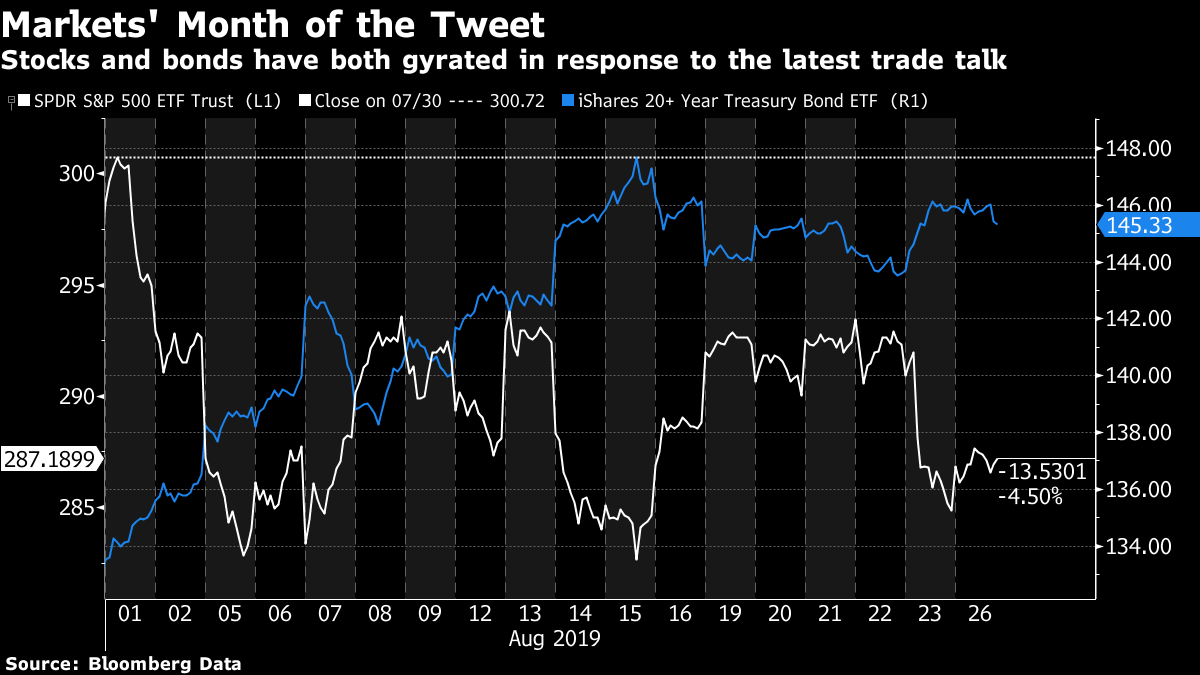

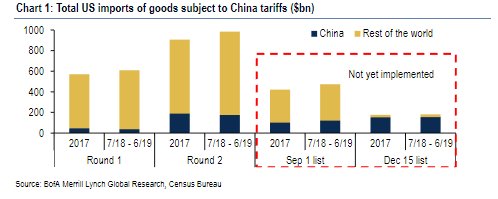

@RealDifficultTime to follow markets. Like many others who earn their living prognosticating markets, I try my hardest to keep from handicapping political developments and their influence on markets. But it's no longer possible to avoid politics when commenting on markets. Blame Donald Trump's Twitter feed. Ahead of the 2016 election, markets moved on the assumption that a Trump presidency would be negative for markets. His stances on immigration and protectionism more or less assured this, along with his unique personality. Many feared Trump was unfit for the job. But the "Trump is market-negative" narrative survived only a few hours after the election result became clear. It was replaced with a "Trump means growth" narrative thanks, in part, to choice of advisers, who included a few key alumni of Goldman Sachs. The first year of the Trump administration was devoted to deregulation and corporate tax cuts, which equity markets loved. The thinking was that infrastructure spending might come next. Protectionism was scarcely mentioned. And 2017 proved to be one of the greatest years for global stock markets on record, with the MSCI All-Country World Index soaring 21.6% with minimal volatility. Early in the Trump administration, investors appeared to have tuned out his inflammatory tweets. After a few initial incidents, such as the run on Boeing shares when the then president-elect complained about the cost of the next Air Force One, a pattern was soon established that negative attacks on companies had little to no impact on their share prices, while positive tweets only provided a temporary boost to companies' stock. All the while, political noise and polarization grew uglier as markets soared higher without interruption. That era is over now. Trump's Aug. 1 tweet announcing a new wave of tariffs on Chinese goods to start at the beginning of September prompted a sharp drop in stocks and a rally in government bonds. Ever since, stocks and bonds have moved tightly in relation to each other, veering up and down in response to the latest political news, and particularly the latest Trump tweet:  This adds an element of randomness to everything in markets. Fundamentals no longer matter. To predict the next shift in sentiment between risk-on and risk-off, you need to know what Trump is going to tweet and when. If you don't have an eye over Trump's shoulder as he taps on his mobile device, your best strategy is to wait for his tweet to appear and react as swiftly as possible. In general, as the chart shows, if the market has recently been up, you should expect it to go down, and vice versa. Why are we so much more bothered by @realDonaldTrump now? The following list is not exhaustive, and the different effects are not mutually exclusive. But I would suggest: Trump is livestreaming his own meltdown. This point comes up often. The presidential Twitter feed has long provided an insight into Trump's personality, and most have disliked what they have seen. But for the most part, it has been possible until recently to dismiss the missives. Trump's tweets reveal the president to be self-obsessed and vain, the argument went, but so what? Other politicians have similar flaws; the only difference is that they try to hide them. It's hard to dismiss the tweets of the last few days this way. The average professional investor is not equipped to be a psychiatrist, which makes the problem harder. But to the layman, Trump appears to have moved from pettiness and vanity to something more serious. Retweeting with approving comments someone who likened him to the "King of Israel" and subsequently joking about being the "chosen one" seems unhinged to many in markets. You can throw in his "ordering" U.S. companies to boycott China, and speculating about whether Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is the greatest "enemy" of the U.S. If Trump really is broadcasting evidence that he's not fit to do his job, this gives market participants reason to watch his tweets and react accordingly. Whatever our politics, any fresh evidence than the president of the U.S. is not fit for the office is reason to be very negative about the outlook for the U.S. and the world. The trade war: This time it's serious. The next chart from Bank of America Merrill Lynch illustrates the problems nicely. For the first rounds of products on which Trump announced tariffs, Chinese exports made up only a small proportion of U.S. imports. The latest round of tariffs, however, has reached the point where things get serious.  The tariffs originally due to start next week and subsequently postponed to Dec. 15 covered goods imported almost exclusively from China (and also very popular with consumers). They may well hurt the U.S. more than China. Market strategists knew this, and assumed Trump would not go beyond his second round of tariffs. The guiding theory was that Trump was making a point and posturing, without trying to demand any great sacrifice from his populace. His Aug. 1 tweet declared that theory to be wrong and forced markets, now devoid of their prior certainty, to pay close attention to his Twitter account. The trade war: It's now about more than trade. As George Magnus, a former UBS AG economist who is now at Oxford University, put it: "Isn't the answer to 'What's wrong with the global economy' that the global system, aka Bretton Woods II, is coming apart at the seams?" Trumpism was always hostile to the internationalism that moved from the Marshall Plan to the creation of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to the modern array of global and regional institutions, from NATO through the European Union to the World Trade Organization. There has been reason to question how much change Trump can render to those institutions beyond a certain personal rudeness. That view now looks complacent. This is partly because hostility to Bretton Woods II is about a lot more than Trump. Two decades ago, hostility to the WTO came from the left and was driven by anger that the developing world was being exploited. Now it tends to come from the right, and by anger that the developed world is being exploited. Either way, it is under intense attack. Once Trump's Aug. 1 tweet made clear that trade confrontation was for real, investors grew far more sensitive to developments such as the unrest in Hong Kong or the fresh divisions between India and Pakistan over Kashmir (both of which might have developed differently with a more typical U.S. foreign policy). The situation with Denmark also supports the notion that erratic presidential behavior can do real damage to global institutions. For those not following, Trump canceled a state visit to the country because he thought the prime minister's refusal to countenance selling Greenland to the U.S. had been made rudely. As Denmark is a NATO member which, unlike many other European countries, sent troops into combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, this was seen as a startling development. Of course, the Trump administration took a clear anti-internationalist position from the first, leaving the Paris climate accords and the agreement to limit Iran's nuclear ambitions. But with each extra step the administration further damages Bretton Woods II and brings it closer to irreparable damage. And so Trump tweets have greater impact. Faith in institutions is now in question. The U.S. constitutional system is famously built on checks and balances. Those checks can be assumed to keep a president with an erratic personality from doing too much harm. Tariffs are different, because they don't have to go through the sausage-making machine of Congress and the courts to take effect. This raises concerns about the strength of institutional safeguards more generally. What's more, congressional Republicans' willingness to act check on the executive seems to have disappeared. The Republican Party has a business-dominated wing that's totally out of sync with the president on both protectionism and immigration, but somehow this hasn't affected the party's behavior in Congress. Without an aggressive check from Congress, there's far greater reason to worry about presidential pronouncements. In particular, the Fed is now in question. For markets, the Fed matters a lot. Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan are seen as far more consequential to the history of securities markets than the presidents who appointed them. And Trump had been reassuringly orthodox in his treatment of the Fed in his first two years in office, having made a point by replacing the Obama-appointed chair Janet Yellen with Powell, a Fed governor for several years. Other nominations for the Fed board similarly signaled continuity. There are plenty of academics who favor drastic root-and-branch changes for the Fed who could have been nominated but weren't. The last year has seen a change. Trump's attacks on the Powell are seen as irresponsible, while recent Fed nominations have seen the White House attempt to put candidates who would alarm the market onto the central bank's board. Republicans in Congress have proved to be a barrier on this issue. And Powell's term does not end until after Trump's first term is up. But the sight of the president of the U.S. calling his own appointment to the Fed chairmanship an "enemy" is alarming. Underlying the alarm at the Trump tweets is an implicit assumption, which is that U.S. institutional stability can no longer be taken for granted.

Trump seems prepared to let the stock market fall now.

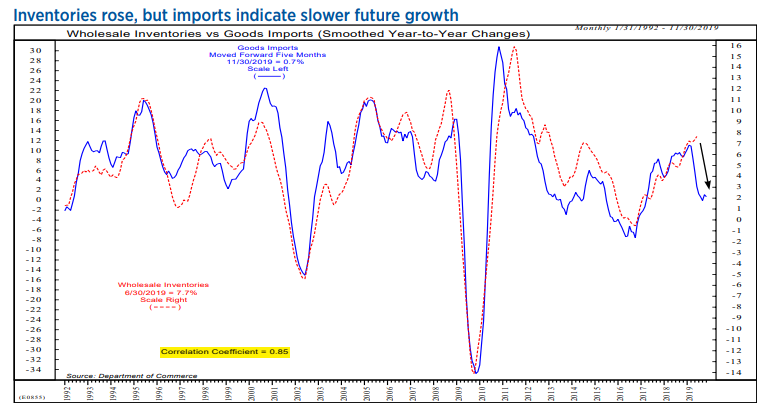

One other great safeguard, for those who cared about the price of stocks, has been that Trump judges himself by the stock market and doesn't want it to fall. He tends to avoid actions that will cause it to fall even though the stock market matters very little to his electoral base. In the last month, though, he has shown some willingness to let stocks slide. As he commented last week: "My life would be much easier if I just said, 'Let China continue to rip off the United States.' All right? It'd be much easier, but I can't do that." That attitude suggests a new readiness to take a more "difficult" path, and for Trump that would involve lower share prices. For all of these reasons, I am powerless but to suggest that anyone who wants to follow markets in the short term also needs to follow @realDonaldTrump on Twitter. Whenever the market is up, be prepared to sell, and vice versa. The alternative is to look to the long term and try to find investments which are immune to political developments, but that's not much easier. Few reliable indicators are unambiguously pointing to a U.S. recession, but a number are moving in a disconcerting direction. For the latest version, take a look at this chart produced by Ned Davis of Ned Davis Research:  This shows inventories with a six month lag, compared to import orders. They track each other closely, and this is in accord with intuition. If a company orders a lot of imports in January, that will tend to raise its inventory by July, and vice versa. The chart currently shows inventories at their highest in several years, following a sharp increase in import orders that has now ended and gone into reverse. This isn't difficult to explain. Companies anxious about future tariffs brought forward their purchases. That led to a buildup of inventory which we can now expect to gradually come down over the next few months. This explains why the first year or so of the trade conflict has had relatively little corporate or economic impact so far, while giving reason to fear that that might change before much longer. And if that sounds bleak, also note that this measure doesn't yet offer as much reason for concern as it did in the months following the surprise Chinese devaluation in the summer of 2015. On that occasion, a recession was averted, even with the Brexit referendum arriving to ratchet up global uncertainty still further. Back then, a new splurge of credit from China was chiefly responsible for the uptick. To avert a recession in the U.S. again this time, it will help if they can perform the same trick again. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return?Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment