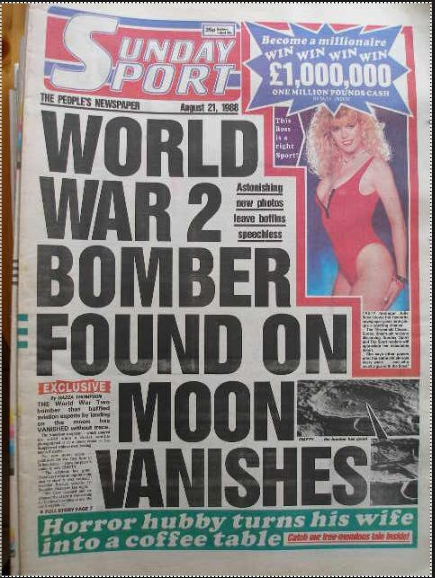

| World War II Bomber: An update. Yesterday, I suggested that the cancellation of tariffs on Mexico was akin to the famous tabloid headline "World War Two Bomber Found on Moon Mysteriously Disappears". There hadn't been a bomber on the moon in the first place, so this wasn't really news – and in the same way, I argued, the cancellation of the Mexican tariffs shouldn't be taken as a big deal as they were never a credible threat in the first place.

I now have to make a correction. I got the bomber headline slightly wrong. My thanks to Deon Gouws for finding a copy of the Sunday Sport's follow-up front page to its exclusive revelation that there was a bomber on the moon. Here it is:

I am glad to put the record straight. Meanwhile, markets have indeed taken the news of the cancelled Mexican tariffs only slightly more seriously than they should take the Sunday Sport's headline. Stocks have recovered a bit, but not by much. Mexican assets have adjusted, but beyond that, it was an underwhelming response. As for the sharp negative response in the bond market, with yields rising, that may be more of a reflection of concern that the Federal Reserve is now less likely to cut rates than any great relief about the economy.

Rather than delve into the markets' hopes and expectations for a "put" from either President Donald Trump, or Jay Powell of the Fed, I would like for now to focus on the other international ramifications. First, the negative attitude toward Chinese assets continues. This is how MSCI's index of the 100 companies in its World index with the greatest exposure to China has compared to the MSCI World index itself since Trump was elected:

The biggest decline came with the first threats of tariffs last year; that was followed in time by a rebound after the Buenos Aires "truce" between Trump and China's Xi Jinping last November, while the recent sharp fall dates from the presidential tweets promising extra tariffs on Chinese goods. The Mexican sideshow seems to have distracted the world's attention for a week, but hasn't relieved the pressure on China's biggest suppliers. And there is plenty of downside for them to fall from here.

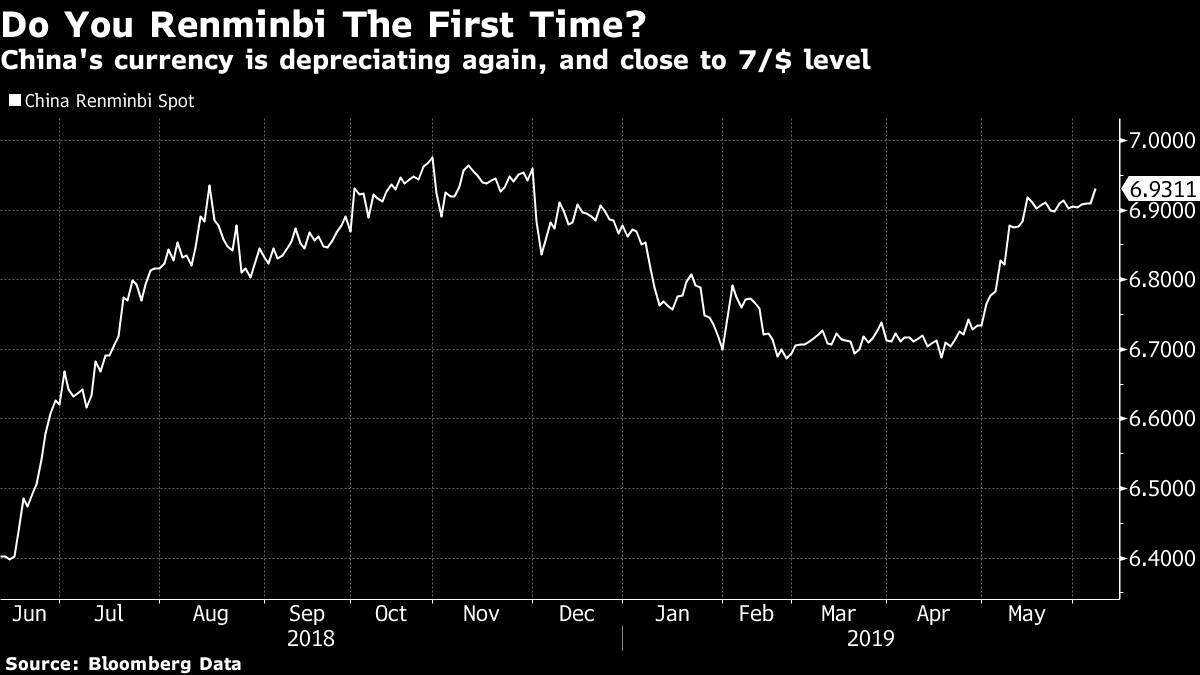

Next, let's take a look at China's currency. A weaker dollar, as we saw last week, makes it easier for the Chinese authorities to keep the value of the yuan below 7 to the U.S. dollar. They would prefer to avoid the provocation that a devaluation would entail. But Monday brought the sharpest devaluation in China's currency in a while:

This isn't a situation that a brief diversion down Mexico way will defuse. It is a subject we will all need to learn much more about. And for this reason, I recommend reading this month's selection of the Authers' Notes Bloomberg book club. "Red Flags" by Geroge Magnus homes in on the way that the arrival of Xi Jinping changed China's economic and political trajectory, and may require other countries to change the way they deal with the world's new economic power. It is fascinating. More on this anon. Unlike a World War II bomber on the moon, there is no risk of the issue of China vanishing any time soon. In search of value. For value investors, times have almost never been more trying. Could that be good news for them?

The following chart shows the performance of the MSCI World Value index (including the stocks that show up as the cheapest on standard screens) relative to the MSCI World Growth index (which includes the developed market stocks showing the most positive growth momentum). The chart goes back 20 years, and it reveals that value investors haven't felt as silly as this since March 2000. That was the month when the tech bubble finally burst, and value investors with boringly cheap stocks were suddenly about to look very clever:

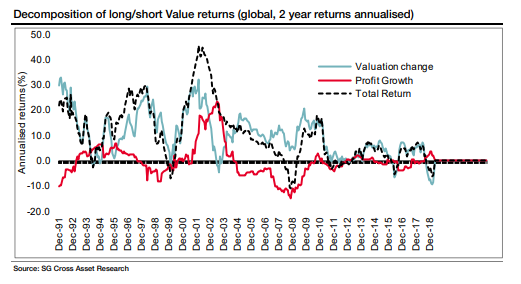

But this isn't quite like the last time. Back then, there was a historic speculative frenzy, which value investors were obligated to sit out. That made them look bad, until the bubble burst – but the value stocks they held, in absolute terms, performed well enough. This time, the following breakdown of returns by Andrew Lapthorne, head of equity quantitative research at Societe Generale, reveals a nagging problem: namely, that value stocks, although cheap to begin with, keep getting cheaper at a historic rate:  Note that profit growth for value stocks has been fine, in absolute terms. This isn't a story of investors piling into "value traps" that turn out to be cheap for a reason. But the long-expected moment when investors realize that the wave of QE-driven buying has left undervalued bargains in its wake hasn't happened, and the bargains are growing even cheaper.

Factor investing is in vogue, along with attempts to work out how to time moves from one factor to another. If you should buy a factor when it is available relatively cheaply, this does look like a time to buy value stocks. But valuation in its own right isn't a reason to predict a market turnaround. Rather, as in 2000, value investors may have to wait for the rest of the market to implode before they start to look good again.

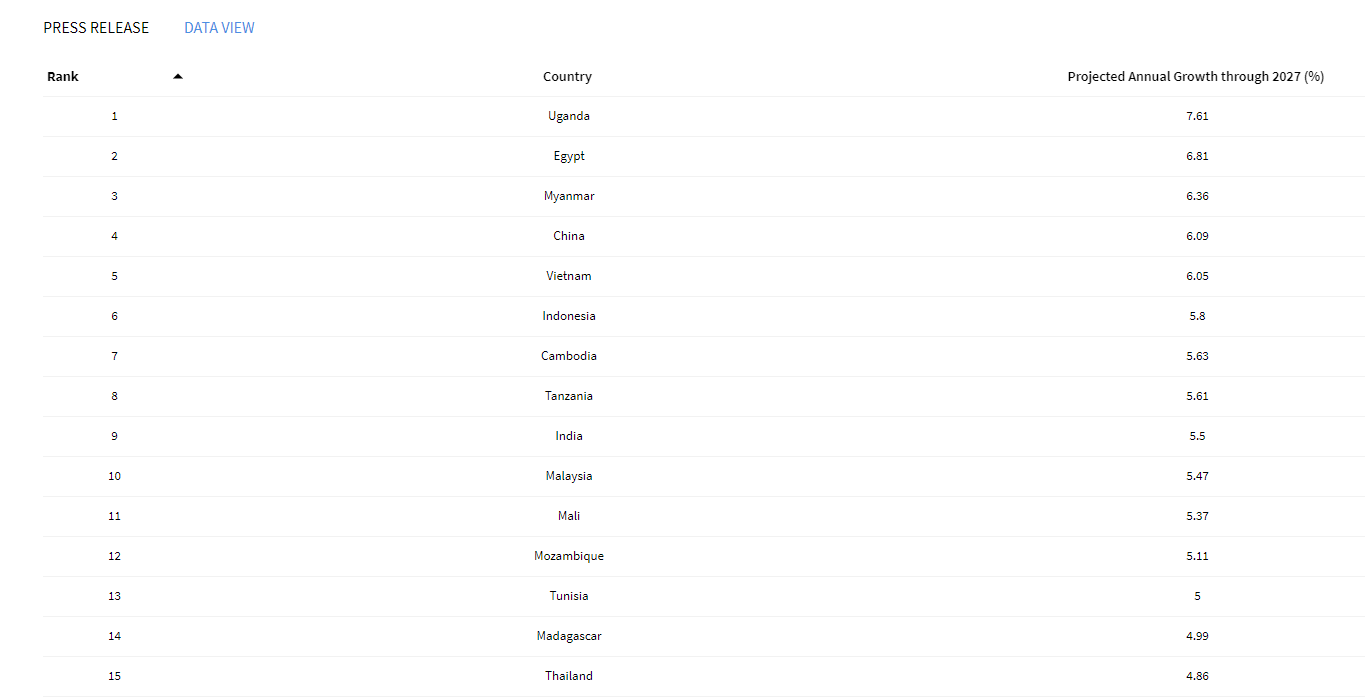

Which countries will manage to notch the fastest growth over the next decade? Nobody can know for certain, but Harvard's Center for International Development has gone to great lengths to try to find out. Its key insight is that growth hinges on economic complexity. The more different skills a population has developed, and the more adaptable its economy, the better its chances of expansion. The more dependent it remains on one industry, the harder it is to achieve growth. It measures this phenomenon in a fascinating and public piece of economic research, known as the Atlas of Economic Complexity. I would recommend anyone with an interest in economic growth to take a look at it. Meanwhile, the center has just published its latest update to its projections, taking into account 2017 trade data. These are the 15 countries it expects to enjoy the fastest growth from now until 2027:  Taking advantage of these insights promises to be difficult for anyone who hopes to restrict themselves to public markets. None of these countries is regarded as "developed," most aren't even classified as "emerging" markets (although the presence of India and China in the top 10 is encouraging), and many don't even qualify as "frontier" markets.

The only stock index I could find for Uganda on the terminal hasn't been going long enough to have any meaning. Solactive does have a Myanmar index that has been going since 2012, however. Sadly, it has underperformed the MSCI All-World index in that time, but here is how it has done:

As for Egypt, a fully fledged frontier market, it enjoyed a resurgence in 2016. According to MSCI, it has slightly outpaced world markets over the last decade:  There are opportunities in the world, but the markets that direct capital to where it can be best used aren't currently fitted to send money to those countries that are poised for the greatest growth. A big splurge of money into any of these markets would only cause problems, as there would in all likelihood be far more funding than could possibly be employed. But anyone with a genuinely long-term focus should probably start looking for ways, most plausibly through private equity or infrastructure, to invest in some of the markets that are poised for greatest growth. Just be careful out there. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment