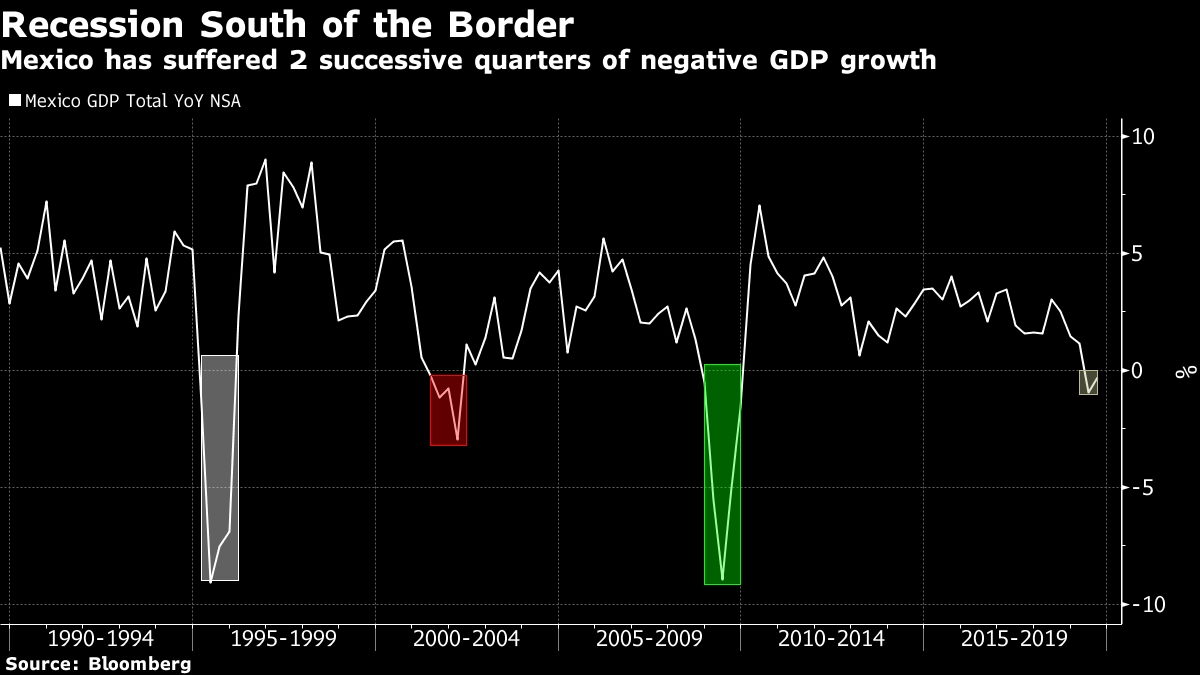

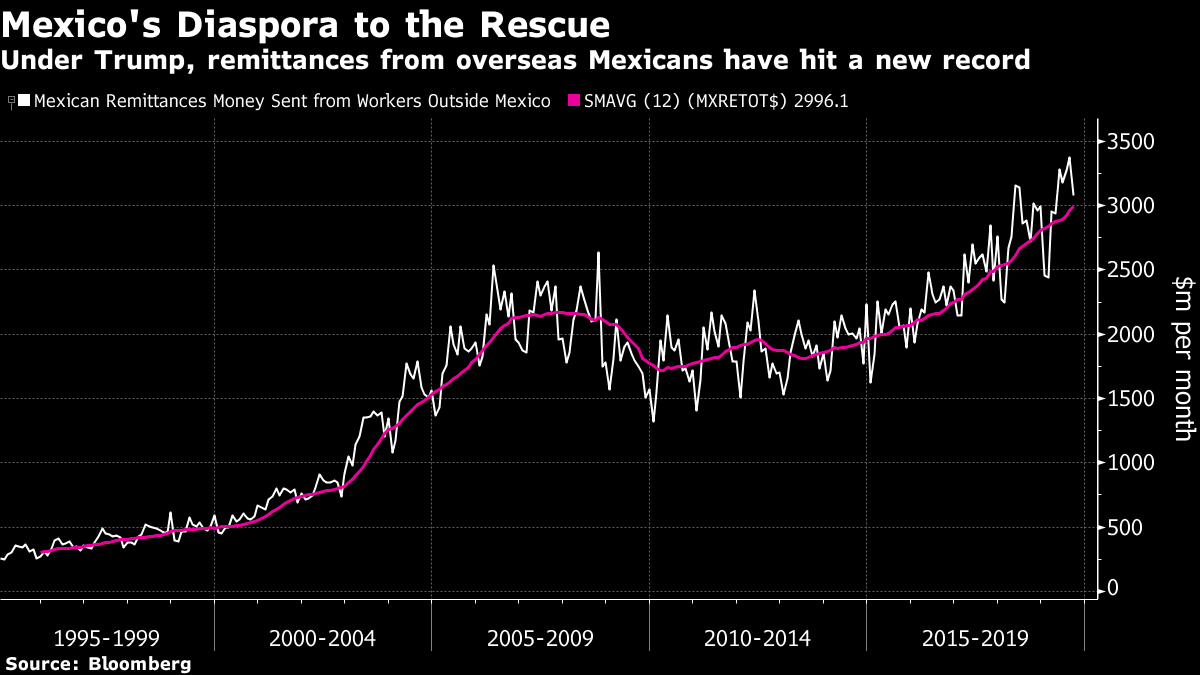

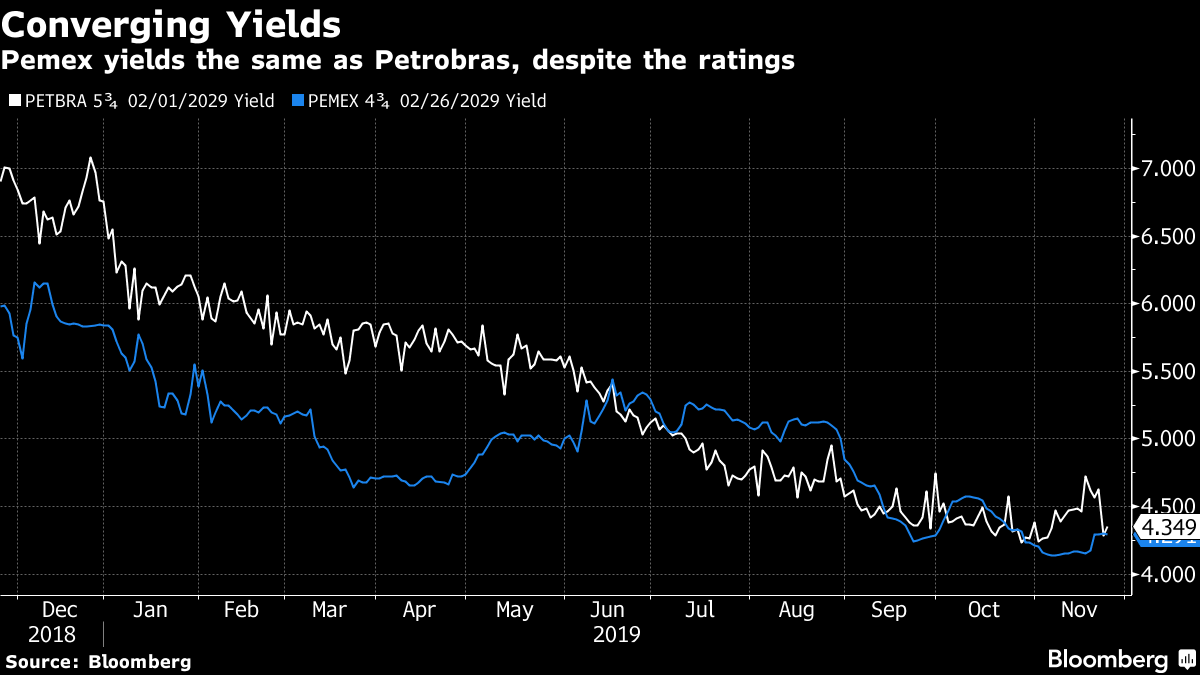

Recession Almost Reaches the U.S. Recession is very close to the U.S. In fact, it couldn't be closer. Mexico is now technically in recession. By Mexican standards, this isn't yet a serious contraction. And by anyone else's standards, two quarters of marginally negative growth seem relatively painless. The country suffered vastly worse economic convulsions after a botched devaluation sparked the Tequila Crisis in 1994, and again after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008:  Since the Tequila Crisis, however, Mexico's economic cycle has been very much in sync with the U.S. to the north. This has been an advantage for much of the time. Even though it is a big petroleum producer, it hasn't joined other emerging markets in following the commodity cycle up and down. Instead, like the U.S., it suffered a minor recession at the beginning of the last decade, and a major one at the end of it. Both were very much generated by the U.S. itself. Mexico's economy has integrated enough with the U.S. since 1994 — which began with the start of the Nafta trade treaty — to avoid some of the worst cyclicality and volatility of other emerging markets. But it hasn't diversified enough to be able to keep growing when the U.S. hits trouble. And this raises a question: Is Mexico's minor slump a harbinger of a recession in the U.S.? It might well not be. First of all, one of the strongest factors in Mexico's favor is the strong flow of remittances from migrant workers outside the country, the great majority of whom are in the U.S. Remittances had stagnated for years, but have taken off under Trump to hit new records. This isn't because of an influx of new migrants, and instead suggests that decent paying jobs are much easier to find now:  And while the Tequila Crisis was sparked by the Federal Reserve's surprise decision to hike rates during 1994, which put pressure on the Mexican peso when it was still pegged, in the past year the Fed has been easing. That relieves pressure on the currency. Judged in real effective terms, taking account of changes in inflation, we can see that the peso has stayed stable during the ugly headlines and tweets of the Trump era. While weak, there is room for it to depreciate further:  Meanwhile, other things in the Mexican economy have gone awry. Petroleos Mexicanos, the state-owned oil company known as Pemex, has for decades been the milch cow for the government, allowing the country to survive low levels of tax collection. But with the new left-wing President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, or AMLO, determined to maintain fiscal discipline, reporting by Bloomberg News shows that the oil company has had to resort to delaying payments to suppliers and contractors. Any such sign speaks directly to the creditworthiness of Mexico as a whole. Meanwhile, Sebastian Boyd pointed out in the following chart that Brazil's national energy company, Petroleo Brasileiro SA, or Petrobras, now trades at the same yield as Pemex — despite having been mired in scandal for years and having a significantly poorer credit rating:  The issue of Pemex is wholly indigenous to Mexico. If it loses the confidence of investors, it is hard to blame that on the Americans (tempting as that may be for many Mexicans ). Meanwhile, the gap between Mexican and Brazilian sovereign bond yields has also narrowed, despite Brazil's severe problems of recent years.  Given that Brazil's sovereign debt is rated several notches lower, this suggests that Mexican debt might be decent value — if only because it shows very low market confidence in the country. As the Tequila Crisis demonstrated a quarter-century ago, loss of market confidence can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, so this is still alarming. But there is one other critical area of hope for Mexico. The central bank has kept interest rates high, in a largely successful attempt to defend the peso and contain inflation. Now, with inflation sinking, real overnight rates are their highest in a decade. There is room for far more easing of monetary policy from here:  That room is needed. This is still only a minor slowdown. But consumption is slowing, and the U.S. election, combined with the unfolding story of the AMLO presidency and Mexico's continued terrifying battle with the drug cartels (who are fueled by the insatiable American appetite for drugs), will all stoke further uncertainty. Those optimistic about Mexico also have to contend with the uncomfortable fact that it's likely to be hurt by any resolution of the trade conflict between the U.S. and China. It lost many manufacturing jobs to China when the latter joined the World Trade Organization, and there had been hopes that they would return. Any recession in Mexico, technical or otherwise, will always reveal some problems or mistakes by the U.S. But this latest slowdown appears to say more about problems of Mexico's own making, and about declining market confidence. Rise of the Acronyms I have never been a fan of acronym-based investing. As a rule, if someone thinks to apply an acronym to a group of investments, we can be sure that: - It is wildly oversimplified;

- It is recognizing a trend already under way, and so it is already too late;

- It will prompt the "suckers" to buy, causing a bubble and then a fall.

Exhibit a) is the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China). The acronym was coined by Jim O'Neill, then of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., in a report published in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks to suggest that the biggest emerging markets should start to exert more weight in international forums such as the G-7. He did not have investment in mind. Then it became an acronym. This is the exciting history of MSCI's BRIC index, compared to the developed world:  More recently we have had the FAANGs, originally named for Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Netflix Inc. and Google Inc. Subsequently, a few other companies have been crow-barred in, led by Apple Inc., while a blind-eye has been turned to Google's change of name to Alphabet Inc., as that would mess up the acronym. Here is the performance of the NYSE FANG+ index from its inception, compared to the S&P 500:  In general, if you wait for someone to come up with an acronym, you have probably left it too late. Which brings me to the political world. Apparently, there is now talk in Britain of a Government of National Unity, or GNU. For the uninitiated, a gnu is another name for a wildebeest. In Britain this animal is best know as the hero of The Gnu Song by the duo Michael Flanders (father of Bloomberg colleague Stephanie) and Donald Swann. But now a GNU also stands for the notion that Boris Johnson's Conservatives could be denied a majority in next month's general election, to be replaced by a coalition with someone other than Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn at its head. Tony Blair, the former Labour prime minister, has made clear that he thinks this would be a good idea in the face of "dysfunctional" politics, and that it would be possible to find "a suitable candidate to get the thing done." The implication is that Corbyn is unsuitable. At certain points this year, a GNU did look like a real possibility. But like BRICs and FANGs before it, the latest polls suggest that we have already passed the point of Peak GNU. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment