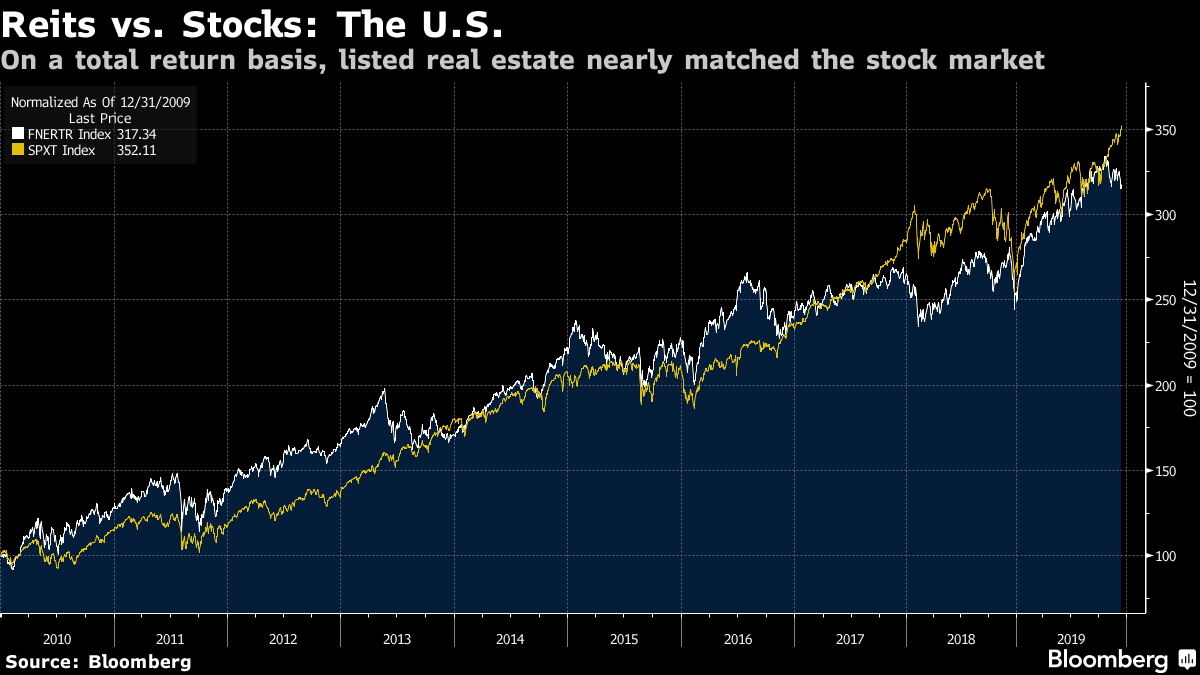

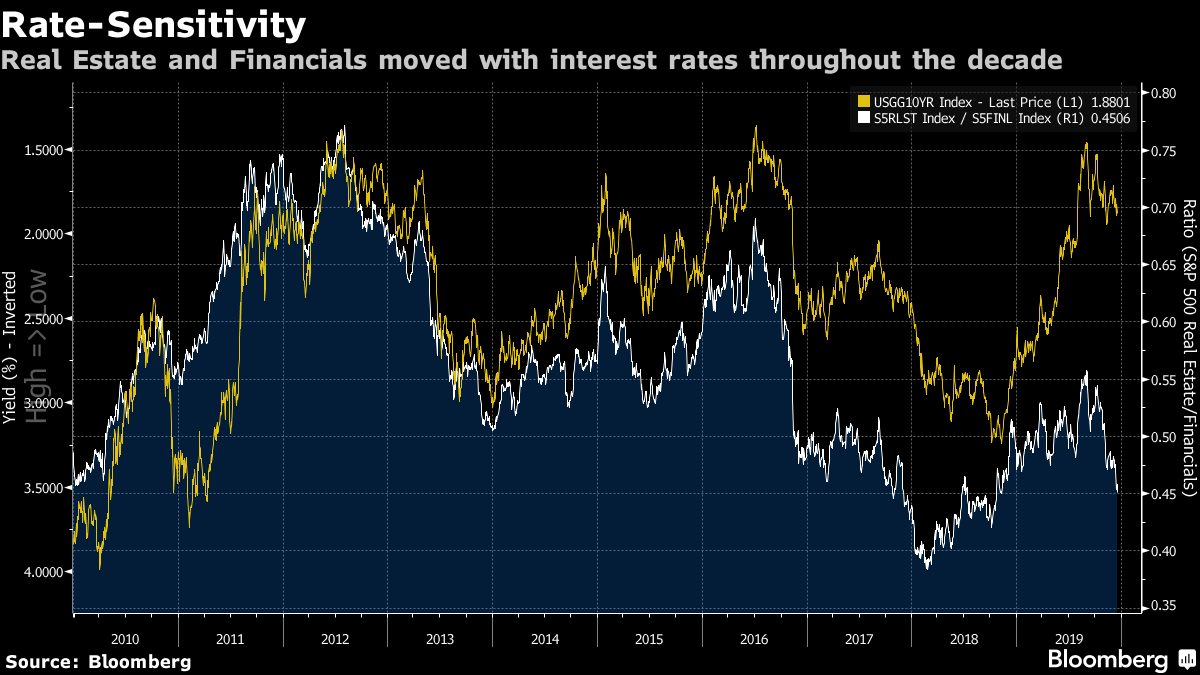

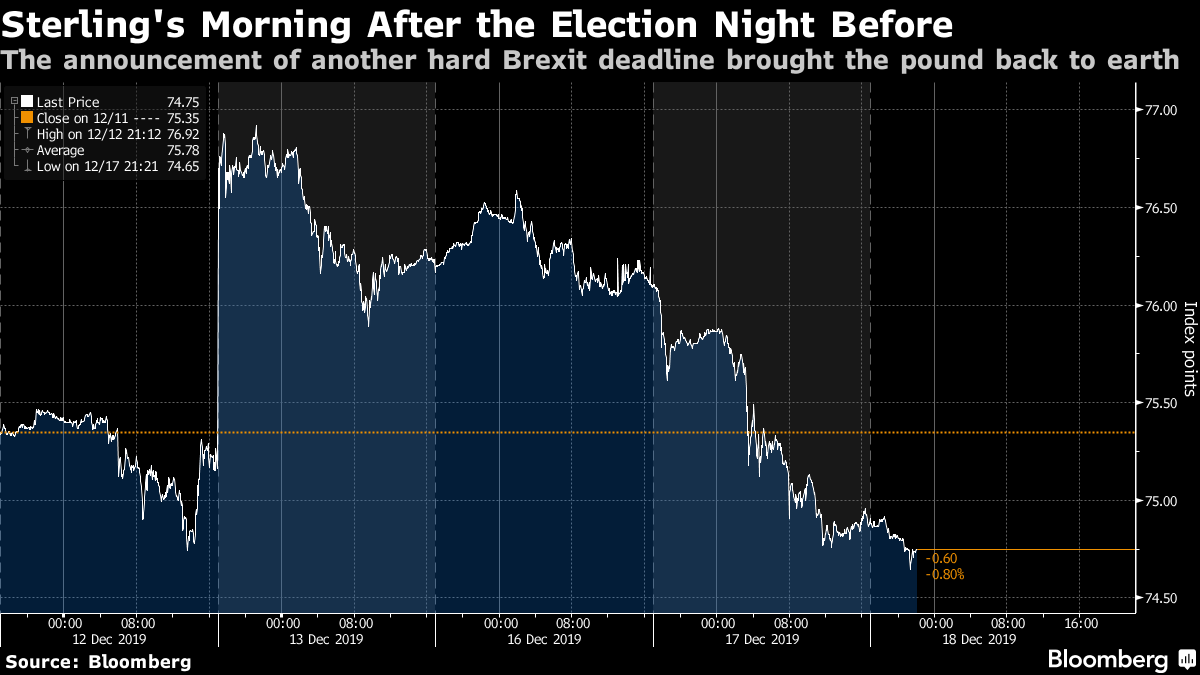

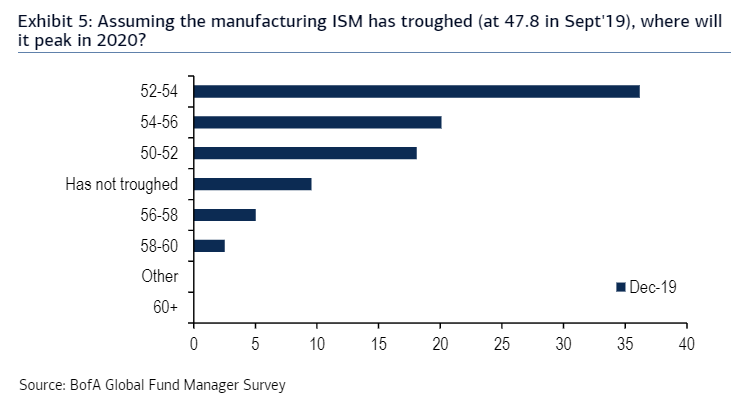

The 20-Teens: They've Been Real At the outset of this decade, there was a wide belief in "realization" — moving toward real assets as central banks printed money. The argument, perhaps most famously expressed by JPMorgan Asset Management, was that real assets could hold their value in the likely event of inflation. For big pension funds and endowments, investments in infrastructure, property, or even farmland seemed very appealing. They offered a way to exploit such investors' key advantage; their ability to withstand illiquidity. At the end of the decade, inflation has failed to reappear, and interest rates have remained very low. But realization hasn't fared all that badly. Lack of infrastructure continues to bedevil the world. Big Keynesian spending on improving the dilapidated fabric of the U.S. might be justified on purely practical grounds, and two successive presidents have set out with the aim of improving infrastructure — and failed to achieve it. Despite all this, sinking money into infrastructure would have worked out OK. This chart shows the total return on S&P's global infrastructure index, which includes 75 large listed groups from around the world, compared to the MSCI All Countries World index. Infrastructure has held its own:  One asset class to benefit from this in a big way was listed real estate. But its performance has been strong for almost exactly the opposite of the reasons that were being proposed by real asset bulls 10 years ago. We all know that U.S. large-cap stocks have had a great decade. But if we compared them with real estate investment trusts on a total return basis, we find that REITs kept up the pace almost all decade long. Conservative investors who sheltered in real estate due to the safety of the rental income and the underlying asset found themselves enjoying almost the full returns of an equity bull run:  Beyond the U.S., the effect is more pronounced. Stocks have fared less well beyond American shores, but the same isn't true of real estate. As a result, REITs have fared considerably better than stocks across the world over the last decade.  People who made this investment were often right for the wrong reasons. Real estate was intended as a hedge against inflation. Over history, it is often positively correlated with interest rates. After all, real estate is much aided by a strong economy, which boosts rents and occupancy rates. Rising rates are generally a sign of economic health. Real estate investors understandably grow peeved at the suggestion that REITs are only a play on rates. However, over the last decade, the entire stock market has turned into one big play on interest rates. REITs, with the attractive cash flows they offer from rental income, rise when interest rates are falling, and grow less attractive as rates increase. The opposite is true of banks, as it is harder for them to profit when rates are low. As a result, these two sectors have functioned as almost perfect plays on interest rates throughout the decade: Bet on REITs to outperform banks when rates are falling, and banks to beat REITs when bond yields are rising.  After such protracted strong performance relative to the market, and with a number of commercial property markets looking over-built, the next decade might not be so good for real estate. But everyone has some cause to hope that extreme sensitivity to interest rates goes away, and that some of the original reasons for "realization" recur. What Could Possibly Go Wrong? At moments of brimming optimism, it is always good to ask this question. The freshly elected prime minister of the U.K. gave us one good example by announcing that he would legislate to bar himself from asking for an extension to the deadline for agreeing a trade deal with the EU. That deadline comes at the end of next year, and few people if any believe it is realistic to hope for any good settlement in such a short space of time. The linkages are too close and too complex, and the scale of the different interests too diffuse to allow for a quick negotiation. If no deal is reached by the end of next year, then the U.K. and the EU start trading with each other on minimal World Trade Organization terms, having previously been part of a single market and a customs union. This means that a repeat of last year's brinkmanship over the possibility of a "no-deal" outcome is in prospect. Boris Johnson does have some wiggle room on this, thanks to his large majority. This isn't such an alarming outcome as the risk of leaving the EU without a deal on anything, which haunted 2019. Such risks as sudden stops to air traffic control or provision of medicine should no longer arise. But moving from a single market to WTO terms with by far its biggest trading partner would still be very damaging to the British economy. As a result, what Johnson gave to sterling with his election victory on Thursday night, he took away with his trade announcement on Tuesday morning:  Many analysts, myself included, had thought that the scale of his victory would free him to make a broader and "softer" Brexit deal, in line with the wishes of many of his party's new northern voters, many of whom badly need a generous trade agreement to safeguard the British auto industry. Apparently we were wrong. What else could go wrong? The latest Bank of America global survey of fund managers finds them in bullish mood to approach the end of the year, and having dodged plentiful bullets during 2019. If there is one key thing that could yet go wrong, it could involve the manufacturing sector. About 90% of fund managers believe that the bottom is now in on the ISM manufacturing survey:  For the record, the manufacturing PMI for the U.S. hit 47.8 in September, and its most recent reading was 48.0. This came before the news that Boeing Co. would stop production on its troubled 737-Max which could easily, on its own, bring the PMI below 47.8. There are good reasons to believe that U.S. manufacturing has reached a trough, and these are fortified by the avoidance of further tariffs between the U.S. and China. But investors seem to be allocating money as though a manufacturing recovery is a fait accompli . It isn't. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment