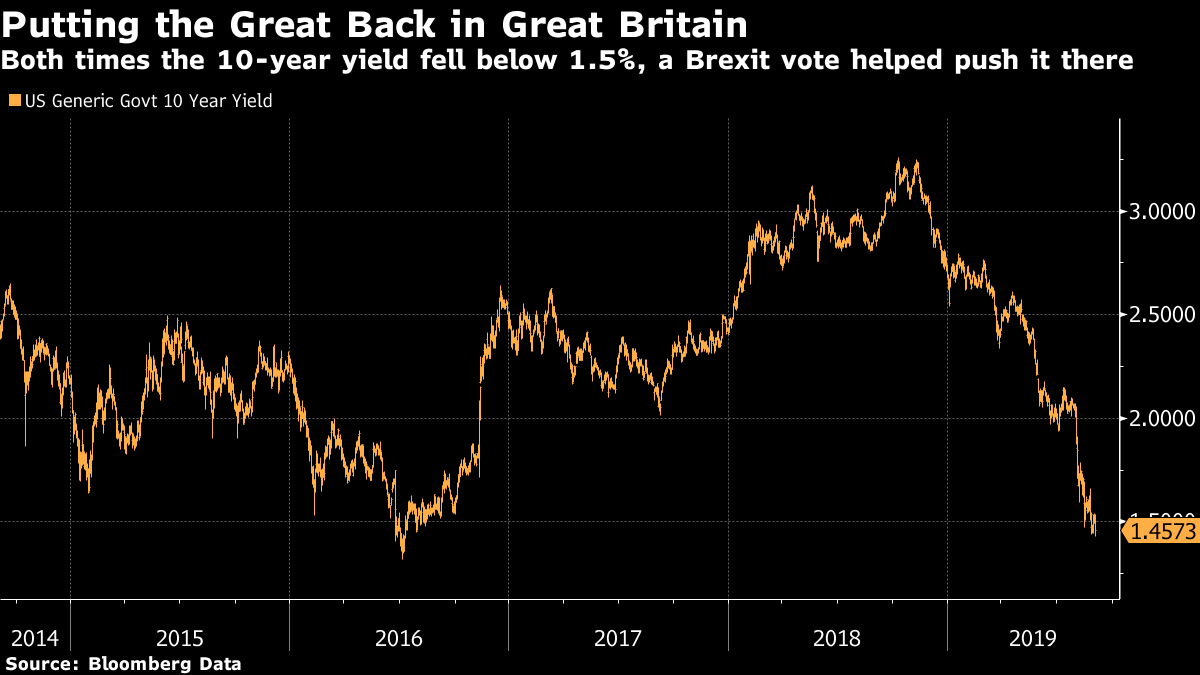

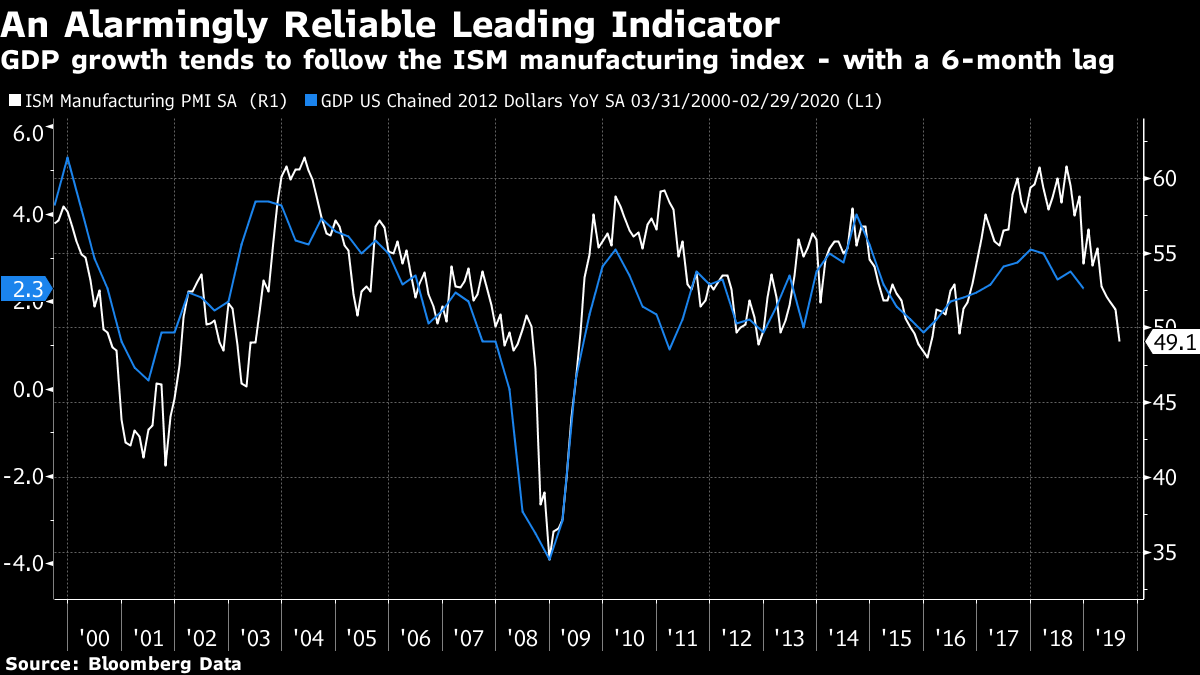

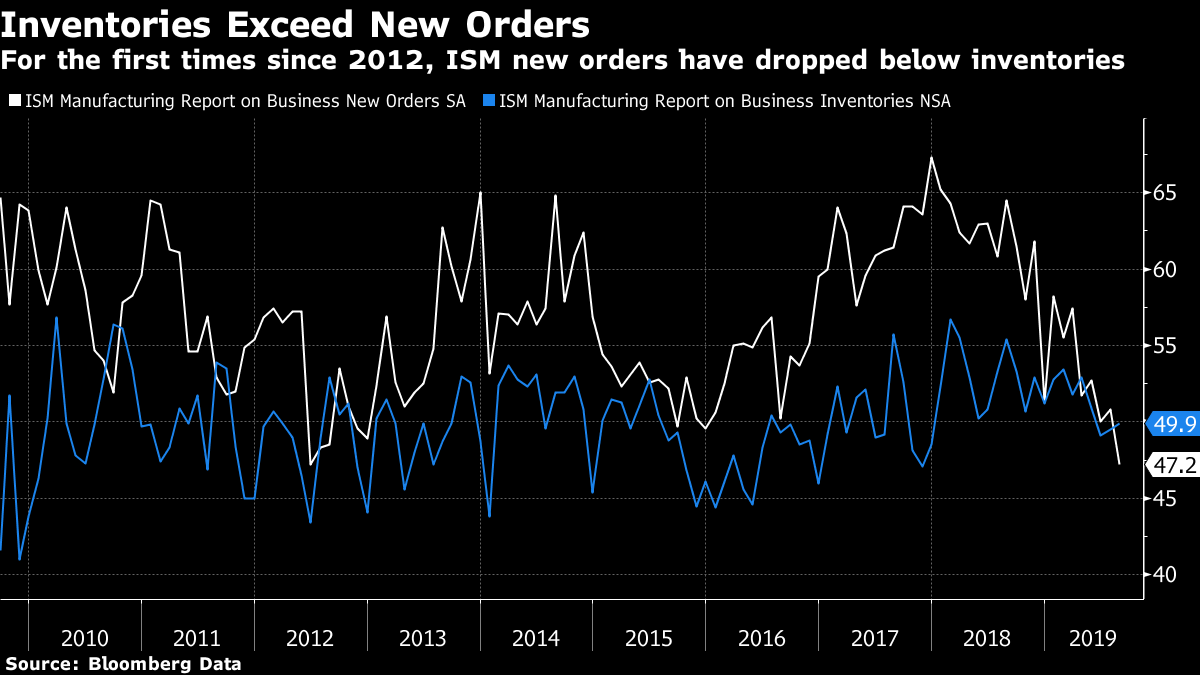

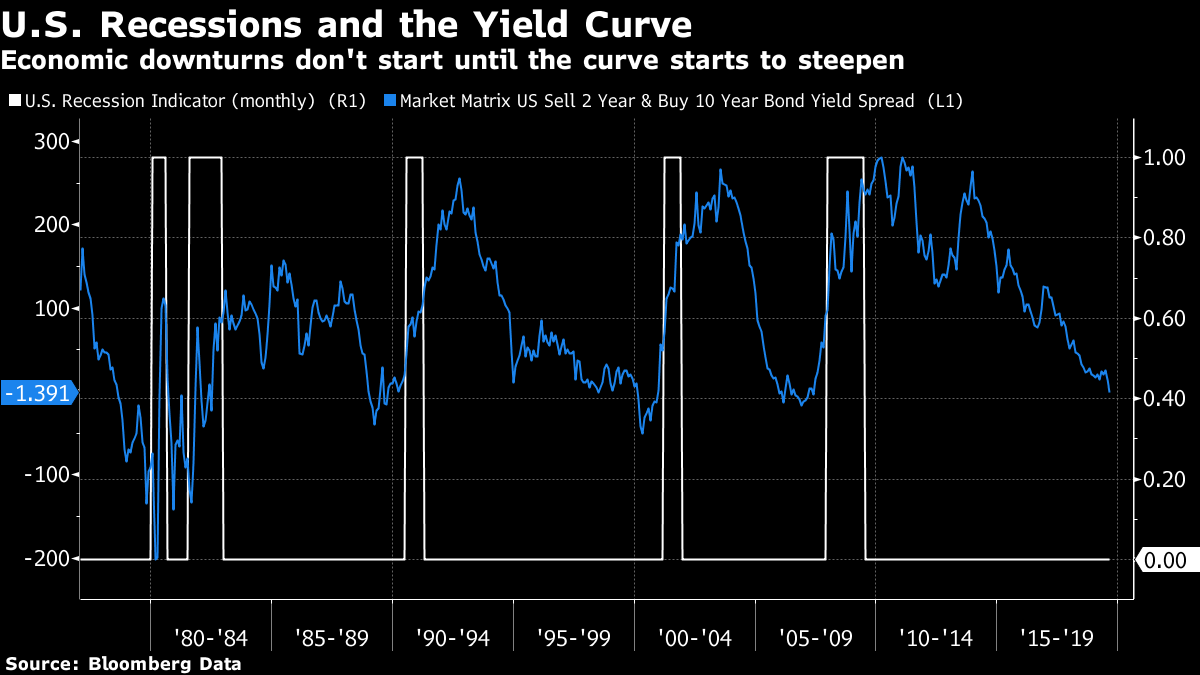

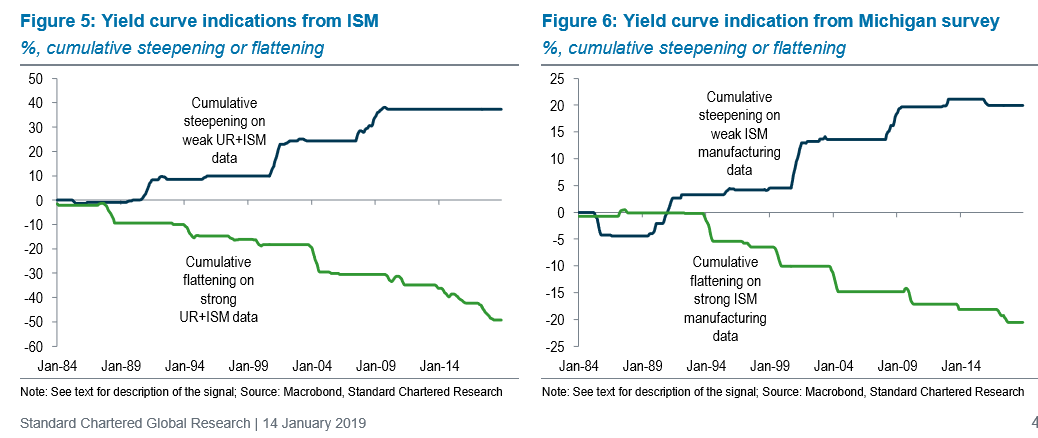

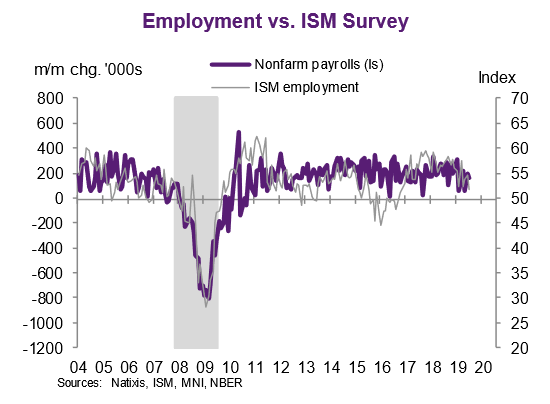

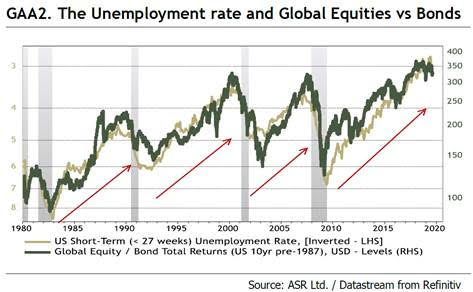

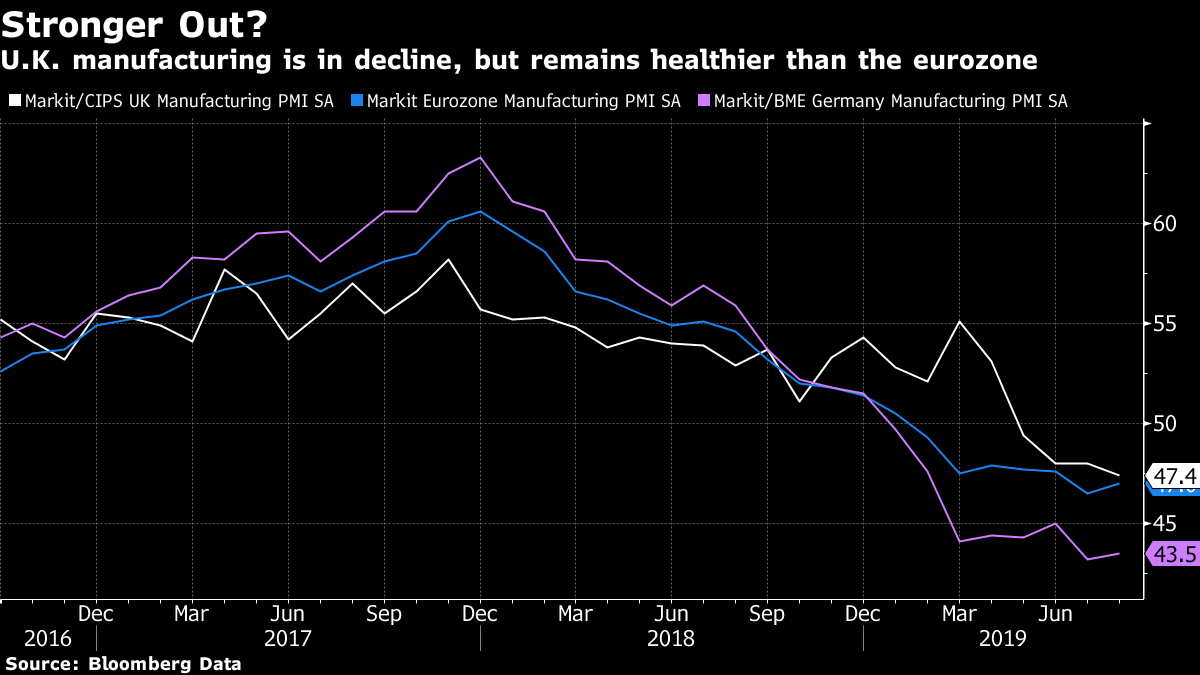

ISM > BoJo. Tuesday was a day of unprecedented drama in the Mother of Parliaments. By the end of the day, new prime minister Boris Johnson had been defeated in his first ever parliamentary vote as premier, and was threatening to call a snap general election. The entire project of Brexit – British exit from the European Union – was on the line once again. Also, Johnson had lost his majority to defections from his Conservative party, and then fired more than 20 of his colleagues from the party altogether. Those he expelled included two former chancellors of the exchequer and the grandson of Winston Churchill. And not for the first time in Britain's interminable, tortuous and torturous Brexit saga, a big moment of drama saw a historic drop in the 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield, the most important building block in global finance, setting the notional risk-free rate for transactions the world over. It hit its lowest level ever during the flight to safety that followed the initial referendum result on June 23, 2016. And it dropped below 1.5% again on Tuesday, to its lowest since 2016, as Britain's political shambles deepened:  It is tempting, particularly for an exasperated British expatriate covering the U.S. bond markets, to suggest that Britain still retains some influence in the world and that the political drama in Westminster has caused record ructions in the bond market on Wall Street. But unfortunately that temptation has to be resisted, because it is not true. What is happening in the bond market is far more important for the world than Britain's Westminster farce. And it has been driven by much more prosaic factors. The Institute for Supply Management said on Tuesday that its manufacturing index for August dropped below 50. That means supply managers are feeling more negative than they at any point in the past three years, and it also implies strongly that there is a risk of a recession. (The index is set so that 50 is the dividing line between expansion and contraction, although in practice a number below about 48 tends to be needed to show a clear recession signal.) As the chart shows, the ISM manufacturing index has over time been a great leading indicator of GDP growth, with about a six-month lag.  If the headline of the ISM report was bad, the details were worse. Much of the business cycle is driven by the interplay between inventories and new orders. When inventories are high and new orders dwindle, there is scarcely any need for new production and economic activity stalls. When inventories have been run down and new orders recover, however, the conditions are there for a restocking boom that ends a recession. Unfortunately inventories now exceed new orders for the first time in seven years:  Faced with such an emphatically bearish set of data, and arguably the most negative U.S. data to appear since the trade conflict began last year, the U.S. Treasury market's yield curve steepened. In other words, the 10-year Treasury yield is once more higher than the two-year yields, as is normally the case. This followed a very brief period of inversion. As has been widely broadcast, an inverted yield curve has been a reliable indicator of an oncoming recession. But it is not a good sign that the curve is steepening again, necessarily, because in the past the curve has invariably steepened following an inversion before the subsequent onset of a recession:  To be clear, the inversion needed to last longer to be a strong recession indicator. Also, the gap between 3-month bill rates and 10-year yields has been a more reliable indicator, and this spread remains inverted. However, if this is the beginning of a steady steepening, it matters. It implies markets are now convinced that rates will come down in the short term, because the economic outlook will give the Federal Reserve no choice. It would be a continuation of the market's attempts (in line with those of President Donald Trump) to bully the Fed into cutting rates. Indeed, research published on Tuesday by Steven Englander, the veteran foreign-exchange strategist now at Standard Chartered, shows that the manufacturing PMI index has been a good indicator of a steepening yield curve in the past. The same is true of the University of Michigan's consumer sentiment survey, which has also weakened recently to its lowest level since 2016. However, consumer sentiment does not yet look anything like as worrying as the manufacturing surveys, and in any case it appears to have less effect on yield curve steepening, as these charts show:  In the short-term, the greatest impact will be to amp up the importance of the U.S. non-farm payroll data for August due out on Friday. The market moves may not be sustained if the ISM number proves to be a rogue data point, while we could see the trends emphatically extended if the employment number is indeed weak. And to be clear, ISM has over time been a fantastic leading indicator of employment. The following chart, produced by Joseph LaVorgna, the chief U.S. economist for Natixis, makes that clear:  There are wider market ramifications. For much of the last decade, we have grown accustomed to a stock market whose valuations have been propped up by low bond yields. But the ISM data was treated as an example of bad news meaning bad news. Lower bond yields did not stop the stock market dropping. And this makes eminent sense. The following chart from Absolute Strategy Research demonstrated beautifully that the relative performance of stocks compared to bonds (shown in the thick dark green line) is very closely tied to the U.S. unemployment rate (shown on an inverted scale in the thinner gold line). Stocks outperform bonds whenever the unemployment rate is falling, which is most of the time. During those brief periods when unemployment rises, bonds beat stocks:  It is hard to be enthusiastic about bonds when their yields are already very low in the U.S., and outright negative in much of the rest of the developed world. But if the data over the next few weeks and months turns out to support the worrying message of the ISM manufacturing index, life could be very hard indeed for equity investors. Analyze this, Brexit edition. What do investors need to know about the latest episode in the shambles that is Brexit? The bottom line is that it is an ungodly mess, but for non-Britons who must by now be watching an ancient democracy's nervous breakdown with amazement, I hope the following points are helpful. I'm writing at length but I hope this is useful. Boris and the Brexiteers have seriously overplayed their hand: The strategy was to push forward ruthlessly, and dare a disorganized opposition to try to get in their way. But the move to suspend parliament was (rightly) seen as an overreach. The same is true of Johnson's decision to fire every cabinet minister who did not back him in the leadership election, and of the recent summary dismissal of government advisers suspected of leaking.When this provoked a coordinated response to take control of parliament and block Johnson from accepting a "no-deal" exit, that strategy could be seen not to be working, but it provoked another overreach. The threat to expel any rebel from the party was seen as an outrage, coming in a year when dozens of Conservatives had rebelled against former Prime Minister Theresa May and kept their jobs. As a result a number of very senior politicians, many of them now beyond ambition, felt inspired to push through with the rebellion. When it came to the debate, Johnson's normal eccentric "schtick"came over as unconvincing and lacking in seriousness, while the behavior of Jacob Rees-Mogg, appointed by Johnson as his leader of the House of Commons (responsible for guiding government business) was inexplicably arrogant. The image of Rees-Mogg lying across three seats with his eyes shut while leading one of the most important parliamentary debates his country had seen in years enraged many on his own side. It is likely to live on as a meme of arrogance and entitlement for years to come. Johnson's ruthless strategy can therefore be declared dead. Brexit may survive this, but it will need a different approach. Only a few days ago, he had convinced many that his strategy would carry all and deliver a no-deal Brexit. It will not now be that easy, and the chances of no-deal have now reduced. This explains why sterling rose for the day despite unprecedented parliamentary chaos. An election next month is still not a given. The U.K. made a huge constitutional change under the coalition government of David Cameron's Conservatives with the Liberal Democrats, which was in power from 2010 to 2015. Originally aiming for a sweeping new constitutional settlement, little was done except for a new law mandating fixed-term elections. Until then, a general election could be held no later than five years after the previous one, but the prime minister in power was at liberty to call an election earlier than that. If a simple majority of MPs agreed, the election would happen. Now, the law requires a prime minister to serve for five years exactly. An early election can only happen with the agreement of two-thirds of MPs. That significantly strengthens parliament against the executive. The upshot for now is that Johnson can threaten a snap election and effectively bill it as a second referendum on Brexit, but it is not clear that other parties will go along with him. Initially, opposition leaders are saying they would only agree to an election if their legislation barring a "no-deal" exit is passed first. (That could still be repealed after an election, but only if the voters elected a majority of MPs favoring "no-deal.") Without that, it is conceivable that Johnson has no choice but to limp on without a majority and without authority until the opposition decides to put him out of his misery. Such an outcome would be dreadful for any chance of coherent economic policy for the U.K. But it would probably allow some recovery for U.K assets, which are priced on the assumption that no-deal is a significant risk. Without a majority, however, an election long before the current due date of 2022 is more or less certain. Jeremy Corbyn becomes the pivotal figure. Labour Party leader Corbyn is (fairly) regarded as an ideological left-winger. He has in the past been strongly anti-EU, and this has handicapped his party's stance. But he retains control of his party in the country, and now becomes a critical figure. He is also, bizarrely, receiving praise and strategic advice from Blair, an extremely different Labour politician. Knowing that many of their voters voted for Brexit, Labour under Corbyn has done a terrible job of formulating a position. But many of Corbyn's most enthusiastic left-wing supporters are also passionately anti-Brexit. If Labour decides to go into an election offering voters the chance to reverse the referendum result and stay in the EU, then the chance of anti-Brexit MPs forming a majority in parliament becomes quite strong. This would arguably have the same legitimacy a second referendum to overturn the first. If Labour stays equivocal, then the parties opposing Brexit remain very divided. An election might easily be decided on issues other than Brexit. Should Corbyn decide to throw in his lot with those opposing Brexit, then the chances of staying in the EU rise considerably. The problem for investors is that the chances of a Corbyn premiership also rise considerably. U.K economic numbers are already subsiding, towards the kind of levels seen in the EU. As Corbyn would be governing a country where about half of the population was infuriated by the establishment's failure to follow instructions and leave the EU, the U.K. would still not be an attractive investment in these circumstances.  A second referendum is, just about, possible. In indicative votes earlier this year, a majority of MPs voted against holding a second referendum. The risk that a second referendum would merely divide the country even more starkly is very real. There is no evidence that a second referendum would be decided by any wider a margin than the first (52-48). If the polls are right (and they were wrong in 2016), another referendum would deliver roughly the same majority for remaining that the first one delivered for leaving. That would stop Brexit but would be a disaster for the country's long-term governability, as some 48% of the population would have voted twice to leave, and been denied. Blair's advice was interesting: "Should the Government seek an election, it should be refused in favour of a referendum. It is counter-intuitive for opposition parties to refuse an election. But in this exceptional case, it is vital they do so as a matter of principle, until Brexit is resolved."Brexit is an issue which stands on its own, was originally decided on its own and should be reconsidered on its own… [Corbyn] should see an election for the elephant trap it is. If the Government tries to force an election, Labour should vote against it." It is just about conceivable that this could happen. But unlikely. Under the U.K. electoral system, anything is possible. Like the U.S., Britain has a "first past the post" electoral system. Whoever gets the most votes in a constituency gets to be the M.P., even if they are well short of 50% of the vote. That injects the current position with radical uncertainty. Somebody could win a majority with far short of 50% of the national vote. There are significant nationalist (and very pro-European) parties in Scotland and Wales, who will probably make gains. Both the Liberal Democrats and the Greens (who have only 1 MP) have meaningful bases of support, and they strongly favor remaining in the EU. They might easily win plenty of four-way or five-way races. The Brexit Party, under the talented populist politician Nigel Farage, won the most votes in the elections to the European Parliament earlier this year. Brexit-supporters might coalesce around Johnson, or many might find Farage more appealing, particularly after the dreadful Johnsonian mess of the last few days. Or the two pro-Brexit parties could cancel each other out. Then there are many MPs who have resigned from both the major parties over their Brexit stance. They would have the benefit of incumbency and add further uncertainty. Some of the Conservatives who have just been fired by Johnson might well have a chance of winning as independents. Put all of this together and nobody can say they know how an election would turn out. Polls before the events of the last few days had shown Johnson in first place and gaining, but short of the numbers likely needed for an overall majority. A pro-Brexit coalition led by someone other than Johnson, or a pro-EU coalition led by someone other than Corbyn are both perfectly conceivable. So is Prime Minister Johnson, this time with a mandate. And so is Prime Minister Corbyn.  So. The upshot is that British politics is a total mess. The possibility of a no-deal Brexit has just reduced sharply; but the level of uncertainty is much higher. This is a recipe for U.K. assets to recover a little from their deeply discounted levels, and then stay volatile as the drama continues. Negative yields are gold-positive. One final note: gold is on the rise again. I have suggested before that this is an outcrop of the negative-yielding debt phenomenon. Gold's great disadvantage is that it yields nothing. But when bonds, another sensible conservative investment for the risk-averse, are offering an outright negative yield, then zero begins to get competitive. And indeed, gold's ups and downs as it rises out of its bear market of last few years have been almost perfectly in time with the total quantity of negative-yielding debt. The following chart is adapted from one published by Jim Bianco of Bianco Research:  Gold has already risen a lot so some opportunity has been lost. But if the current gloomy economic outlook proves to be justified, the case for some gold in the portfolio continues to strengthen. |

Post a Comment