Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's worried the negative correlation between stocks and bonds has gotten a tad too intense. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

The Ties That Bond

The U.S. stock market has a dependency issue: it can't go up unless Treasury yields do too.

That's only a mild exaggeration. For the past two months, over 75% of days in which the S&P 500 has gained coincided with a rising 10-year Treasury yield. Prior to that, the year-to-date share of "stocks gain, yields rise too" was 55%.

Why August as a demarcation line? Well, it's when the 10-year yield cracked below 2% on the heels of the Federal Reserve's commencement of an easing cycle. It's also when investors began to really throw in the towel on the prospect for reflation over the next year, judging by the slimming spread between 10-year yields and the 10-year, one-year forward rate.

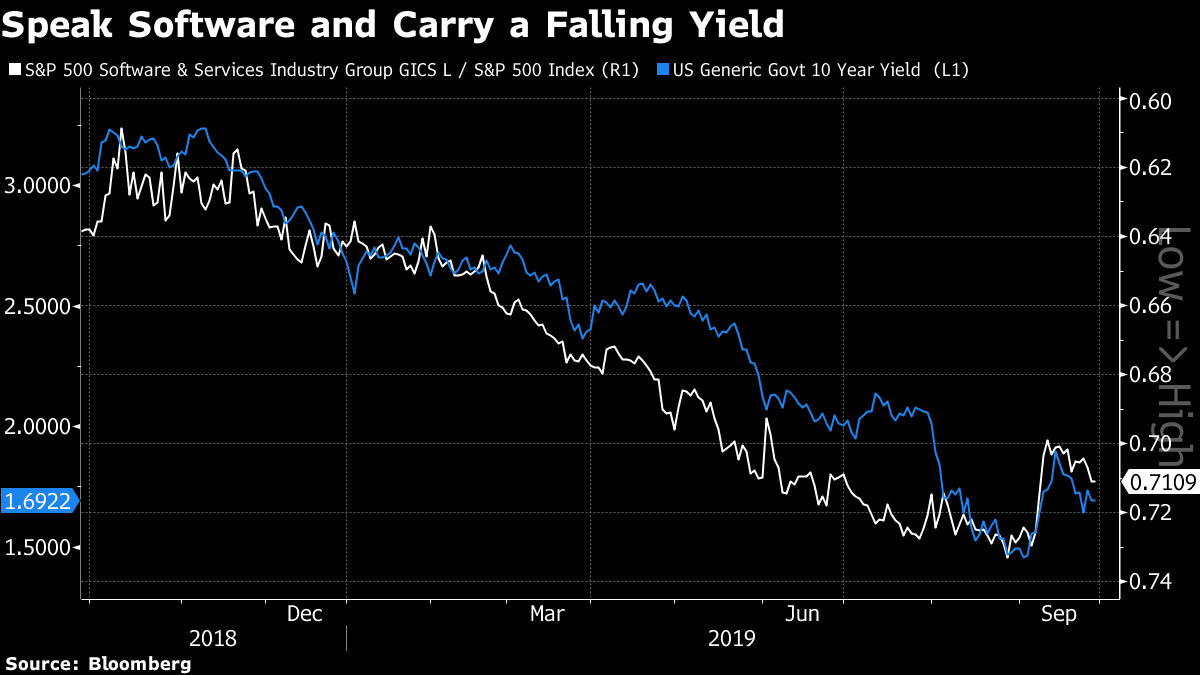

For software stocks – the most important contributors to the bull run – it's striking how much relative performance over the past year has been linked to bond-market dynamics. The thinking here is that falling yields reflect concern about future global activity, so stocks that have shown a structurally superior earnings profile (growth stocks, like software) are prized. Note the inverted axis for relative equity performance!

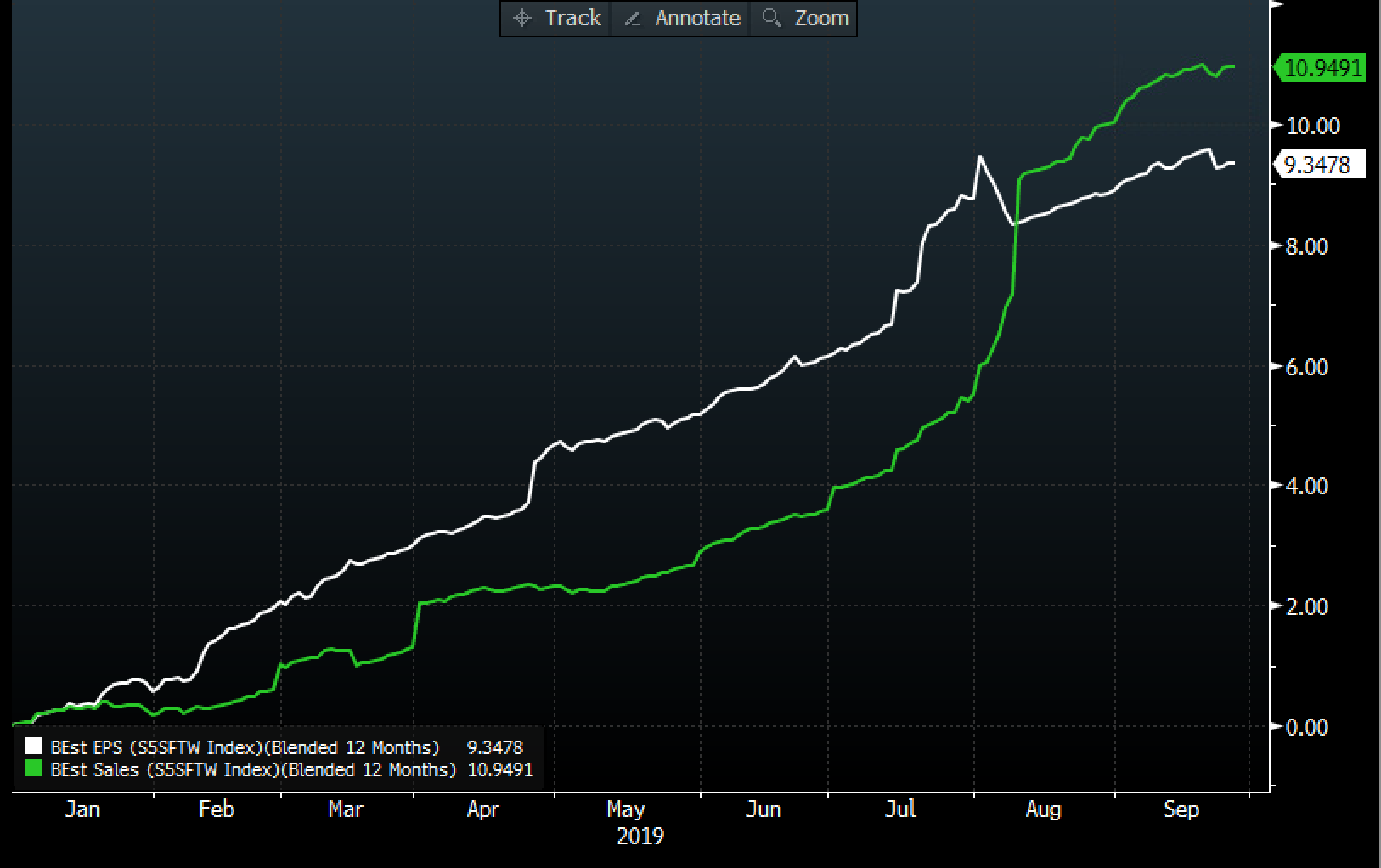

As such, it was particularly encouraging to see software stocks (as judged by the IGV ETF) bounce off their 200-day moving average on Wednesday – a session in which yields rose – to reverse substantial losses and ultimately outperform the benchmark gauge. If software (which happens to be the biggest industry group in the S&P 500) falters, it's difficult for the rest of the market to provide a sufficient offset. Especially as this segment of the market has seen earnings estimates buck the market trend and push ever higher.

If the equity market were to become a little more yield-agnostic, this would likely be a positive for risk bulls. Relying on rising yields to power the market higher amid a backdrop of deflating domestic confidence, an ongoing Fed easing cycle, an endless barrage of conflicting trade headlines, lackluster activity abroad, and now a potential impeachment of U.S. President Donald Trump would seem akin to swimming against the tide.

The story of 2019 for the 10-year yield has been a tendency to trade in 20-basis point ranges then knife downwards. This week is poised to mark the smallest change in over a month, despite elevated day-to-day volatility. Perhaps a period of Treasury yields consolidating as earnings season approaches will give stocks a chance to craft their own narratives.

Evans Keel

The big Federal Reserve news this week is that a purportedly dovish member of the committee isn't as dovish as you might've thought, which increases the chances of additional accommodation from the U.S. central bank. Sorry if that's confusing; bear with us for a moment.

Charles Evans, head of the Chicago Fed, revealed that he doesn't see the need for more easing this year, indicating that he sees inflation breaching 2% thanks in part to the two rate cuts delivered this year. Evans went along with a 25 basis point cut in July even though he had earlier indicated support for a half-point reduction.

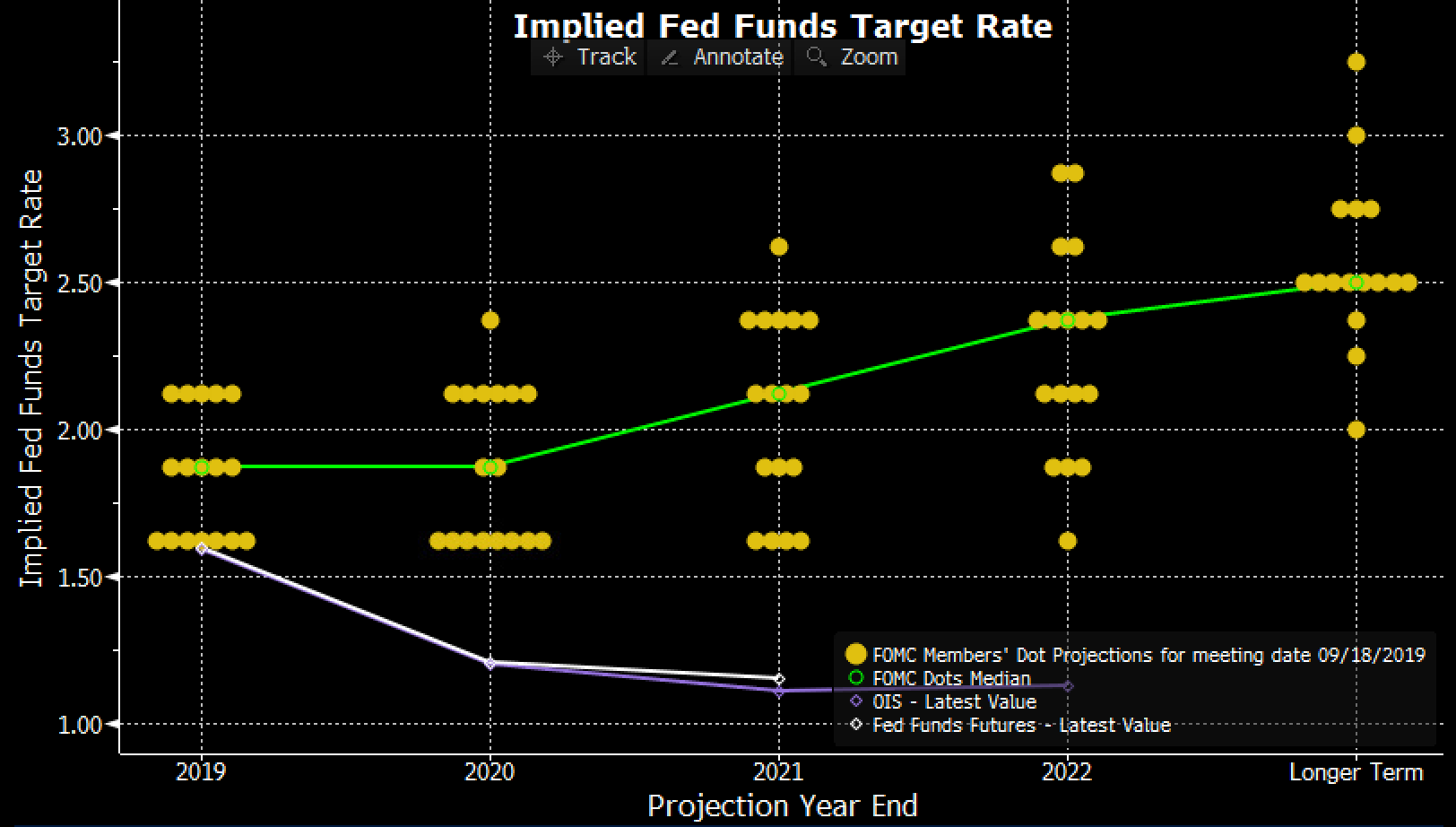

Why does this matter? Well, first let's do an as-vague-as-possible mapping out of the dot plot for the rest of the year to try to infer the likely Fed outcomes if financial conditions don't change too much, economic activity unfolds roughly according to plan, and trade tensions are neither heightened nor lowered.

Five officials think the Fed has already eased too much. That number includes Eric Rosengren and Esther George, based on their public votes against easing. And three of the following: Loretta Mester, Robert Kaplan, Patrick Harker, Raphael Bostic and Thomas Barkin.

Five officials think enough easing has been provided: Evans, two of the group above, and two more among the following: Mary Daly, John Williams, Randal Quarles, Michelle Bowman, Richard Clarida, Lael Brainard and Chairman Jerome Powell.

And seven officials anticipate another cut is warranted: James Bullard, Neel Kashkari, and five of the unassigned above.

(The Bloomberg terminal's "Summary of Recent Remarks" from Fed officials was instrumental in constructing this schematic)

The upshot: either the overwhelming majority of the board of directors, or a strong majority plus New York Fed President Williams, sees additional accommodation as the most likely outcome if everything goes according to plan.

This means the dot plot's inherent divisions may be over-hyped, and if Powell thinks another cut is appropriate – his comments certainly haven't ruled one out – then it won't be hard to build a strong consensus for such a course. In other words, the investors fleeing short-term bond funds may have been overly jittery.

Contemplating Credit's Cracks

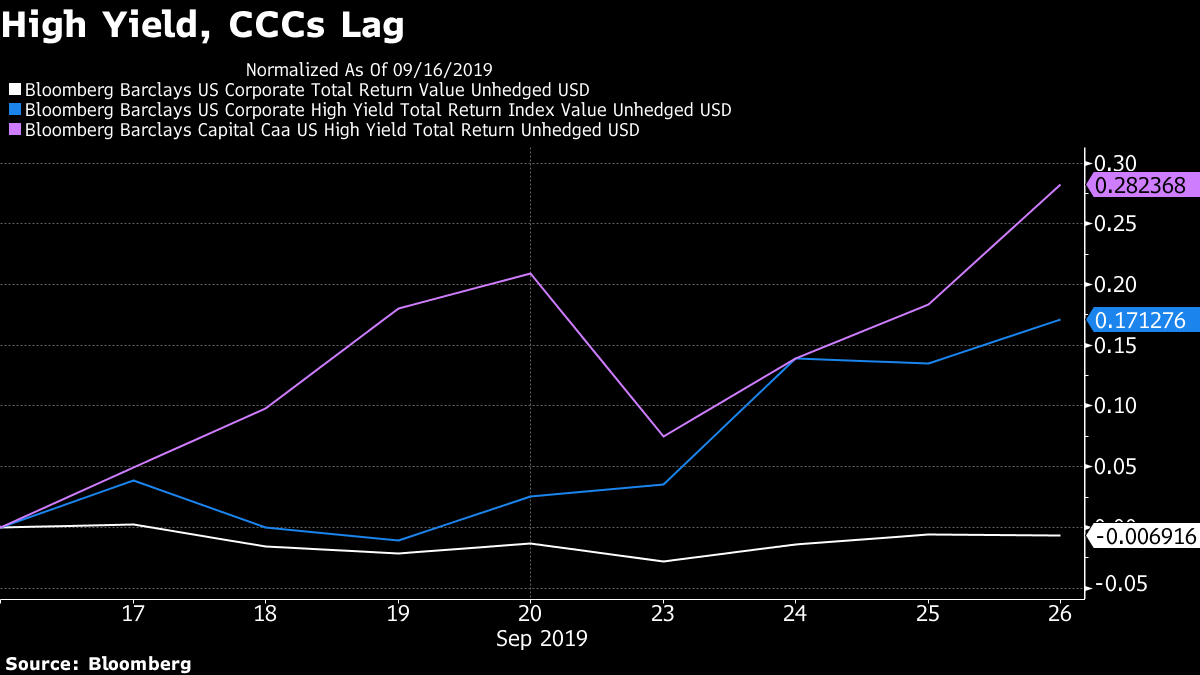

There's cause to be concerned about high-yield credit. Oaktree Capital's Howard Marks is cautious, for one. There's also cause for context that argues against ringing the alarm bells just yet.

Nearly $30 billion in high-yield debt has priced in September, and spreads have come in by 20 basis points. But with such an amount, there are creeping signs of indigestion – or even a lack of appetite altogether.

Two recent deals that have been scrapped are in uniquely unloved segments of the market. Stelco Holding Inc.'s $300-million attempt was small enough for investors to ignore (liquidity in the secondary market with an issue of that size can be a turn-off). Peabody Energy Corp. scrapped an $800 million sale last week because investors don't find thermal coal to be all that beautiful right now, and the company's willingness to give concessions was perceived as lacking.

Underwriters of Apollo Global Management's buyout of Shutterfly Inc.had to take down nearly $300 million of the $1 billion issue, which included sweeteners to make the deal more palatable to an investment community that's a little gun-shy when LBOs are concerned.

It's worth noting that given the incredibly strong start to the year, investors could lock in gains and head for the sidelines if they so desired. This isn't yet happening en masse, though flows have become less supportive.

Within the CCC ratings space, note how localized the damage is. As the geopolitical risk premium in oil ebbs, the energy sector – and in particular, a few troubled firms (McDermott International Inc., California Resources Corp., EP Energy Corp.) – as well as Frontier Communications Corp. account for more than all the recent damage.

The par value of U.S. corporate CCC debt outstanding is $173 billion, with fewer than 300 issues. That sounds like a lot. But there are nearly 1,900 issues outstanding in the high yield space as a whole, totaling a whopping $1.2 trillion in principal. There's incredible dispersion within CCCs, even within sectors. And a saving grace for the junkiest junk debt may be an effective put, in light of the buildup of cash in distressed funds that have had slim pickings stateside.

Investors shouldn't extrapolate from the trials and tribulations of a few firms in the primary and secondary markets and assume the marginal U.S. corporate borrower will be faced with duress. Nonetheless, it's a situation worth monitoring to see if stress becomes more general than idiosyncratic, and in particular if the primary market starts to dole out more punishment.

Post a Comment