Red Flags: Reading Notes Something's happening in Hong Kong, and so the world's attention is turned to China once more. But most of us cannot turn our attention away from it for a minute anyway. It has provided most of the world's economic growth for a generation, and now it is on the opposite side of a conflict with the U.S. that threatens to define the world for the next generation as clearly and as damagingly as the Cold War conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union once did. That is why I am proposing "Red Flags: Why Xi's China is in Jeopardy" by George Magnus as this month's selection for the Bloomberg book club. It was published last year so should still be easy to find. We are aiming to have a live discussion on the terminal by the end of July. For now all contributions and comments are greatly welcome. You can send emails to authersnotes@bloomberg.net or join in conversation in the IB chat room on the Bloomberg terminal. (If you do not already have access, send us a request at that email address). So, why this book by George Magnus? For those who do not recognize his name, Magnus was an economist and foreign exchange strategist at some of the biggest banks in the City of London for decades. He has now transitioned to being an academic, based at Oxford, and has continued to pursue the questions about China that interested him when he was sitting in trading rooms. Apart from being a great and wise analyst, he also brings exactly the frame of reference on China that many readers of this newsletter will have from their daily working lives. Particularly with the trade dispute at the top of the agenda, it is easy for debates surrounding China to grow over-emotional and ideological. Magnus's book is, I think most will agree, incredibly alarming. But it is based on fact and dispassionate throughout. It also, I hope, will allow us to have a more structured discussion about it over the next few weeks. Let me set out Magnus's argument and the questions he is raising. This is my own summary, but I am keeping close to the outline in the book. The key points: - President Xi Jinping is different. Mao's was one model of China. Deng's was another. Now Xi has a new model for Chinese growth.

- Extrapolating growth is over. We can no longer extrapolate the growth rates of the last three decades into the future.

- We must abandon the assumption made almost universally in the west, and widely in China, that the country was heading for a liberal and democratic western model.

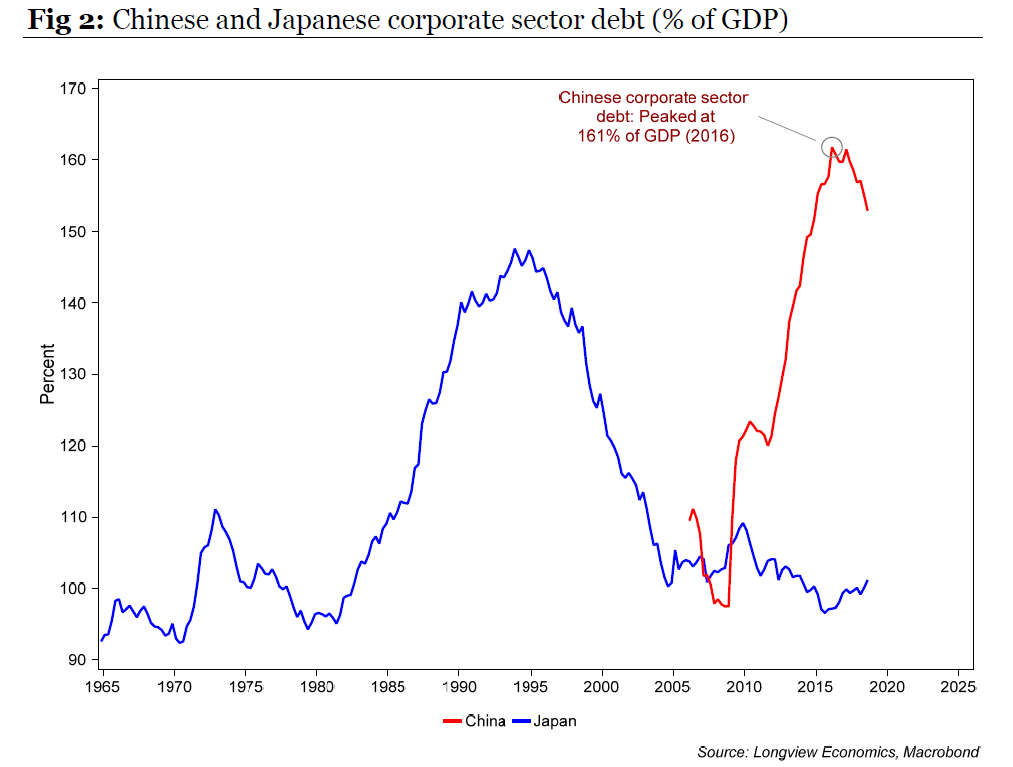

This is not a cheerful read, therefore. And note that I have so far made no mention of the U.S. or trade policy. Now we come to the "red flags" of the title, or the traps that could thwart China from growing. They are: - The Debt Trap. China's leverage has shot up since the crisis.

- The Renminbi Trap. Controlling the exchange rate while allowing more capital to flow in and out of the country grows ever harder. How will it be resolved?

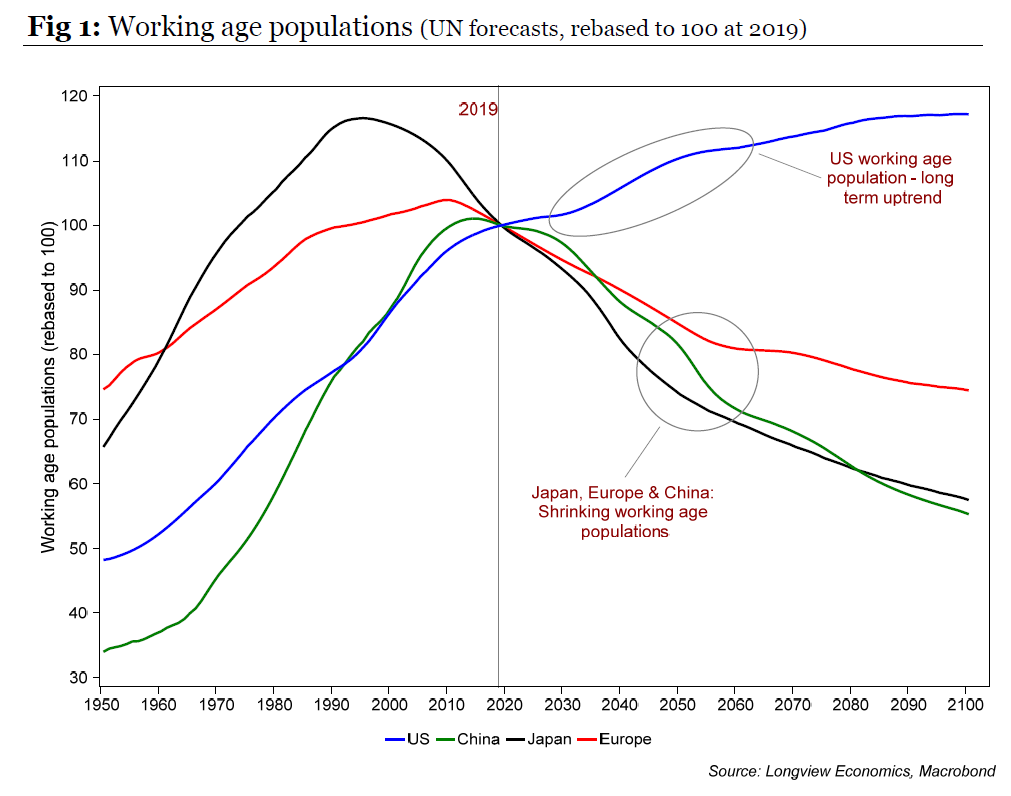

- The Demographic Trap. Like Japan, China is aging, and its era of urbanization is approaching an end. This could act as a brake on growth.

- The Middle-Income Trap. Plenty of other countries have grown fast. But escaping from the ranks of middle-income countries to reach fully developed status without suffering a major economic crisis along the way has proved elusive. Can China really evade this fate?

From these traps, Magnus tries to look at Chinese international ambitions, including the Belt and Road Initiative, and whether they involve an inevitable conflict with the west. And throughout, there is the underlying contradiction implied by its embrace of capitalism and the profit motive, while clamping down ever further into an authoritarian model of governance. We cannot say that this is impossible. But it will be extraordinarily difficult. This quote from the introduction sums up the problem:

Xi's intention is to show that an authoritarian, even dictatorial China can switch its economic agenda seamlessly away from high growth and malinvestment towards greater equality, a better environment, financial stability, OECD-type wealth status, and global technological leadership. … If it happened, China would be the first authoritatian country or dictatorship to do so. A Reading Plan I suggest we discuss these issues as Magnus raises them. So for next week, let's try to read his coverage of China's remarkable economic and political history up to Xi, which shows that Xi represents a change and also that he is harvesting a long history. China endured a century of humiliation before the arrival of Mao Zedong after the war. They have a great effect on Xi's inheritance and also on what is politically possible for Chinese leadership as it confronts the U.S. I found this passage telling: The Chinese founding narrative of shame and suffering at the hands of foreign powers is about loss and legitimacy. It is about the loss of territory, of which Taiwan is the only part yet to be returned to the motherland. It is about losses that are even more sensitive, namely of control over the domestic and external environment, and of dignity in the world. It is also about the fundamental legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party, which is portrayed as the only political organisation that could stand up to foreign aggression, and must therefore be relied upon as a guarantor of China's security and pride.

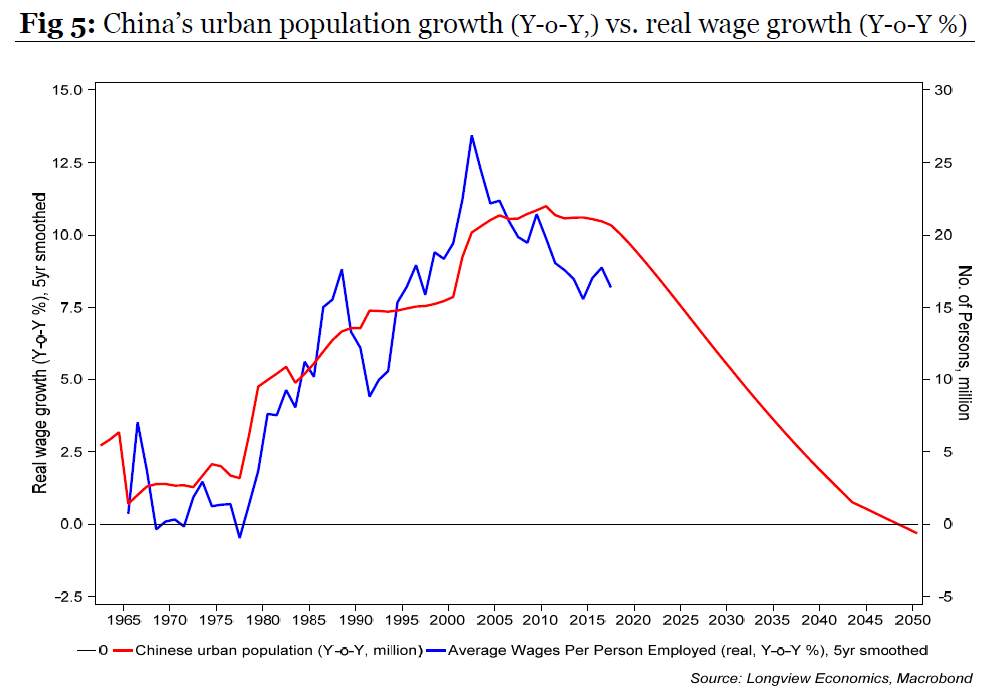

Many in the U.S. feel that China's current underlying economic weakness will force them to capitulate to U.S. trade demands. As Magnus makes clear here, it will be much harder than that for the Chinese leadership to stand down. Reader, read on. And let us discuss how China is likely to behave in the trade dispute and how this should inform American behavior. Extra numbers: I am hoping to include guest commentary as we continue. For now, I think it is worth emphasizing that the scale of China's demographic issue is underappreciated. These charts are from Harry Colvin of Longview Economics of London and demonstrate the problem clearly. First, China's demographics are about to turn as drastically adverse as Japan's. Its working age population has peaked and started a decline that from now on will be as steep as the one in Japan (which, of course, has seen worsening demographics for many years now). China's demographics are on course to be far more problematic than Europe's:  For another uncomfortable comparison with Japan, this is Chinese corporate sector debt as a proportion of GDP, compared with Japanese history. Just because Japan engaged in a similar borrowing binge that then reversed does not of course prove that the same thing will happen in China. But it certainly qualifies as a "red flag":  Another problem for China is that the long process of urbanization, which powered its growth, has peaked. Without the huge flows of workers from the provinces eagerly powering Chinese industry and creating a middle-class marketplace, growth will be far harder. It will also grow more difficult to maintain growth in real wages, which is an important part of the Communist Party's compact with the people — that they must do without democracy but will receive growth in return.  Extra Listening: For those of you who enjoy podcasts, Magnus has taken part in a few interviews about his book that are well worth downloading. He talked to my former colleague Cardiff Garcia on whether China will inevitably overtake the U.S. as the world's biggest economy for NPR's The Indicator podcast. He also talked to my current colleagues Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal on Bloomberg's Odd Lots podcast. You can also listen to him talk to James Pethokoukis on the American Enterprise Institute's Political Economy podcast. Extra Reading: Most Bloomberg clients do not have a lot of time for reading, and I am recommending "Red Flags" because it covers the main themes around China in an up-to-date and manageable form. If you have particular interests, there are plenty of other entries in the burgeoning China literature. For the Trump administration's guiding philosophy, try "Death by China" by Peter Navarro (also a movie, narrated by Martin Sheen, that can be found on YouTube here). Navarro is one of the few ever-presents in the Trump White House, and his views should therefore be given much weight. He has the ear of the world's most powerful man — and this book and movie show that Navarro is an extremely skilled polemicist. For the power of the Communist Party, and the priorities confronting its leaders, read The "The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers" by my former colleague Richard McGregor. It is already a classic and explains how the party exerts its control. To understand what Magnus would call the "Era of Extrapolation," I would recommend "China Shakes the World," by another former colleague, James Kynge. I think it is fair to argue that China has now moved on from the stage of development that Kynge described brilliantly in these pages, but it is still worth reading.

Turning to broader foreign policy, one of the most alarming books of recent years was "Destined for War" by Harvard professor Graham Allison, which asks whether China can avoid the "Thucydides Trap," which holds that a declining dominant power and a rising new power are doomed to come into conflict.

"The State Strikes Back: The End of Economic Reform in China?" by the veteran Sinologist Nicholas Lardy also looks at China's statist move under Xi, covering similar ground to Magnus.

And for a sobering reminder that people have been predicting the downfall of China for a long time, armed with plenty of evidence, and that China keeps evading the moment of reckoning, you might look at "The Coming of Collapse of China," by Gordon Chang (who went on to co-write books with Peter Navarro). It was published in 2001. This is from the blurb:

"Peer beneath the veneer of modernization since Mao's death, and the symptoms of decay are everywhere: Deflation grips the economy, state-owned enterprises are failing, banks are hopelessly insolvent, foreign investment continues to decline, and Communist party corruption eats away at the fabric of society. Beijing's cautious reforms have left the country stuck midway between communism and capitalism, Chang writes. With its impending World Trade Organization membership, for the first time China will be forced to open itself to foreign competition, which will shake the country to its foundations. Economic failure will be followed by government collapse." In understanding China, as with much in investing, timing is everything. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment