerome Powell's rhetoric and the Federal Reserve's projections can be amicably resolved. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

Dancing Queen

Christine Lagarde had her debut on Thursday with her first press conference as president of the European Central Bank. And, as expected, she didn't stick just to monetary-policy. Lagarde said that exercising freedom to speak about fiscal policy was necessary because "it takes many to actually dance the economic ballet that would deliver on price stability but also employment and growth."

It takes two to tango, but three for Lagarde's ballet: monetary policy, fiscal policy and structural reforms.

Assessing the ECB chief's message and the market reaction to it, along with the same exercise for Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell's press briefing this week, showcases some deeply ingrained perceptions about the global economy.

Policy levers aren't being pulled in a synchronized fashion so as to adequately boost aggregate demand, as Lagarde flagged. Because of this, structural disinflationary forces are expected to be the dominant feature of the macroeconomic backdrop, a point that Powell made in his comments Wednesday.

Hence 10-year U.S. inflation breakevens only pared about half their pre-Powell retreat after he basically dared breakevens to rise by reiterating a higher tolerance for inflation.

Inflation caps and floors show that the recovery of inflation breakevens off their lows of the year is being driven by receding fears that inflation will average persistently below 2% (associated with a global downturn) without much in the way of a corresponding increase in concern that inflation would average above 2% over a five-year time-frame.

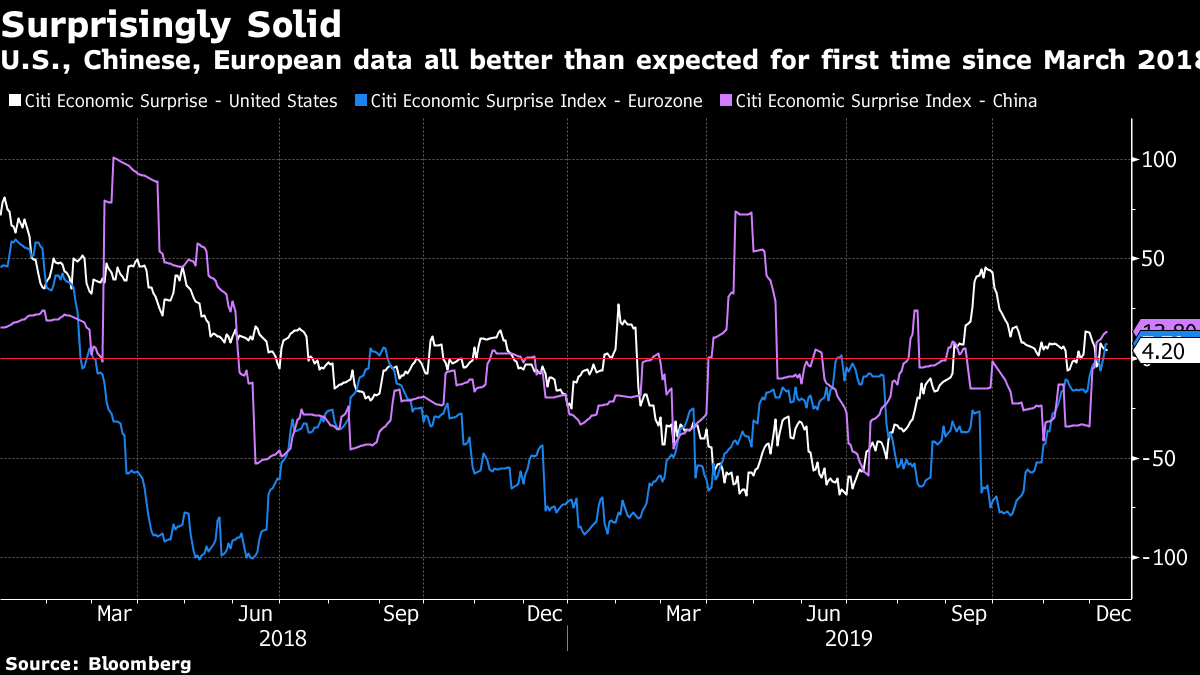

Lo and behold, despite a fairly steady drumbeat of positive newsflow, 10-year Treasury yields are virtually unchanged from where they were a month ago: about 1.9%. That's despite news on President Donald Trump signing off on a deal averting a Dec. 15 tariff hike on China, and better than expected activity from the world's three major economic areas.

The deafening silence of fiscal policy and the lack of coordination on pro-growth policies may help explain why so many investors have faith that the music is still playing for sovereign debt.

For bonds, the message is simple: beware the ballet.

Rave Reviews for Powell

There's no doubt about it: the market believes Powell was dovish.

Inflation-adjusted five-year yields tumbled and the dollar sank as he made the case for Fedwatching getting very boring: that is, rates remaining on hold for the foreseeable future.

The Fed's dot-plot projections didn't show a 2020 hike, as some had feared, and markets are still pricing in the potential for easing, not hiking, in the year ahead.

But a question lingers: how much of Powell's dovishness is structural rather than cyclical?

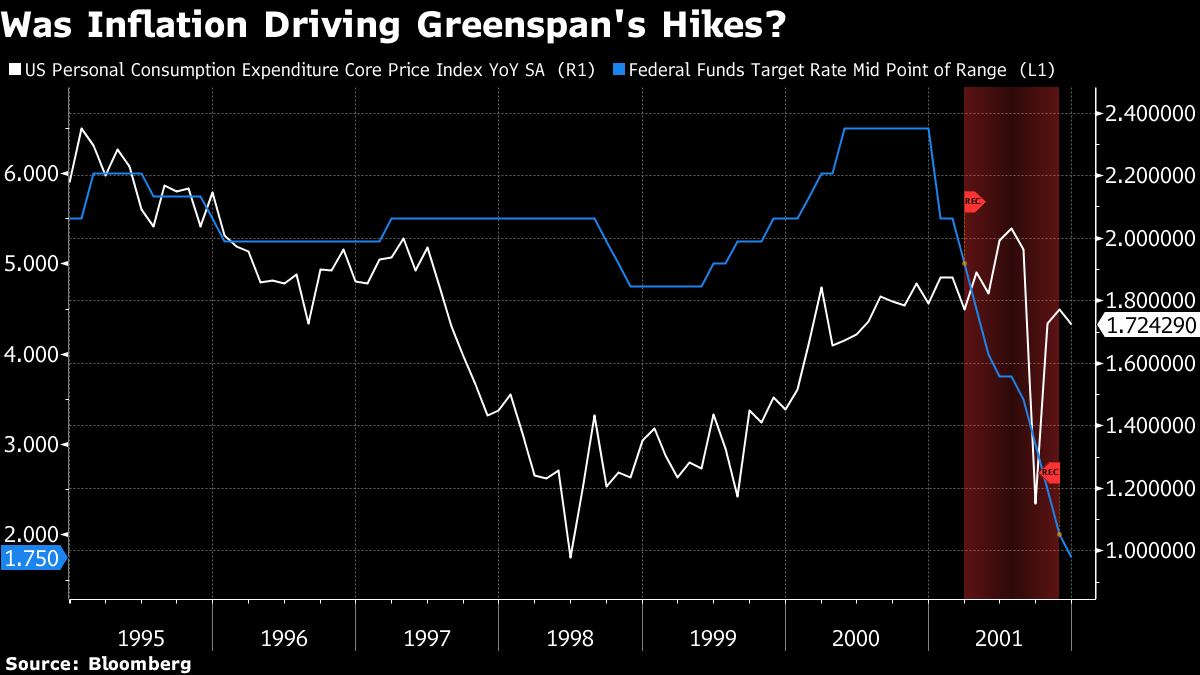

The Fed chair argued that unlike the mid-cycle adjustments in the 1990s (and particularly the final one, after which the central bank resumed rate hikes in relatively short order), there will be less of a need to raise rates going forward. That's because "we've learned that unemployment can remain at quite low levels for an extended period of time without unwanted upward pressure on inflation."

It's unclear that data were screaming for rate hikes to control inflation back when Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera's debut albums were topping the charts. Core PCE inflation was running below 1.5% when the tightening cycle resumed, and peaked at just over 2% in 2001 during the recession – when the Fed had already been cutting rates.

Powell himself said he would want to see inflation "that's persistent and that's significant" before raising rates. That doesn't quite square with the Summary of Economic Projections, which indicates a return to tightening in 2021 with the PCE inflation measure at 2% to 2.1%.

He explained the discrepancy by saying, "so I think what may be behind some of that is just the thought that, over time, it would be appropriate – if you believe that the neutral rate is 2.5% – it would be appropriate for your rates to move up in that direction." The neutral rate, also known as r-star, is the theoretical level of the policy benchmark that leaves the economy neither too not nor too cold.

That does not sound like the thinking of Fed officials who are fundamentally reevaluating their policy formulation framework and reaction function.

Members of the Fed's Open Market Committee don't regard an unemployment rate below 3.5% – the current level – as sustainable over the long haul without sparking excessive inflation. Put differently, the typical monetary policy maker, in effect, thinks a higher share of people who want a job need to be unemployed in order to achieve the inflation part of the dual mandate.

Yet in the press conference, Powell came off – and deservedly so – as a job-crusader. He said slack was still evident even with the unemployment rate at 3.5%, citing relatively muted wage gains as evidence that the labor market isn't yet "hot."

Powell's rhetoric, juxtaposed against the FOMC's assessments, speaks to a conflict between the Fed's near-term view and its medium-term operational framework. While he may be seeing the world without gazing at the (r and u) stars, it's not clear that the rest of the committee is quite there just yet. And lowering estimates for the natural rate of unemployment (u-star) dramatically – rather than just inching them lower – could imply the need for lower interest rates.

It was easy to be dovish when U.S. activity was softening, global activity was deteriorating, the yield curve was getting more deeply inverted and the U.S.-China trade war was escalating. But it may be tougher to secure change at a major institution with a rich academic foundation, all the more so as these headwinds abate.

That leaves the risk, though perhaps not the base case, that people read too much into Powell's dovishness – erring in much the same way the central bank does when it raises its estimate of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment after every downturn: mistaking a cyclical shift for a structural one. Without a pickup in inflation, however, the point could well be moot.

Post a Comment