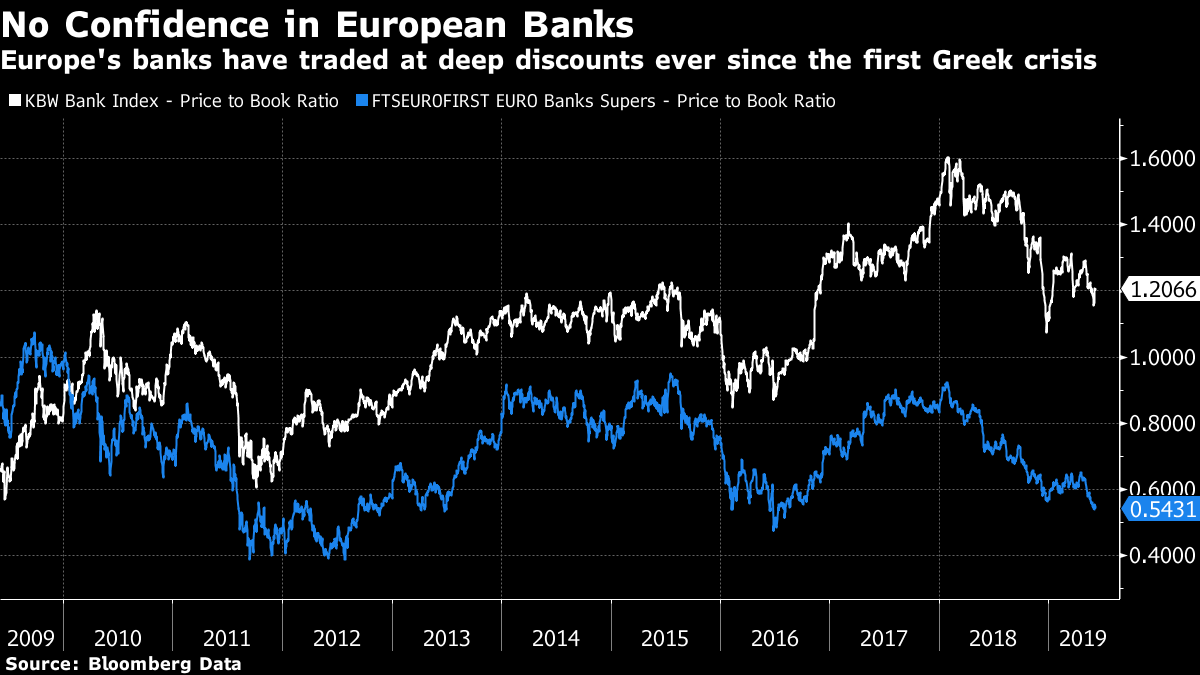

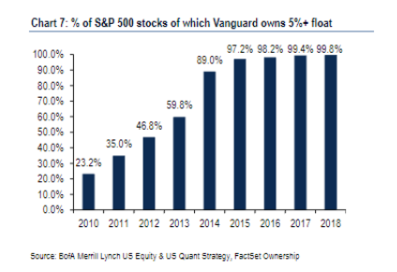

Max Headroom to do whatever it takes. When European Central Bank President Mario Draghi speaks, markets usually take notice. Back in 2012, he effectively ended the euro zone's sovereign debt crisis by promising to do "whatever it takes" to protect the euro. His words were so effective that the market never tested his resolve. The crisis abated, even as the economy went into a long and slow malaise. On the face of it, his comments after the ECB monetary policy meeting Thursday, held this month in Lithuania, were almost as aggressive as those he spoke in 2012. He was obviously determined to convince all that he was prepared to be far more dovish if necessary. He even suggested that he had "headroom" to resort to more quantitative easing, or bond purchases, if necessary. And yet the market did not take him all that seriously. The euro somehow strengthened against the dollar, exactly the opposite of what should happen when a central banker hints at interest rate cuts. This is partly because Draghi is half way out the door, as Bloomberg Opinion columnist Ferdinando Giugliano put it. It is also because the ECB is running out of ammunition. Rates are already low, and its balance sheet is loaded. It does not have anything like as much freedom of movement as the Federal Reserve. The need to do something is clear enough. The euro zone's economy has not lagged behind the U.S. as badly as many believe since the single currency came into being in 1999, but the latest dip, while the U.S. is gaining strength, is concerning.  Another problem is that inflationary expectations appear to have become untethered. The German bund market is signaling inflation of less than 0.8% per year over the next 10 years. This is lower than at any point when the sovereign debt crisis was at its height, from 2010 to 2012, and approaching its lowest since the euro's inception. The ECB has another deflation scare on its hands:  The Achilles heel responsible for Europe's relative weakness is its banking system. The price-to-book multiple that shareholders pay for bank shares is as good an indicator of this as any. Ever since the first Greece bailout crisis broke out in early 2010, European banks have traded at a discount to their book value, and a big discount to banks in the U.S. This explains why the ECB needs to keep propping up the banking system with targeted help. But as it wants to avoid moral hazard, that help cannot be too generous, which is why I found the plans for the latest "TLTRO" loan program to shore up banks rather unconvincing.  There is a decent argument that pessimism towards the euro zone has become excessive. But with the real possibility that we will have to wait months to learn the identity of Draghi's successor – he is due to leave at the end of October, just when the U.K. is due to leave the EU – there is a nasty tail risk from the euro zone to look forward to over the summer. Shareholder activism: A deep dive with Jeff Gramm. We enjoyed a Bloomberg Live blog chat with Jeff Gramm on Thursday to discuss his book Dear Chairman, the second selection in the Authers' Notes Bloomberg book club. We delved deep intocorporate governance and the entire transcript can be found on the terminal. For now, you might be interested in some of the following dialogues. He was talking with me and breaking news editor Madeleine Lim: JA: The first question is from John Tolis via the IB chat room. Do you think there is a positive effect of shareholder activism on long-term firm value? JG: I think in the end, shareholder representation on boards of directors is incredibly valuable. But I can't honestly say that the majority of recent activist campaigns have added value. I have to admit, a lot of recent activism at larger companies hasn't gotten me excited from an investment perspective. At small companies, there are still tons of situations with terrible governance that need some kind of remedy. ML: Hmm... But Jeff, you do say in your book that shareholder activism has had the biggest impact on changing corporate behavior in the past 100 years.... So not necessarily to the good of things? JG: I think in general that the threat of activism, the increased sophistication of large passive investors, and the fact that boards and CEOs are held accountable in a way that they were not 30 years ago, is very healthy for markets. JA: Here is another question that intrigues me. If you are an activist, what approach will work best in a world where Vanguard has a 5% stake in virtually every company in the U.S.? This chart from BofAML shows the scale of the issue:   Does this mean that we should look more closely at the proxyteers' tactics, as it is only through proxy voting, rather than through selling their stock that today's biggest owners are going to make their opinions felt? Does this mean that we should look more closely at the proxyteers' tactics, as it is only through proxy voting, rather than through selling their stock that today's biggest owners are going to make their opinions felt?

JG: Activist campaigns need to resonate with all the major holders, so in a world where Vanguard and Blackrock own huge percentages of virtually every company, the activist needs to appeal to them . This is actually a very interesting ecosystem. I recently was involved in a proxy fight where Vanguard, Dimensional and Blackrock, three massive, passive, indexing type firms, owned about 15% of the company. . . Each of them has their own process for evaluating activism, and they are not necessarily all aligned together. In fact, in this particular case, each firm voted slightly differently. If you think about Vanguard's position in the market, they have a huge incentive for markets to have integrity. In a sense, because of their dominance, the only thing that can slow down their juggernaut is if markets lose integrity for investors (ie, lots of Enrons happening). So Vanguard has this incentive to really focus on governance and try to be good stewards. And they have invested resources in doing so. But does this necessarily mean, they will view stocks in the exact same manner as an active manager who meets management every quarter, etc. So I think in general the incentives are *close* between index funds and lots of active managers, but not identical. And, to me, Blackrock is a manifestation of a problem with that slight misalignment. Blackrock has probably invested the most in stewardship, has the largest team, puts a lot of effort into presenting itself as progressive on stewardship, but I think in the end, and I am biased here from being on a losing end of one of their votes, they have cast some pretty bonkers votes. Beyond the issue of growing passive power, there is also the phenomenon of ESG – environmental, social and governance-driven investing. Gramm said: "Remember activism is often about capitalizing on shareholder discontent to make change. And if passive investors get more focused on ESG issues. . . You will see more activism highlighting those issues." That led to this exchange: ML: Jeff -- just quickly back to ESG: would you say evil hedge funds are cloaking themselves in ESG to get what they want? JG: I make the point that activist hedge funds are economic actors out to make a buck on their investments, just as Icahn and the corporate raiders were before them, and the Proxyteers were before the raiders. I think the neutral way to frame it would be, activists use tools at their disposal to make changes (which they believe are needed) to board of directors. Increasingly, one of those tools is ESG. So your characterization is, yes, basically correct. There is much more on the terminal for those who want to wade through the transcript. I encouraged all to dig in. Equality FC.

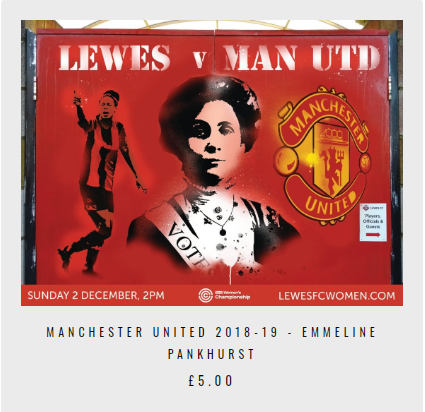

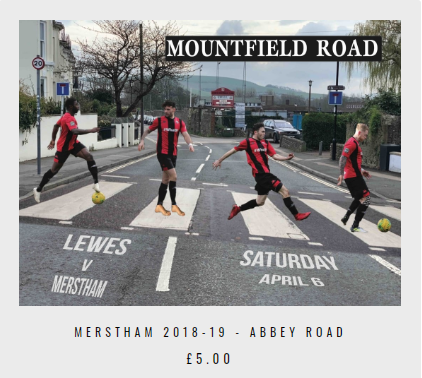

The other highlight, as far as I was concerned, was the revelation that Gramm is a shareholder in Lewes Football Club, nicknamed the Rooks. They are so called because there is a large rookery near their ground, which is called "The Dripping Pan." It happens to be next to my old high school, so I walked past it every day for four years. Whoever designs the club's posters, which can be found here, is a genius in my opinion. What follows, like the image of suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst above, is a poster for a game. It gives you a perfect view of my old route to school, which is in Mountfield Road:

Lewes, for the uninitiated, is the market town in southern England that gave the world Thomas Paine, and is best known for its tradition of burning the Pope in effigy on Nov. 5 each year. (A number of Protestant martyrs were burned at the stake by Queen Mary I, almost 500 years ago, but the tradition persists.) The men's team toil in the equivalent of the minor leagues, and have never reached the Football League proper. One does not generally expect a hedge fund manager from Texas to have shares in such a club.

However, there is something a little special about Lewes FC these days. It is community-owned, which turns out to be a great form of corporate governance. And continuing the town's commitment to revolutionary concepts of justice, it now calls itself Equality FC, because of a revolutionary policy. This is a statement of principle from the Rooks' website: "In 2017, we became the first (and only) club in the world to treat its women's and men's teams equally. Same budget. Same stadium. Same facilities. Same support. Same everything." Good for them. As a result, the women finished ninth in the FA Women's Championship this year, which was won by Manchester United (who are a bit better known). It is amazing what goes on at the Dripping Pan. And it is amazing what happens when companies commit to gender equality. Bloomberg's own executives enthusiastically back the 30% Club, which aims for 30% female representation on boards, while Gramm himself suggested that 50% representation would be an "excellent outcome" and "churn a lot of old, tired boards of directors, which might be a good thing." And if you want to support Lewes' fine commitment to women's sports, you can easily join them online for a very small fee. Or you could just buy a tea-cup.  |

Post a Comment