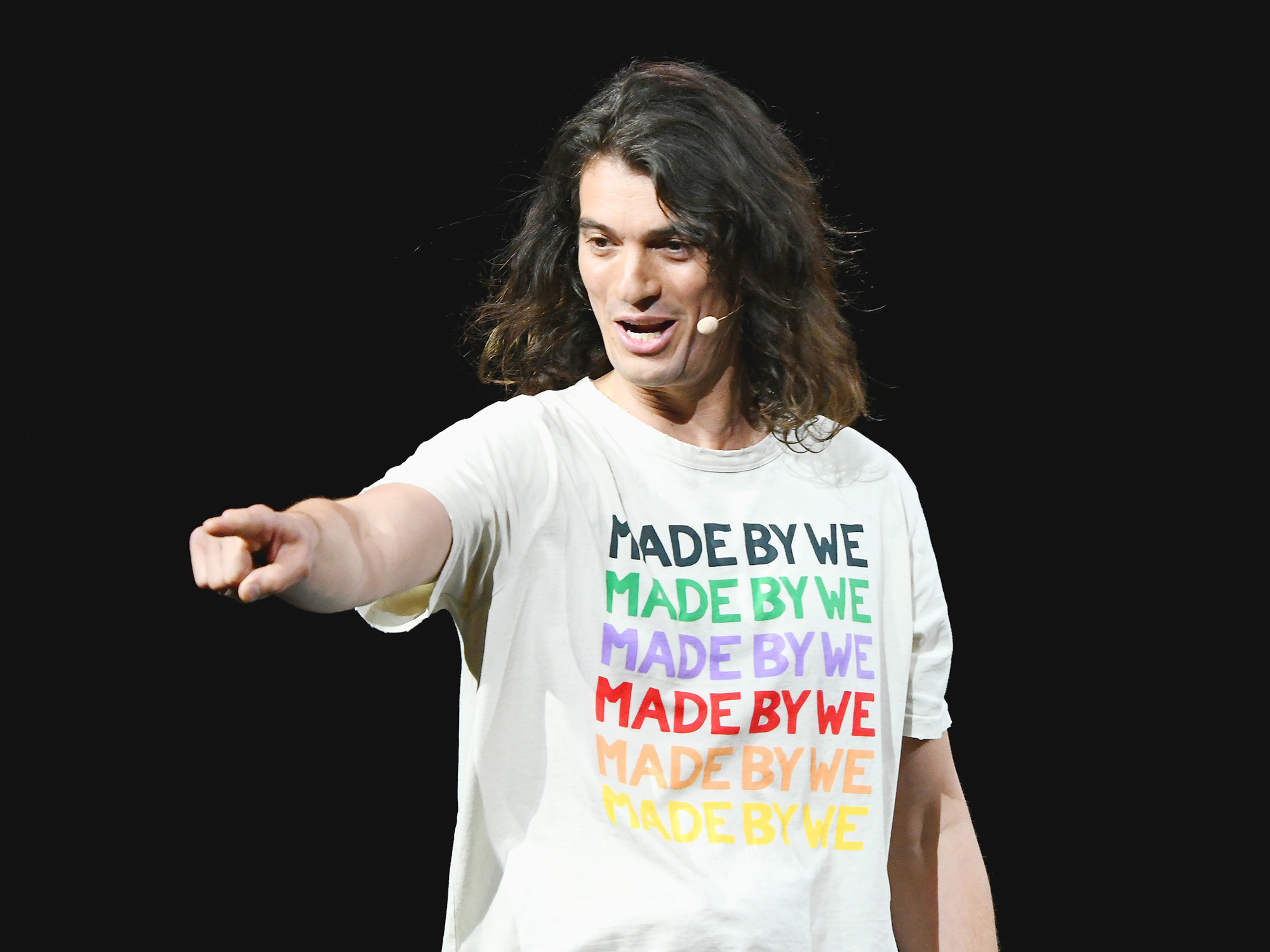

| If liberal capitalism in the West collapses, the postmortem written by historians will surely include, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, tales of Adam Neumann serving up shots of tequila at an office party not long after firing 7% of his staff. The Journal has long chronicled the highs and lows of corporate America: Its portrait of the founder of WeWork this week also featured allegations by unidentified individuals of pot-fueled revelry aboard his private jet shortly before the world's most valuable startup went into a nosedive. Once priced at $47 billion, WeWork, recently renamed We Co., now expects an IPO valuation of only about one-third of that number as potential investors question the company's strategy and Neumann's governance style. The listing is now on hold. Where did capitalism go so wrong? The crumpling of WeWork's sticker price comes at a moment when the entire capitalist enterprise looks to be in danger of keeling over. A system that has delivered unprecedented global prosperity since World War II is now failing large portions of the population: Middle-class Americans no longer automatically expect that their children will do better than them (about a quarter don't.) Many blame the problem on corporations that have maintained a singular focus on maximizing profits at the expense of society and the environment. Indeed, the situation has grown so dire that corporations themselves have started doubting their mission. The Business Roundtable recently declared that the primary purpose of its members should no longer be to deliver returns to shareholders, but to care for "all stakeholders." "It's time for a reset," writes Lionel Barber, editor of the Financial Times, which has turned its pink pages into a crusading voice for capitalist reform. The paper's star columnist, Martin Wolf, lays much of the blame for the West's systemic crisis on a mutant form of "rentier capitalism," with the "rent" being rewards over and above those required to induce the desired supply of goods, services, land or labor, and the rewards accruing to a small group of privileged individuals and businesses.  Certainly, Neumann (above) helped himself freely to the gushers of money that flowed into his business, much of it from SoftBank; he's cashed out of hundreds of millions of dollars in stock, according to the Journal, and borrowed hundreds of millions more against his remaining stake. (The Journal said Neumann declined to comment, citing the company's planned IPO.) But it would be unfair to brand him as the poster-child for all that's wrong with modern capitalism. Neumann reinvented the entire concept of the office, creating indoor space from San Francisco to Shanghai that both predicted and reflected the changing lifestyles and expectations of hip millennials. That kind of visionary entrepreneurialism is the very essence of capitalist endeavor. Indeed, there is a danger that this current bout of hand-wringing about capitalism will produce entirely the wrong results. The Economist, for one, acknowledges the ills of inequality, sluggish productivity growth and environmental decay, but argues that the solutions ultimately lie in the hands of elected governments, not business leaders. To rely on the likes of Jamie Dimon at JPMorgan Chase for fixes "risks entrenching a class of unaccountable CEOs who lack legitimacy," the magazine argues. Besides, it says, the distraction will erode business dynamism. Waiting to take over This is no time for the West to further chip away at the already shaky foundations of its democracy and capitalist systems. On the contrary, both desperately need reinforcing just as an alternative model is waiting to take over: Chinese-style "state-capitalism." It's no coincidence that, as self-doubt grips Western societies, China has abandoned any belief that its own system of top-down economic and political controls is suitable only for itself. That country is now touting the formula as a model for developing countries like Ethiopia and Tanzania. Of course, those who laud state-capitalism often forget to mention its own systemic distortions and wild excesses. A few years ago, Chinese anti-corruption investigators found 200 million yuan ($28 million) in cash at the home of Wei Pengyuan, deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission's coal department, the South China Morning Post reported at the time. The pile of bank notes was so enormous that it took 16 counting machines to add it all up; they ran so hot that four broke down, according to the newspaper. Yet the Chinese system delivers powerful growth, year after year. Its successes "have made China attractive to smaller countries not only as an economic partner but as an ideological standard-bearer," writes the scholar Elizabeth Economy. The lessons of WeWork must be carefully weighed. Neumann's novel approach to office design blurred the lines between work and play—and made him deservedly wealthy. At the same time, he has dissolved other boundaries through self-indulgence; in a particularly egregious case, the Journal reports that he tried to sell the rights to the word "We" to the company from an entity he controlled for $6 million. He also muses about becoming leader of the world, living forever and amassing a fortune of more than $1 trillion, according to the Journal. Ultimately, markets and regulators will decide what parts of Neumann's business and ethics are a work of creative genius, what parts are problematic—and what's plain nuts. This is the way capitalism works. The system urgently needs reforming, not replacing. _______________________________________________________________ Like Turning Points? Subscribe to Bloomberg.com. You'll get our unmatched global news coverage and two premium daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close, and much, much more. See our limited-time introductory offer. The best in-depth reporting from Asia Pacific and beyond , delivered to your inbox every Friday. Sign up here for The Reading List , a new weekly email. Download the Bloomberg app: It's available for iOS and Android. |

Post a Comment