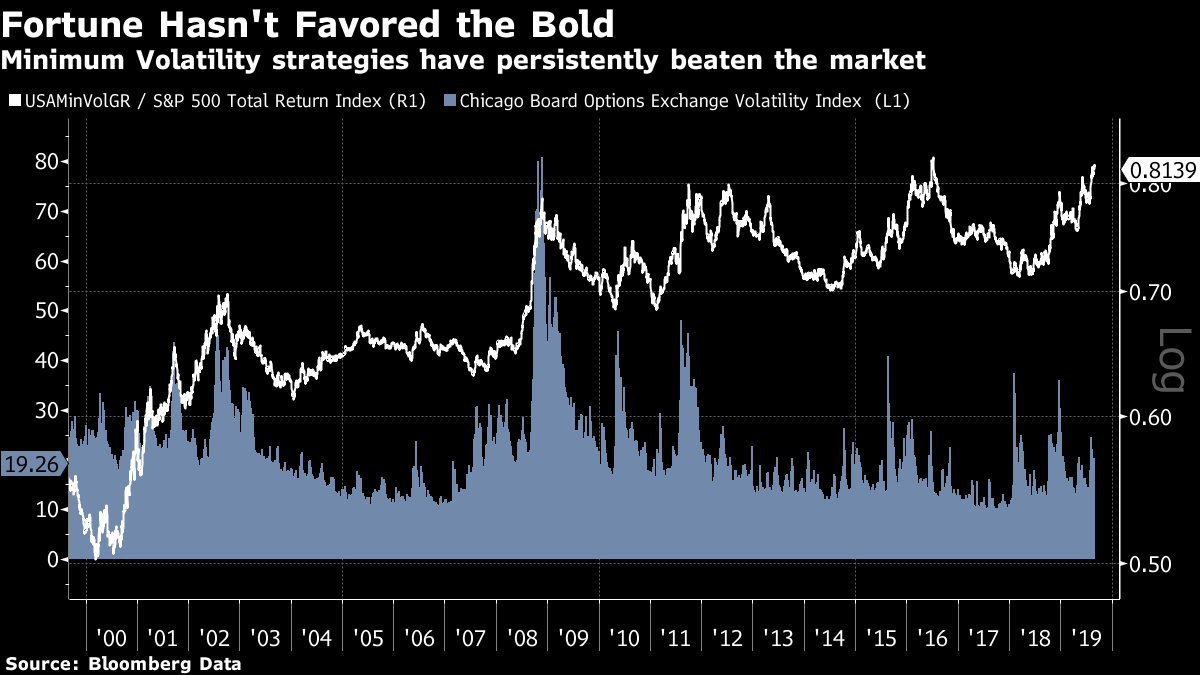

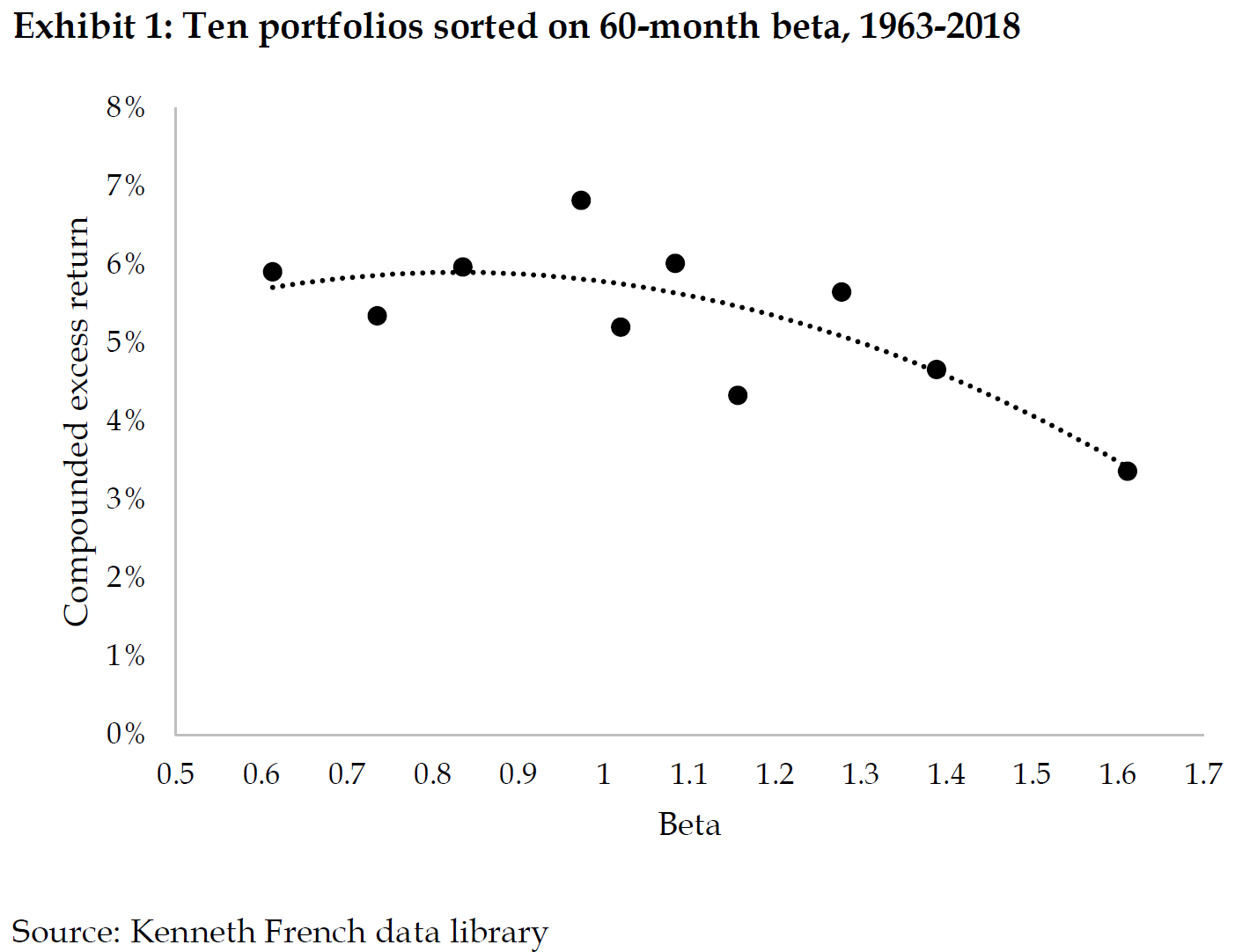

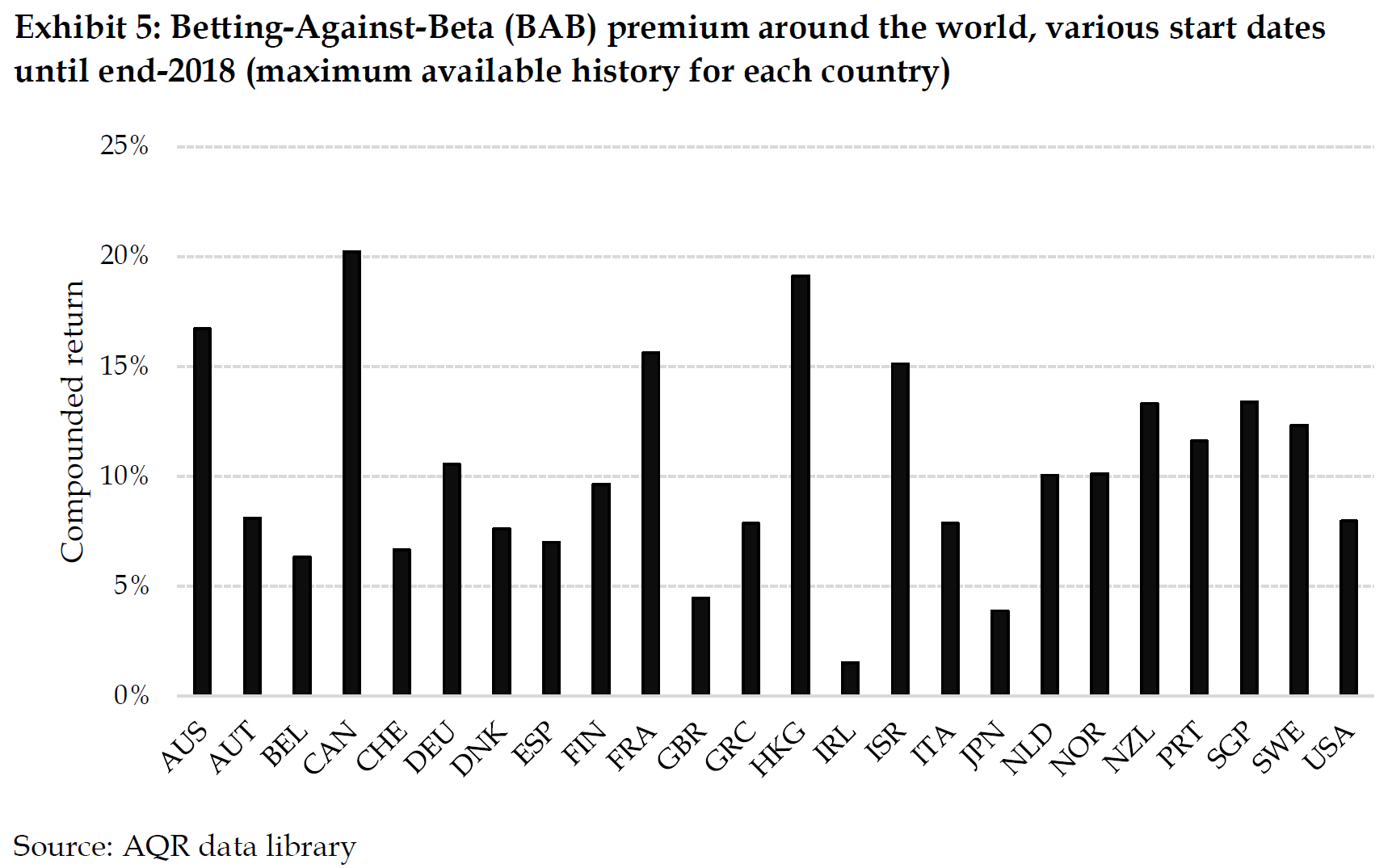

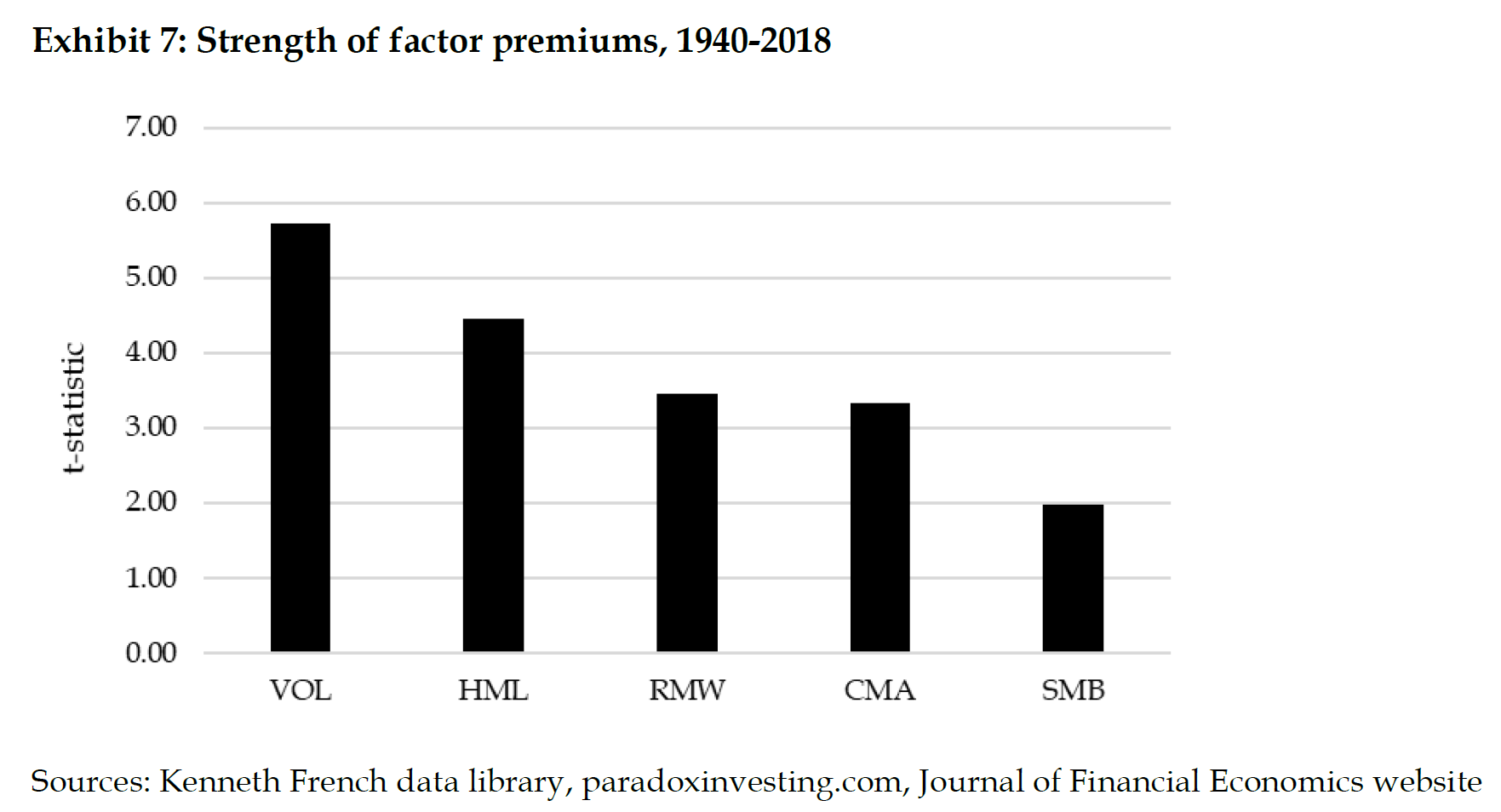

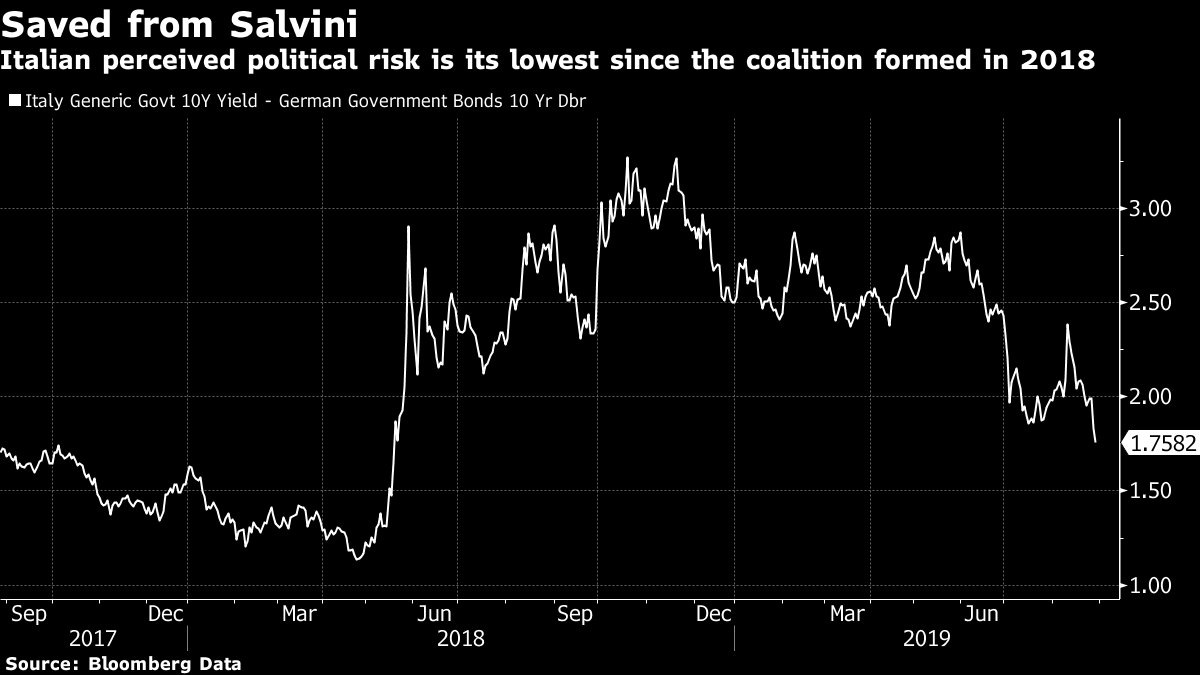

Less risk = more return. The most basic building block of modern academic finance is arguably that higher returns are a reward for taking greater risk. That is why stocks in the long run generate greater returns than less riskier investments such as corporate bonds, and why small entrepreneurial companies that strike it big deliver far more for shareholders than regulated utilities. The problem with this theory is that it does not work. As academics sift through the data for persistent anomalies that can predict which stocks will perform best, the clearest is that lower risk stocks tend to outperform in the long run. There is a relationship between risk and return, in other words, but that relationship runs in exactly the opposite direction to the way that we had all supposed. Since the financial crisis, there has been growing interest in low- or minimum-volatility strategies known as "Betting Against Beta." The idea has been turned into indexes that underpin a range of different exchange-traded funds, and it is being applied by plenty of active quant managers. To an extent, as is often the case with anomalies, the attempt to exploit this one started just as it stopped performing as well as it had in the past. This might be causal; if people think there is easy money to be made, they will pile into low-volatility stocks and thereby reduce the returns to be made. The strategy also had evident appeal in the aftermath of a major market bust. On such occasions, it strongly outperforms the rest of the market. When things are healthier, it tends to lag behind, but not by enough to eliminate its accumulated outperformance. The following chart shows the performance of MSCI's U.S. minimum volatility index relative to the S&P 500 Index on a total return basis, with the CBOE VIX index of volatility on a separate axis:  As might be expected, low-volatility stocks with the least sensitivity to the broader market have their moment of glory when the market as a whole is in a seizure, as happened in 2000 and 2008. And since the worst of the crisis, the MSCI index has performed in line with the S&P 500, with troughs during times of calm and recoveries during market scares. But even if low-vol enjoys its best moments at times of turbulence, there does seem to be something persistent there. That is the finding of a new paper availablehere called "The Volatility Effect Revisited," by David Blitz, Pim van Vliet and Guido Baltussen of the Dutch group Robeco Asset Management. They found high "beta" stocks – or those that are most sensitive to broader moves in the market and most volatile – did worst, while those that opted for the least variable suffered almost no loss of return. As lower volatility makes life far easier, this suggests that low-volatility stocks have powerful attractions. In this chart, based on data from the Kenneth French data library at Dartmouth University's Tuck School of Business, we can see that over the last 55 years there has been minimal penalty for holding boring stocks, and quite a severe penalty for holding the more volatile ones:  This is not just a U.S. phenomenon. The authors cite the following chart, based on data from AQR, the U.S.-based fund manager, showing that the strategy of "betting against beta," or choosing the stocks that are least sensitive to the market. The strategy has made money everywhere for which the data has been tested, and in most countries a low-risk strategy has done better than it has done in the U.S.  Over the long term, the authors also find that their low-volatility strategy, labeled VOL in this chart, has outperformed all the factors used by French and the Nobel laureate economist Eugene Fama in their famous methodology for breaking down the returns for stocks in terms of persistent factors.  You can find these factors explained here on French's website. In the chart, SMB stands for Small Minus Big (the size effect, in which small stocks outperform big ones); HML is High Minus Low, and refers to the value effect in which stocks with cheap valuations tend to outperform; RMW is Robust Minus Weak, the factor that companies with robust profitability tend to outperform; CMA is the investment factor, which favors companies that invest conservatively over those that are aggressive. This adds up to an impressive laundry list of reasons to take low-volatility investing seriously. Other findings are that the strategy is not yet being arbitraged away. If anything, hedge funds tend to pile into the other side of the trade and look for more volatile stocks, as this gives them a better chance of short-term outperformance, and their incentives are asymmetric. The professors also found, reassuringly, that the strategy benefits from low turnover. It can work without intensive trading. And there is even evidence that the behavior of investment institutions, desperate not to look bad compared to their peers, has also tended to strengthen the low-volatility anomaly over time. So, it turns out, the traditional approach of buying "widows and orphans" stocks in big, boring companies and holding them forever may have been a great idea after all. Who would have thought? The Italian Job. On the subject of taking risks, investors suddenly think that Italy involves far fewer risks than they used to believe. Yields on Italian 10-year government bonds (BTPs) are not negative, but they did on Wednesday manage to sink below 1%, an unprecedented level. After rising sharply last year amid horror over the governing coalition formed by the left-populist 5 Star Movement and the right-populist League, the Italian bond market has now joined the rest of Europe in plumbing new depths.  The reason for the relief is straightforward. Matteo Salvini, leader of the League and by far the most popular politician in Italy, appears to have overplayed his hand and now finds himself out of government. By breaking up the coalition, his plan was to force a new election in which the League would almost certainly have been the largest party, making it hard to stop him from gaining the premiership. Instead, the effect has been to force 5 Star and the center-left Democratic Party to hammer out a new coalition, which will even involve hanging on to the old coalition's prime minister, Giuseppe Conte. The new coalition is likely to be more moderate, and is far less likely to force a confrontation with the European Union over Italy's fiscal policy. As a result, the spread of Italian yields over equivalent German bunds, after spiking when Salvini broke up the coalition, is now the narrowest since the coalition first began to take shape in the summer of last year. Indeed it is almost back to the levels seen before last year's election, which was followed by months of horse-trading:  Are markets right to respond this way? Directionally, this is unquestionably a move that reduces macroeconomic risks, and buys some time. The possibility of a new Salvini premiership starting just as a Boris Johnson-led U.K. crashed out of the EU, and as Germany slumped further towards recession, was not something anyone wanted to contemplate. But markets may have taken things too far. Salvini remains the most popular politician in Italy, and his motivated supporters will now feel aggrieved that their prize has been snatched from them. He has a political style that works well in opposition, while 5 Star, already totally out-maneuvered by the League in its first coalition, has a style that appears deeply unsuited to governing. The arguments for a more expansive Italian fiscal policy remain strong, but this will continue to be incompatible with membership of the EU and the euro zone. The conditions are perfect then for a charismatic right-populist politician to make hay in opposition. Time has been bought, which is valuable. It helps both Italy and Europe as a whole. But the longer-term prognosis is little changed. |

Post a Comment