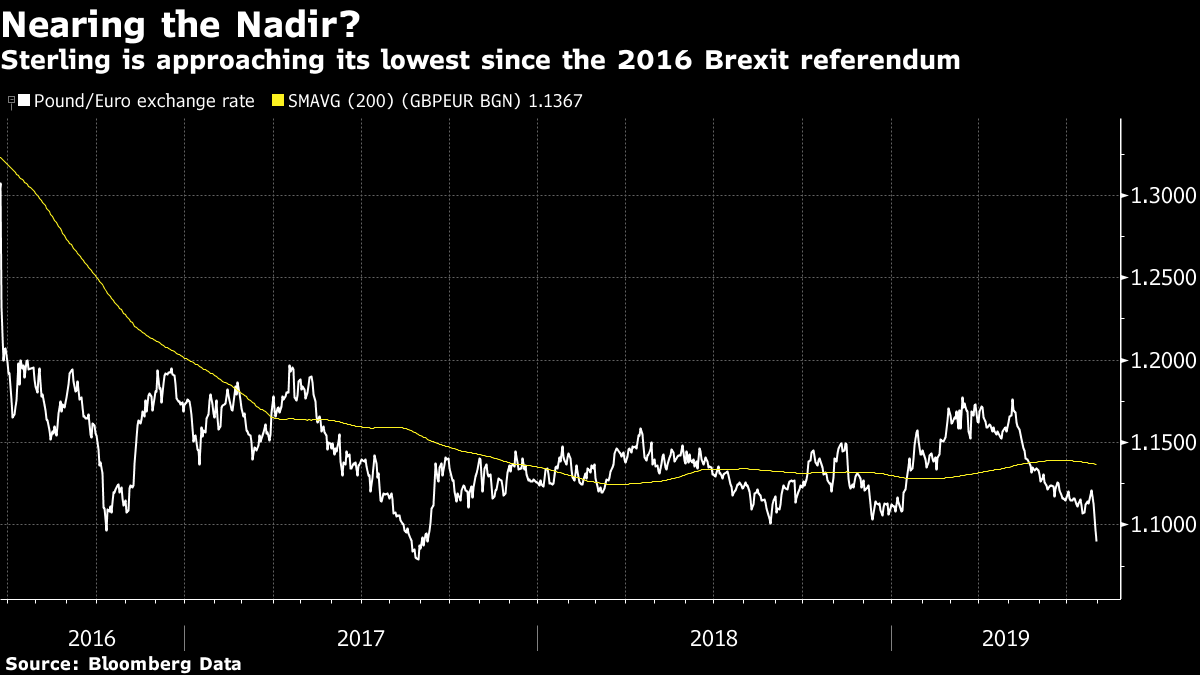

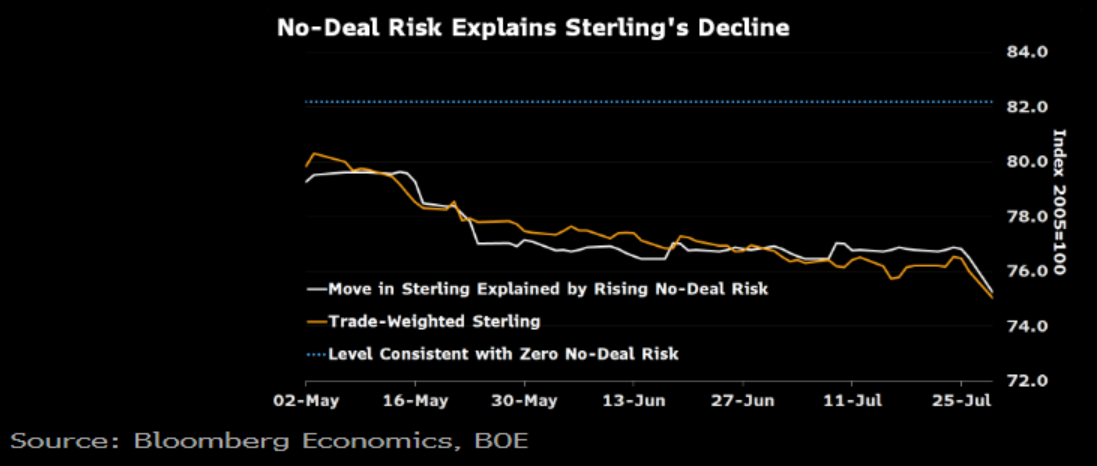

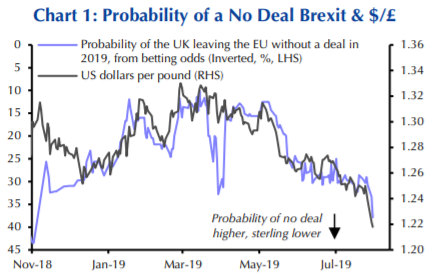

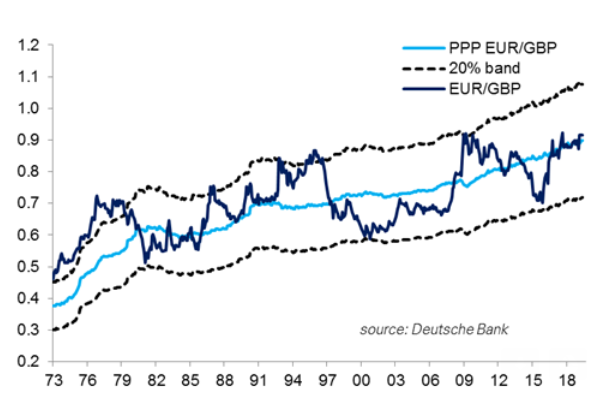

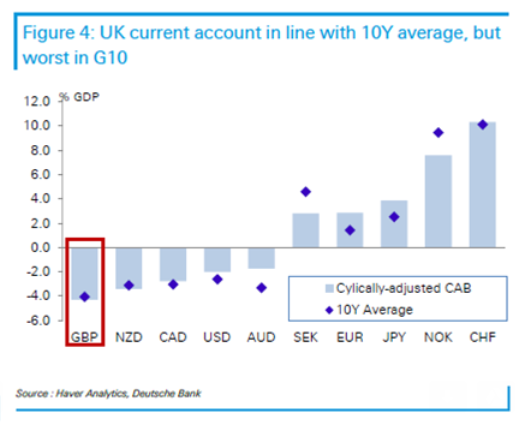

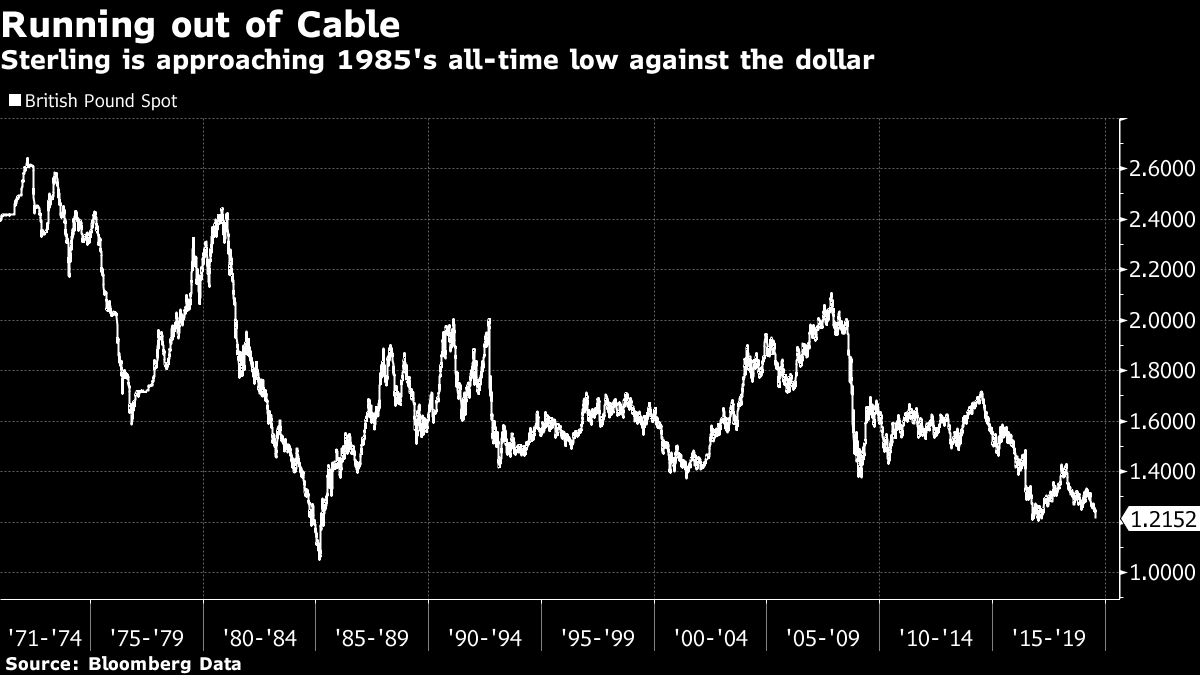

BoJo versus GBP: Clash of the Titans. Boris Johnson's greatest political weapon is his self-confidence. Even more than his charm or his intellect, it is his boundless belief in his ability to get things done that has accompanied his rise to Prime Minister of the U.K.. He never wavers, at least in public, and never betrays a shred of self-doubt. Opponents not already disarmed by the famous Johnson charm or sense of humor often find this impossible to counter. However, knowingly or not, Britain's new prime minister is now setting up the hardest fight of his career. It is not with any politician, who might be awed by the confidence that an Eton and Balliol education infers, but rather with the foreign-exchange market. That could be a problem. Currencies are immune to personal charm. And they have a history of humiliating British prime ministers, even the greatest of them. For both the pound sterling and for Johnson, Brexit – Britain's already delayed exit from the European Union – is all-important. For the markets, the critical point is that Britain should not leave the EU without a deal with the remaining members. Such a scenario would leave the U.K. at the mercy of tariffs dictated by the World Trade Organization. This would undeniably lead to much initial chaos and the U.K. trading on far worse terms with its biggest partners, although there is room for argument over how long and serious the disruption would last. For months now, anything that increases the chance of a "no deal" exit has damaged the pound and anything that reduces "no deal" risk has raised it. Johnson says, doubtless truthfully, that he would prefer to leave the EU with a negotiated settlement. He is on record from the referendum campaign three years ago saying there would be no difficulty in reaching such a deal. But making a deal is not his priority. A large proportion of the U.K. population, and a strong majority of the ruling Conservative party's voters, are angered that Brexit has already been delayed, and are determined that Britain should depart on the current scheduled date of Oct. 31. With the rival Brexit Party now positioned to scoop up all these votes should the U.K. prolong its membership, meeting that deadline becomes an existential issue for Johnson and for the Conservatives at large. In this particular situation, he is working on the assumption that failure to exit on time would do much worse damage for his party than would the severe economic problems that would follow a "no deal" exit. He is almost certainly right. With only three months until the deadline, negotiating a new deal would be prohibitively difficult. It is complicated enough as it is, and would need the assent of all the EU's members. It is simply not going to happen. So the two choices are "delay" (the worst outcome for Johnson) or "exit with no deal" (the worst outcome for currency markets). It is possible that Johnson is involved in a high-stakes game of chicken to force the EU to negotiate. The critical issue is the Irish border, which must remain open under the Good Friday Agreement that ended the Troubles in Northern Ireland, but which would have to close if the U.K. left the EU without a deal. Johnson's gambit is that he will refuse to talk to EU leaders until they agree to remove the "Irish Backstop" – the measures agreed by his predecessor Theresa May to ensure that the borders remain open. The backstop was originally requested by the British, and it is the British – not the other nations – who have refused to ratify the May agreement including the backstop. It might therefore seem obvious that it is incumbent on the British to restart negotiations with their own alternative to the backstop. So why is Johnson saying that it is up to the EU to come up with an alternative, and that if they fail to do so they would take the blame for a subsequent "no deal" exit? There are two solutions, which are not mutually exclusive. One is that his confidence has turned to over-confidence, and he truly believes he can force concessions. The other is that he regards a "no deal" exit as already inevitable, and is making an attempt to blame it on someone else. Any bad economic fall-out at the end of this year will be the EU's fault, not his; or that at least is the story he is trying to tell. Either way, the risks of a "no deal" exit, estimated by Johnson at one-in-a-million, or 0.00001% during his leadership campaign earlier this month, now look much higher. As his Brexit enforcer Michael Gove has publicly described "no deal" as a working assumption, that would imply a chance of more than 50%. Now we come to sterling. When governments control their own currency, no other market counts. Government bond prices do not necessarily fall in response to a growing risk of default. Instead, a collapsing currency means that it has in effect defaulted on its promises to lenders by a different means. And sterling has plainly reacted very negatively to the growing chance of "no deal" in the last few weeks. This is how sterling has moved against the euro, its biggest trading partner, since the Brexit referendum in 2016:  This raises two vital questions: 1) Exactly how bad for the pound does the market see a "no deal" exit as being? And 2) what chance of this happening is currently embedded in prices? Whatever Johnson may confidently say, it is clear that markets think "no deal" would be bad, and that the chances of it happening have long been higher than one in a million. Beyond that, strategists have tried all kinds of models to answer the question. I will mention two. First, Bloomberg U.K. economist Dan Hanson estimates that sterling could fall an additional 13%. This is because for every 1 percentage point increase in "no deal" risk, trade-weighted sterling falls 0.2%. According to the bookies, no-deal risk could yet rise 65 percentage points before it reaches 100 (rather generous odds, I think), and so a 13% drop is possible. Hanson's model simply regresses moves in "no deal" probabilities expressed in betting odds against sterling and the result is spectacular:  London's Capital Economics conducted the same exercise for the dollar-sterling exchange rate, and found that for every 10-percentage-point increase in the chance of "no deal" equates to the pound losing 3.5 cents on the dollar. So if there is really still a 65% chance of "no deal," sterling stands to drop an additional 22 cents or so. And this would bring it almost exactly to parity with the dollar for the first time ever. Capital Economics' chart also shows a startlingly strong fit with market expectations of "no deal" ever since May lost control of the Brexit process at the end of last year. The markets could not be clearer in their message to U.K. politicians that they think "no deal" would be a bad idea.  "No deal" on these measures begins to look like a trap door beneath the pound. Is this overdone? Has the pound been made too cheap compared with its fundamentals? It is maddeningly difficult to come up with an intrinsic or underlying value for a currency. But if we go with the rate needed to maintain purchasing power parity between two currencies (itself very difficult to measure), then this chart from Deutsche Bank strategist George Saravelos suggests the pound weaken much further:  Meanwhile, Saravelos also shows that the U.K. current account now appears to be the weakest among the major currencies. If the U.K. really is better able to negotiate preferential trade deals once it is outside the EU, this could change. For the time being, it suggests more weakness:  So there is no obvious safety net to arrest sterling's fall. If we look at the real effective exchange rate for sterling (taking into account how much the rate should adjust for different levels of inflation in different countries, as calculated by JPMorgan,) we can see that sterling needs to drop only about another four percentage points to reach its lowest since the series began a quarter century ago:  On this valuation measure, sterling looks quite cheap, while falling much further would bring some major technical levels into question - always an important factor in the foreign-exchange market. There is a broadly similar picture if we look at the relationship between the dollar and the pound going back to when U.S. President Richard Nixon took the dollar out of the old Bretton Woods agreement and effectively allowed the pound and dollar to float against each other:  Against the dollar, sterling is on the verge of taking out its post-referendum low, after which the only significant landmarks left would be the low set in 1985, a few months before finance ministers agreed in the Plaza Accord to limit the strength of the dollar and then, only a few cents lower, parity with the dollar. To go much lower than this will involve something truly historic, in other words. And declines to these kinds of levels have never lasted long in the past; "no deal" could very swiftly create an epic buying opportunity, but only once economic destruction has been wrought. Johnson should be aware that the currency market has almost untrammeled ability to humble British prime ministers. At least two prime ministers effectively lost their jobs over disastrous declines for sterling – Labour's Harold Wilson, who devalued the pound during the fixed exchange-rate era of the 1960s and vainly tried to tell the British public that "the pound in your pocket" had not changed, and the Conservative John Major, whose reputation for economic competence never recovered from the pound's disastrous crash out of the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992. And not even the greatest prime ministers were immune. The pound's all-time low came more than five years into the revered premiership of Margaret Thatcher, who famously said that you can't buck the markets. In one of the most embarrassing incidents of her time in office, she failed to tell her press officer that she was prepared to U-turn on this idea, leading to quotes that knocked the bottom out of the currency early in 1985. Turning the pound around required boosting interest rates all the way up to 14% later in the year. That incident led to a falling out with senior colleagues over whether the pound should join the exchange-rate mechanism, an effective try-out for the single currency, and it was due to this issue that she was finally ejected from power. This could be one occasion when the famous Johnson self-confidence turns into a liability, rather than an asset. If Thatcher could be bested by the currency markets, there is every reason to fear that the same fate could befall Johnson. And the currency market could yet challenge his assumption that his imperative should be to leave, "do or die." At present, his plan seems to be that he can blame any resulting economic mess on the EU. But that has been tried before and did not work. Wilson complained of the "gnomes of Zurich." Major could complain of the machinations of George Soros. Both took the electoral blame. And there comes a point where British pride in leaving the EU – plainly hugely important for a big chunk of the population – could be eclipsed by the currency market. The symbolism is meaningless, but the pound is worth more than a single unit of any other major currency. This has always been so, going back to the days of Empire. This means nothing. Even if there are more than a hundred yen per pound, this tells us nothing about the relative strength of the British and Japanese economies. But British people are not used to the idea that one of anyone else's currency is worth any more than one pound. Breaching parity against the euro or the dollar would be an easily understood and humiliating event. The politics that might follow in the wake of such an event are impossible to predict. Any number of different players might take advantage – although the conventional Conservative party would be unlikely to survive. Johnson is obviously confident that he can avert such an event, or deal with its consequences if it comes. At present, it looks alarmingly as if he is over-confident. As Thatcher could have told him, you can't buck the market.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment