Adjustment in mid-cycle. Maybe Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell should run for U.S. president. The spectacle on Wednesday of his press conference after the central bank announced the first cut in its target overnight interest rate in a decade, was painfully reminiscent of the Democrats' 10-person debate the previous day. That line-up of suspects came with well-rehearsed lines, while looking wary of their interrogators and desperately trying to avoid a misstep. All of them might find the experience good preparation if they ever find themselves running the Fed – and Powell did a better job than usual of getting his soundbite off his chest. That soundbite, to be clear, was his description of the rate cut as a "mid-cycle adjustment." He went on to make clear that it was different from a steady campaign of rate reductions, and that the cut had an element of "insurance." The stock market loathed this description and dived dramatically as the press conference continued only to perk up after a questioner pointed out that stocks were down and Powell quickly made clear that he was not ruling out further cuts. But the bottom line must be that Powell and the broader Federal Open Market Committee have been clearer than usual, and made sure to remove almost all stimulative effect from what could have been viewed as an historic first cut in a decade. Apart from the press conference: - The cut was only 25 basis points when there were lingering hopes that the central bankers would throw caution to the winds and cut by 50 basis points;

- two FOMC members, the normally hawkish Esther George of the Kansas City Fed and the normally dovish Eric Rosengren of the Boston Fed, chose to dissent, suggesting that winning consensus for further cuts would not be simple;

- and the Fed's official reasons for cutting started with a factor that is not even officially in its remit ("In light of the implications of global developments for the economic outlook as well as muted inflation pressures..."). This was a contingent cut, responding to "implications" of things that might affect the economic outlook, and plainly refers to the risks of a trade war above all. There is no mention of concern over full employment. So a diminution of trade pressures would on its own give the Fed cover to stop cutting rates.

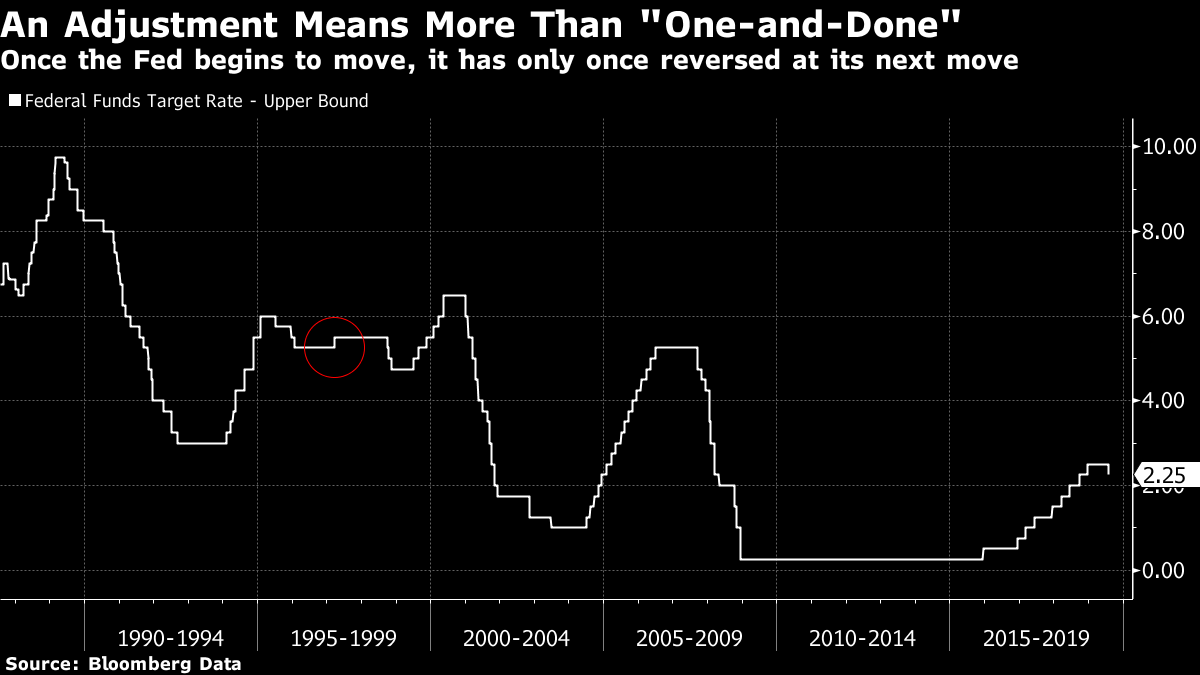

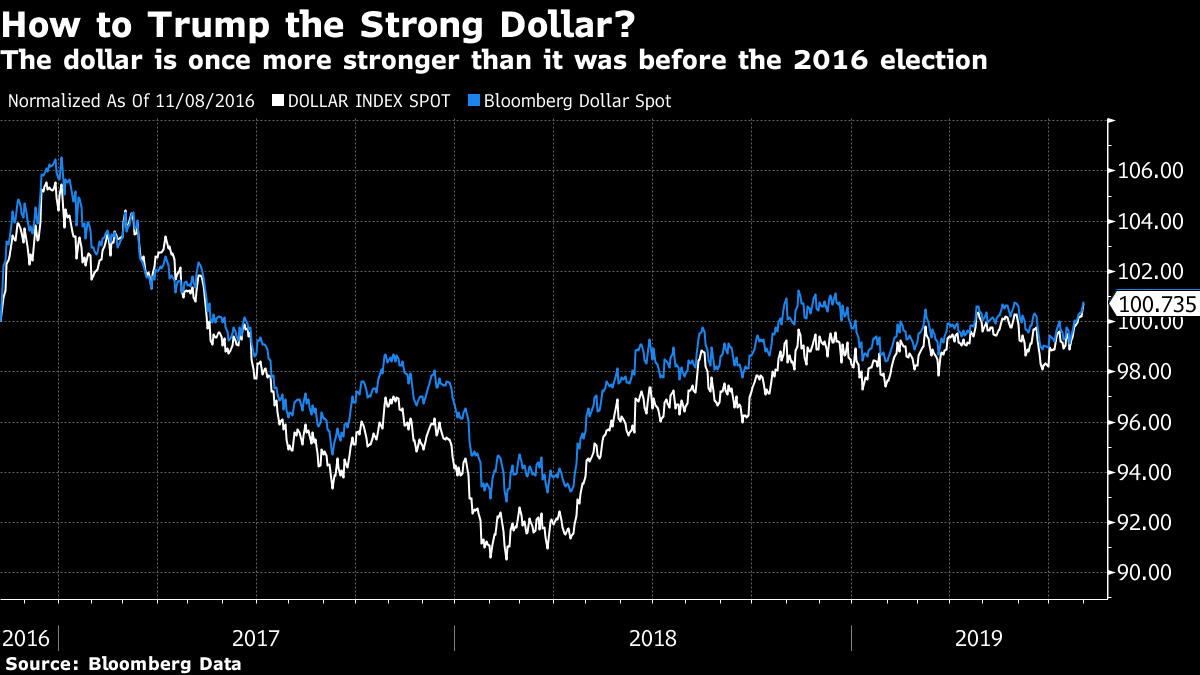

Against this, the FOMC staged a mild surprise by announcing that it would halt quantitative tightening – selling off bonds it previously bought in quantitative easing purchases – in August, rather than in September as originally scheduled. But the package as a whole was plainly meant to show that the Fed was cutting with reluctance and prudence, and not with any sense that a major recession was in the offing, or that many more cuts would be needed. As the economy is in strong shape, this seems eminently reasonable. Given the way investors were positioned, the Fed effectively had no choice but to produce a cut. To do otherwise would have risked a major tantrum. The cut was about as grudging as policy makers could make it. Some claimed that Powell's later assertion that further cuts were still possible was a backtrack or even a U-turn from his original assertion that he was involved in a "mid-cycle correction." I think that this is unfair. We will use the history of the Fed in the post-Paul Volcker era as a guide. A look at the federal funds target rate since Alan Greenspan took over in 1987 reveals that every time the Fed has changed direction, and started hiking after a period of cuts or vice versa, its next move has always been in the same direction. There have been mid-cycle adjustments before, but they have never involved a "one-and-done" cut. To be clear, there is one example of a "one-and-done" hike, from early 1997, which I have ringed on the chart. That was known at the time as the "Irrational Exuberance" hike, when Greenspan followed up on his warning of incipient stock market bubbles and raised rates, provoking a 10% decline in the stock market. On that occasion, the next move was down, after the Long-Term Capital Markets disaster of the following year. But the whole incident is now regarded as an egregious policy mistake, when the Fed started to try to stop the bubble from inflating but then lost its nerve – so the precedent again suggests that Powell's mid-cycle adjustment likely involves at least two 25 basis point cuts.  So there is a consistent message, which is that the Fed is not obligated to cut further and may not have embarked on any major campaign of cuts to avert a recession, but will probably cut at least once more before it is done. There is ample room to argue about whether it is on the right path. For now, look briefly at the reaction of markets, which had been set up for a campaign of rate cuts previously only seen at the onset of a recession, while not positioning for the recession – a strange combination to put it mildly. The operative markets here are in foreign-exchange and bonds. Stocks are at near-record highs and no self-respecting central banker should give a hoot about pushing their value down. But the level of the dollar has become important with the trade conflict, while bond markets suggest dangerous extremes of valuation that must be handled with extreme care. Treasuries saw their short-term yields rise and long-term yields fall in the sharpest flattening of the yield curve since before President Donald Trump took office. As a flat or inverted yield curve generally suggests that the Fed is too tight in the present, that is a good clue that the market is trying to pressure the Fed to continue its cutting. In the case of the gap between 3-month and 10-year yields, we returned to a full inversion, in what is generally regarded as a clear signal that a recession is coming.  Meanwhile, the dollar gained on all fronts. This is the single greatest problem for the Fed at present, and probably the most valid reason for the annoyance of a president who is trying to put pressure on U.S. trading partners. And, indeed, the Fed implicitly admits that this is one of the main reasons for cutting rates:  As for the tightness of financial conditions, if we define this as real long-term rates, subtracting long-term inflation break-even rates from long-term yields, we find that the Fed has not done anything to undo the radical loosening of the last year. This is the performance of real 10-year yields over the last 12 months:  That suggests the Fed got the balance right on Wednesday - so far. For the immediate future, the greatest causes for concern would be a continued rally for the dollar, or an accident in the bond market as yields rose significantly higher. Both would create great problems across the world. And it would be handy for Powell and the Fed, if the U.S. economic data, starting with unemployment numbers later this week, stayed strong – while many in markets will be rooting for poor numbers that would force the Fed to cut.

Again, Powell and his colleagues may feel as exposed as presidential candidates. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment