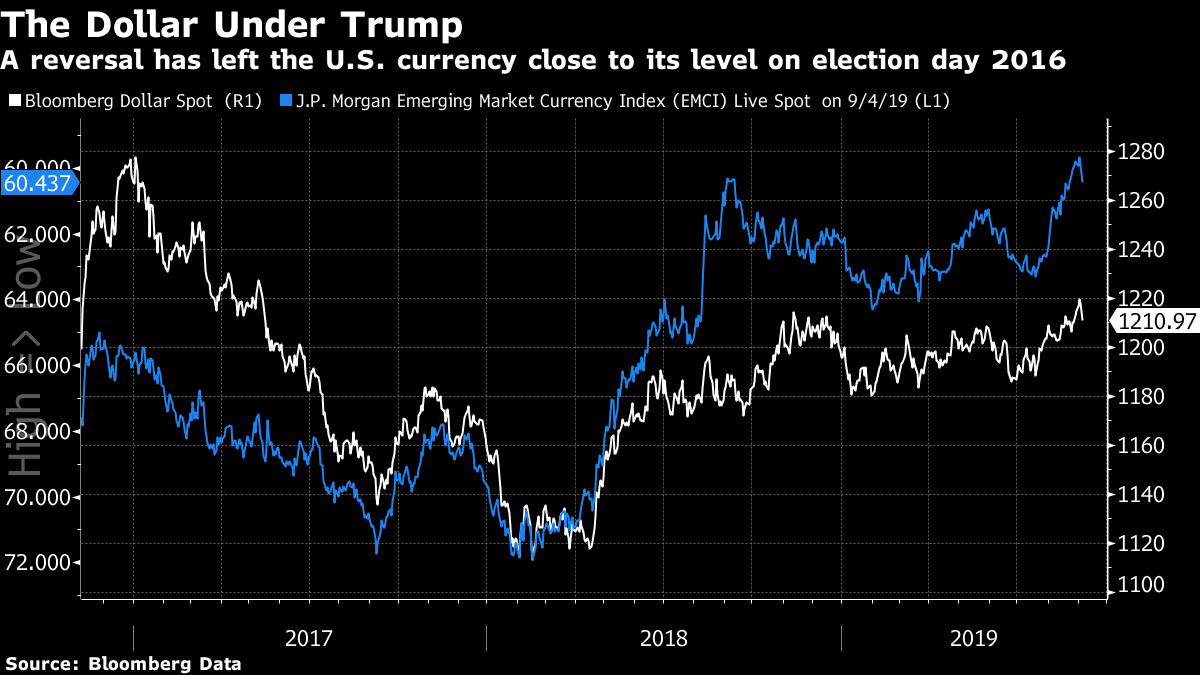

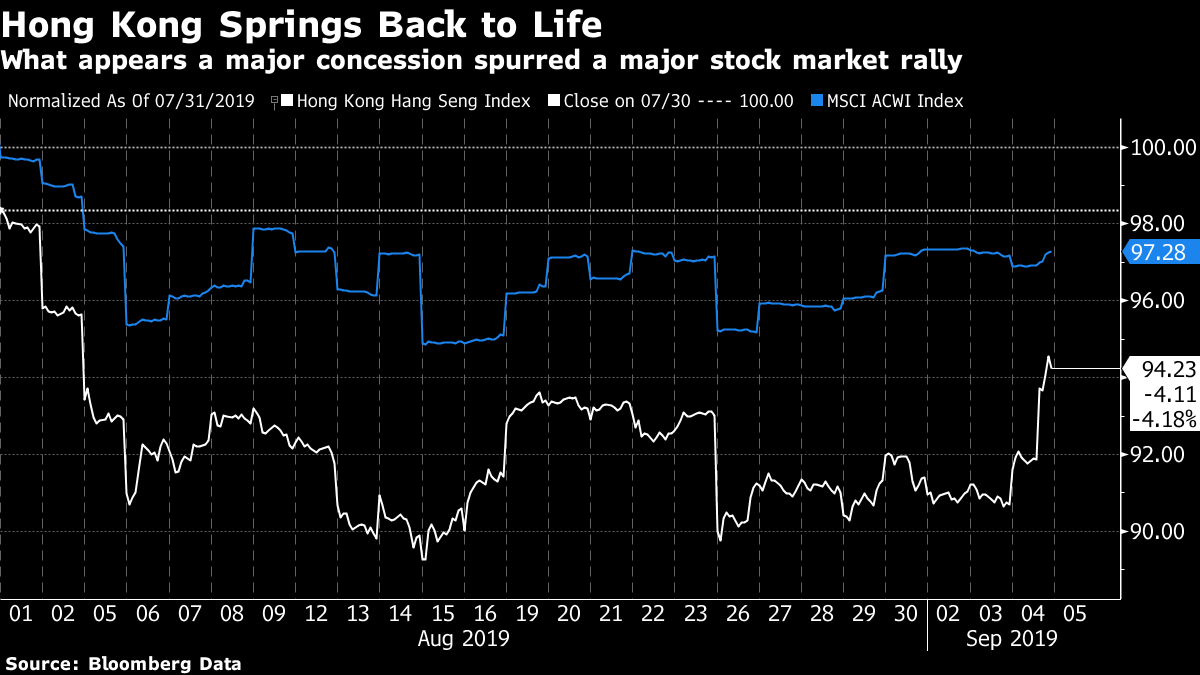

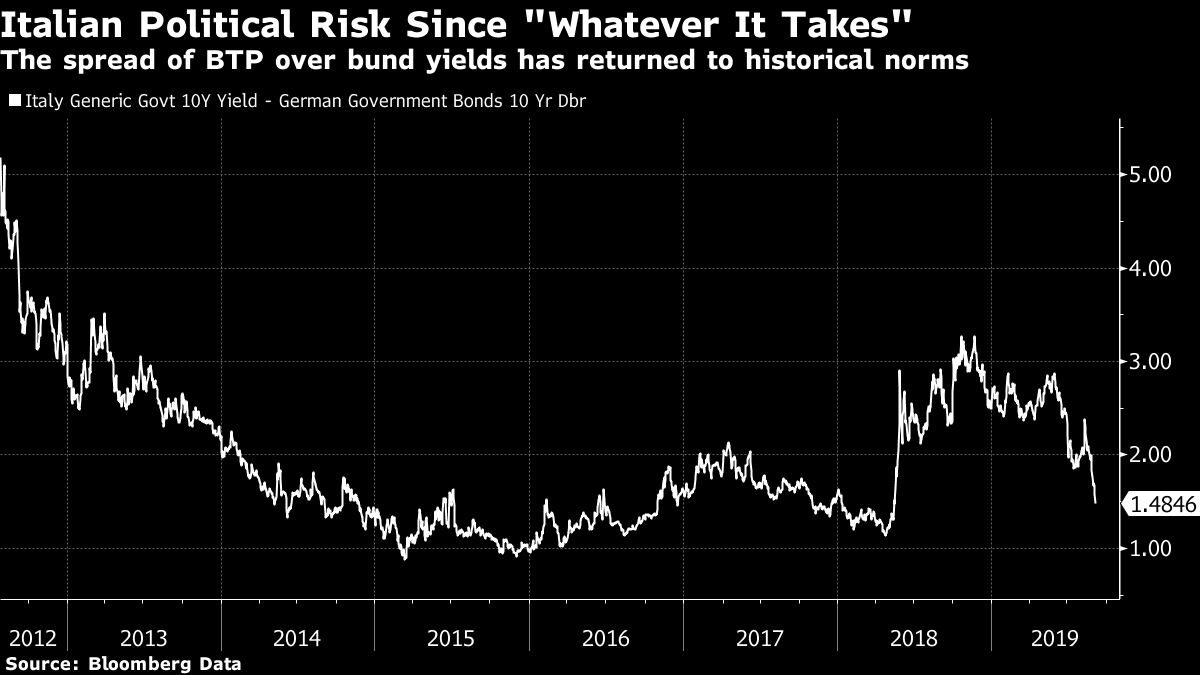

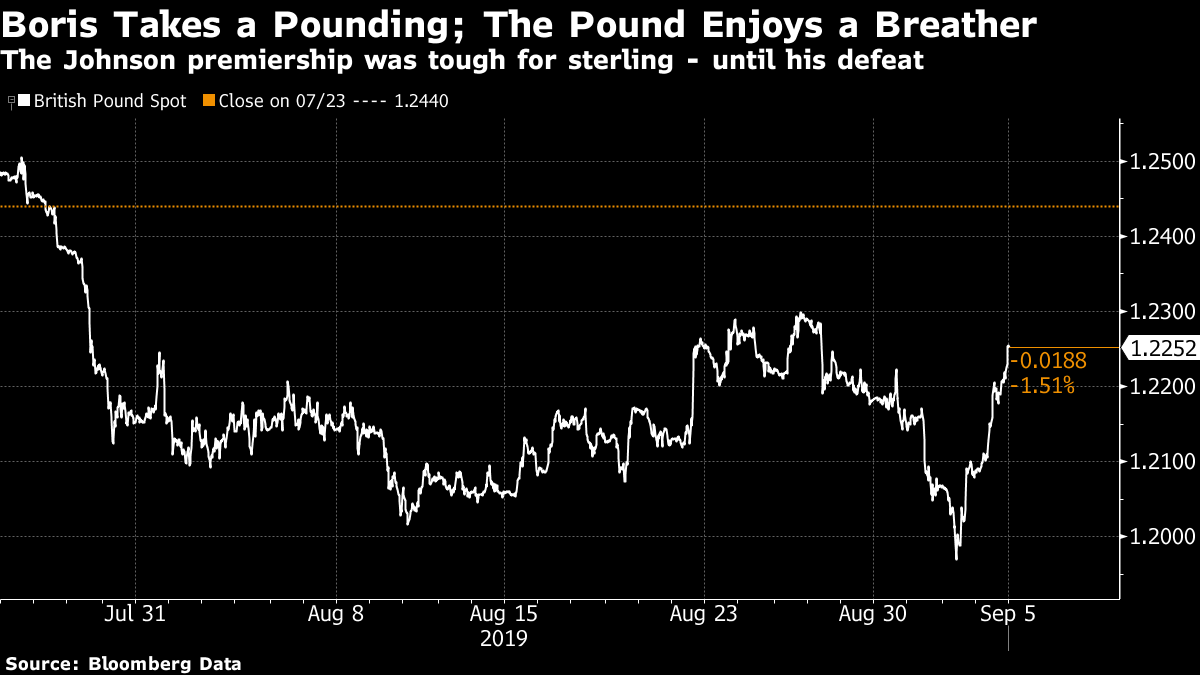

Catastrophe averted, perhaps.If there is anything markets are bad at, it is pricing in low-probability extreme events. We learned that in spades during the credit crisis, and global markets are treating us to another demonstration now. The dollar has been strong recently – and plainly too strong for the taste of the president. But it had a sharp downward turn Wednesday. In the chart below, the white line is Bloomberg's broad dollar index, and the blue line is JPMorgan's emerging market currency index, against which the dollar has been particularly strong:  Why such sudden dollar strength? Not because of anything much that has happened to the U.S. economy. We still have a raft of data, and a lot of Fedspeak, to look forward to before the week is out. And it also had little to do with the bond market, recently at extremes, which enjoyed an unusually quiet day. There is no particularly great reason to think that the long-term perspective is healthy. However, in three different points of the globe, a small but growing risk of disaster has significantly reduced. First, in Hong Kong, the city's chief executive has withdrawn the extradition bill that triggered months of protests. This is widely seen as a significant concession that implies the Chinese authorities do not have the appetite for a confrontation at this point. This in no way resolves the problematic status of Hong Kong or the issues that have been uncovered over the last few weeks. But the nightmarish visions of a repeat of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre that had troubled global investors have receded. Nobody can put a good number on how great that probability was before, or how great it is now, but the way the Hang Seng Index rallied on Wednesday shows that a far lower probability of disaster is now being discounted. After seriously lagging the main world stock markets during the disturbances, Hong Kong stocks enjoyed an emphatic recovery:  Then there was further good news from Italy, where an unlikely coalition of the center-left Democratic Party and the populist-left Five Star Movement continues to take shape. This follows more than a year of elevated perceived risk as Five Star made an implausible alliance with the anti-immigration League. A few weeks ago, it seemed that the League was breaking up the coalition and about to seize power. Now, the League appears to have exiled itself, while a much more market-friendly party has entered government. The chances of a head-on confrontation with the EU over fiscal policy have dropped dramatically. Italy still has a dreadfully sluggish economy, and few tools with which to stimulate it. The only reason the new coalition does not look totally unwieldy is because it is at least a little more coherent than the one it replaces. But with the chance of catastrophe much reduced, the spread of Italian government bond yields over equivalent German bunds has dropped below 1.5 percentage points. It is now at levels typically seen in 2017, before the last election. Once the spread seemed alarmingly to be heading to the extremes reached during the eurozone's sovereign debt crisis, before the European Central Bank's Italian governor famously promised to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. Now, Italy is much less of a source of anxiety for those trying to put a price on catastrophe risks:  Finally, there is the U.K. The country is in a deep political mess, with no obvious resolution. But the events of the last 48 hours have caused a sharp swing in the perceived probability of the country leaving the EU without a deal – a scenario that investors believe is the single worst outcome to the country's Brexit debacle. The chart shows the pound's exchange rate against the dollar since Boris Johnson, who appears happy to countenance a no-deal exit, took over as prime minister. His premiership has been seen as deeply alarming; and his historic defeat is seen as greatly reassuring:  Political uncertainty is extreme and while Johnson has sustained a defeat he may yet have the last laugh. But the chances of a disaster scenario have plainly just decreased, and so the pound has strengthened. More on Brexit below. When investors are worried about risk, they tend to shelter in the dollar. And so, with catastrophe risks reduced in Hong Kong, Rome and London, money flowed out of the dollar, and made life a little easier for the U.S. president and his central bank. Judging low-probability extreme risks is, as I said, notoriously difficult. There is every reason to fear that the market has gone too far in response to some market-friendly news. But everyone is grateful for something to celebrate. The World Awaits BoJo's Plan DLet us return to Brexit and the interminable struggles of Britain's political class. What are the realistic outcomes? In the longer term, as I argue elsewhere, it will get ever harder to escape a drastic constitutional overhaul of the kind that the U.K. has avoided for centuries. But we have to survive the short term first.Boris Johnson has been drastically weakened, though as prime minister he still holds more power than anyone else. Meanwhile, much depends on the next move of an incoherent opposition group that has failed to come up with a common strategy and may well continue to do so. For BoJo, Plan A was to prorogue parliament, cutting off time to come up with any alternative to a no-deal Brexit; Plan B was to cow any rebels into submission by threatening to expel them from the Conservative Party; and Plan C was to call a general election if all else failed, and dare the opposition to go to the country. Plans A and B have failed. Parliament has denied him the election he wanted, but he may yet be able to win on the issue by convincing the electorate that his opponents are too scared to go to the polls. What could Plan D be? One candidate appears to be to use the House of Lords (unelected) to filibuster out the bill that would stop him from executing a no-deal Brexit. The Lords are looking at about 100 separate amendments, and they may yet have the ability to delay the legislation into submission. Other than that, he is giving few hints – although perhaps the most bizarre suggestion is that he could call a motion of no-confidence in himself and force a general election that way. All these options would do considerably more damage to Britain's unwritten constitution than the EU ever did. But what can the opposition do? Assuming they can pass their anti-no-deal legislation, they probably want to move on then to a general election. They can call a vote of no-confidence, so to an extent they can force the issue. It appears – but nobody is quite sure as we are in untested constitutional waters – that they could simply leave the prime minister in office while blocking his every attempt to do something. In practice, that situation is untenable. They may be able to make Johnson look ridiculous by leaving him hanging for a while, but they cannot do this for long. And they have to avoid any impression of being scared of an election. The odds then are strong that there will be a U.K. election within a matter of months. The government that results could be almost anything. The British electoral system allows for strange victors to emerge when there are numerous viable candidates. The chances of a stable government with a clear mandate on how to handle Brexit remain slim. Meanwhile, if no-deal is to be avoided, and politicians are not going to seek a mandate for giving up on Brexit altogether, then a deal will have to be made somehow. Nobody likes talking about it, but that will require negotiations with Ireland over the border, and may well involve forcing an outcome on Northern Ireland's Unionists that they dislike – something that is much more plausible now that they are no longer able to keep the government in power. That is to say that any outcome will be prohibitively difficult to achieve. And this uncertainty will play out as the British economy is palpably weakening. Outright disaster seems less likely than 48 hours ago; persistent chaos as the country and the economy drift looks ever likelier. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment