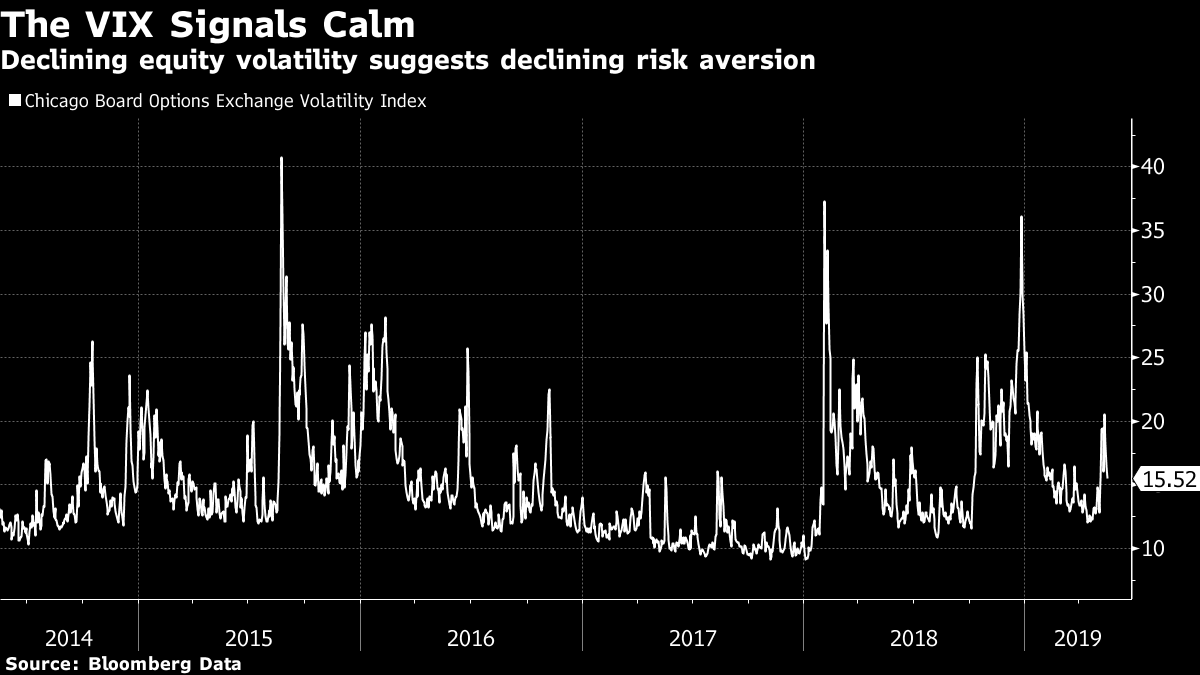

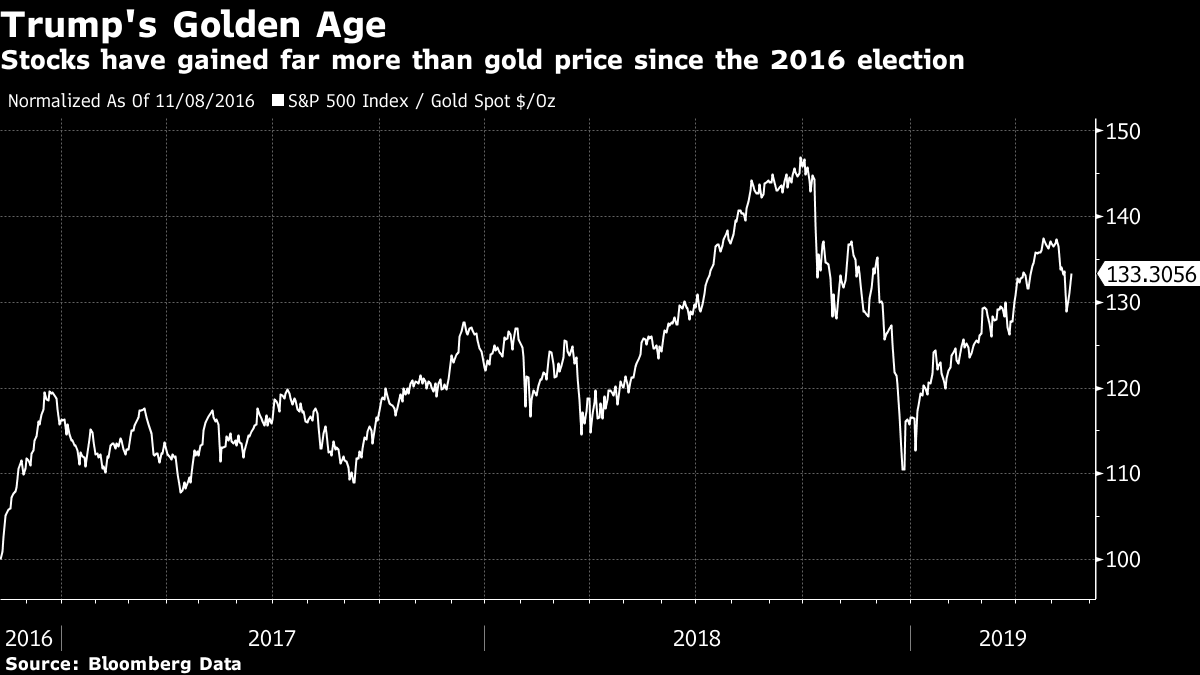

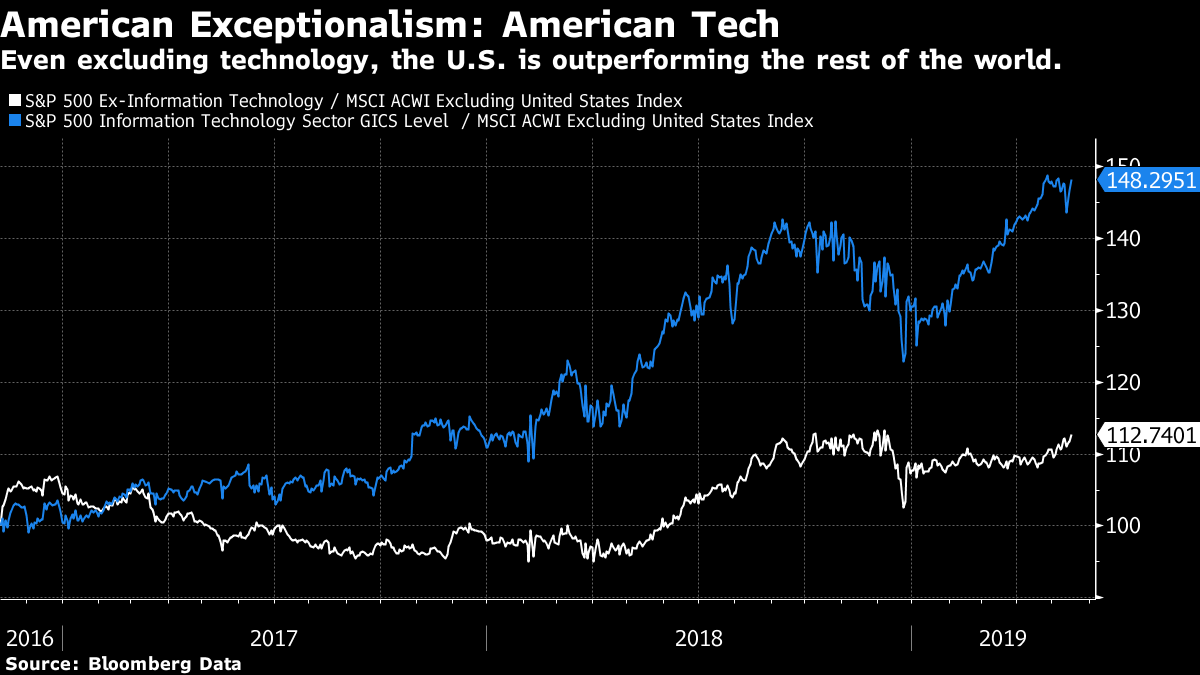

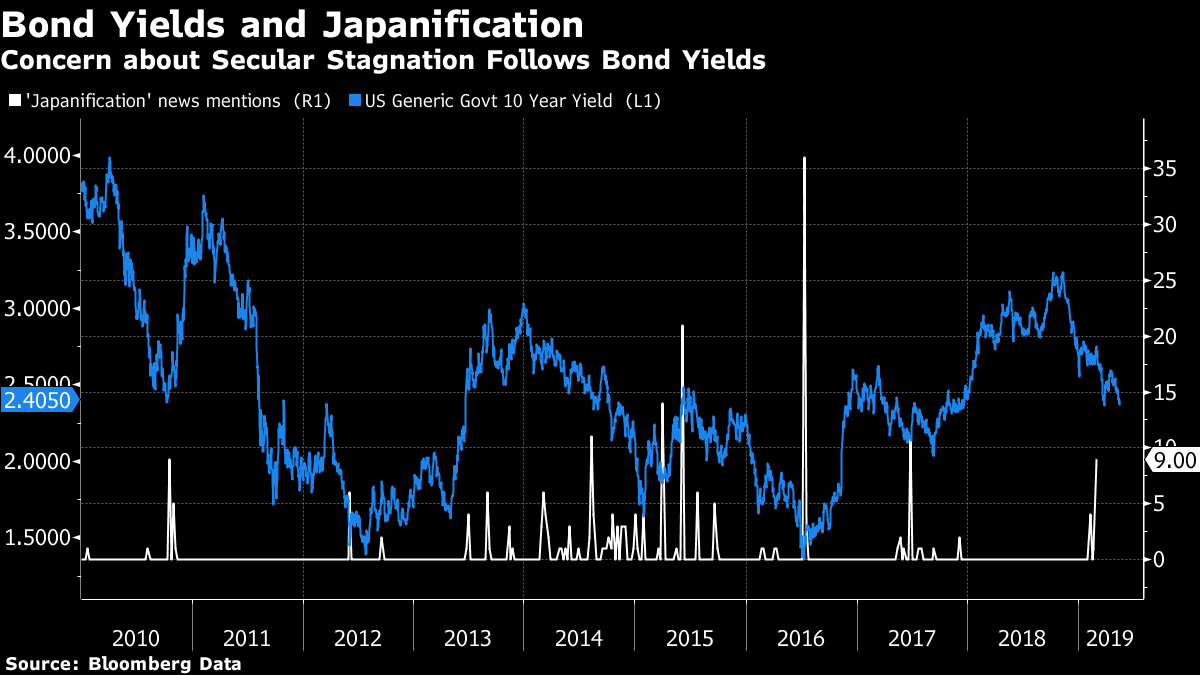

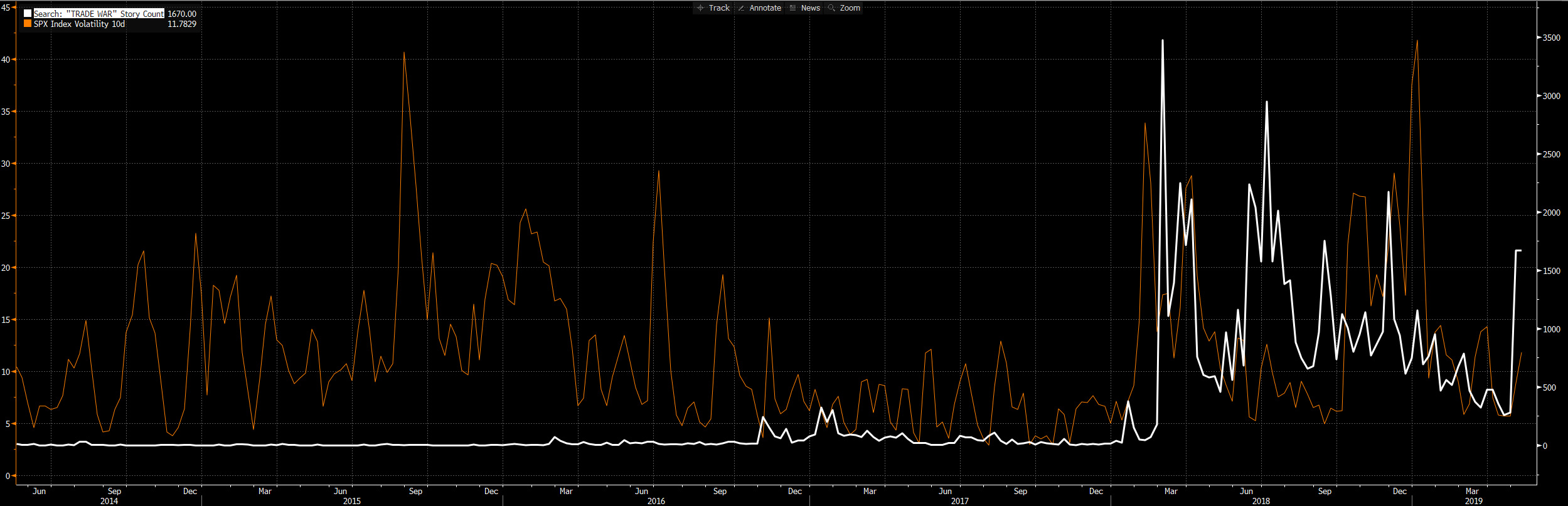

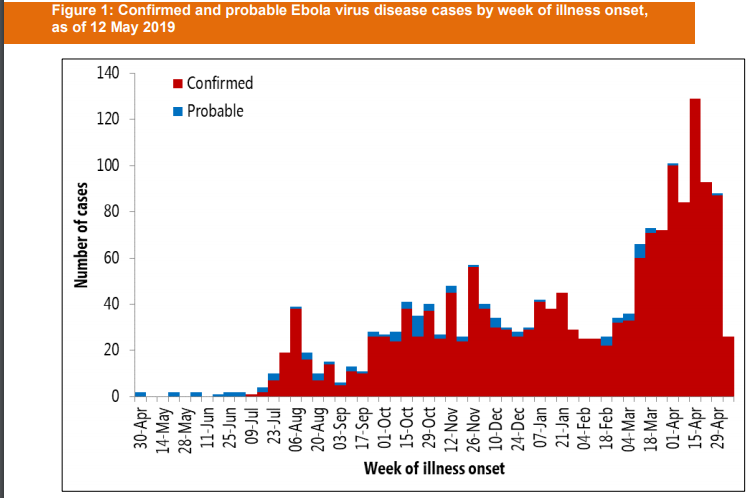

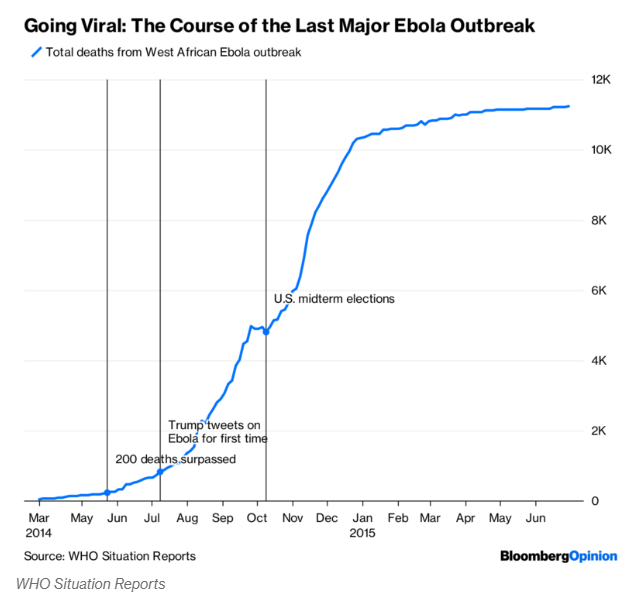

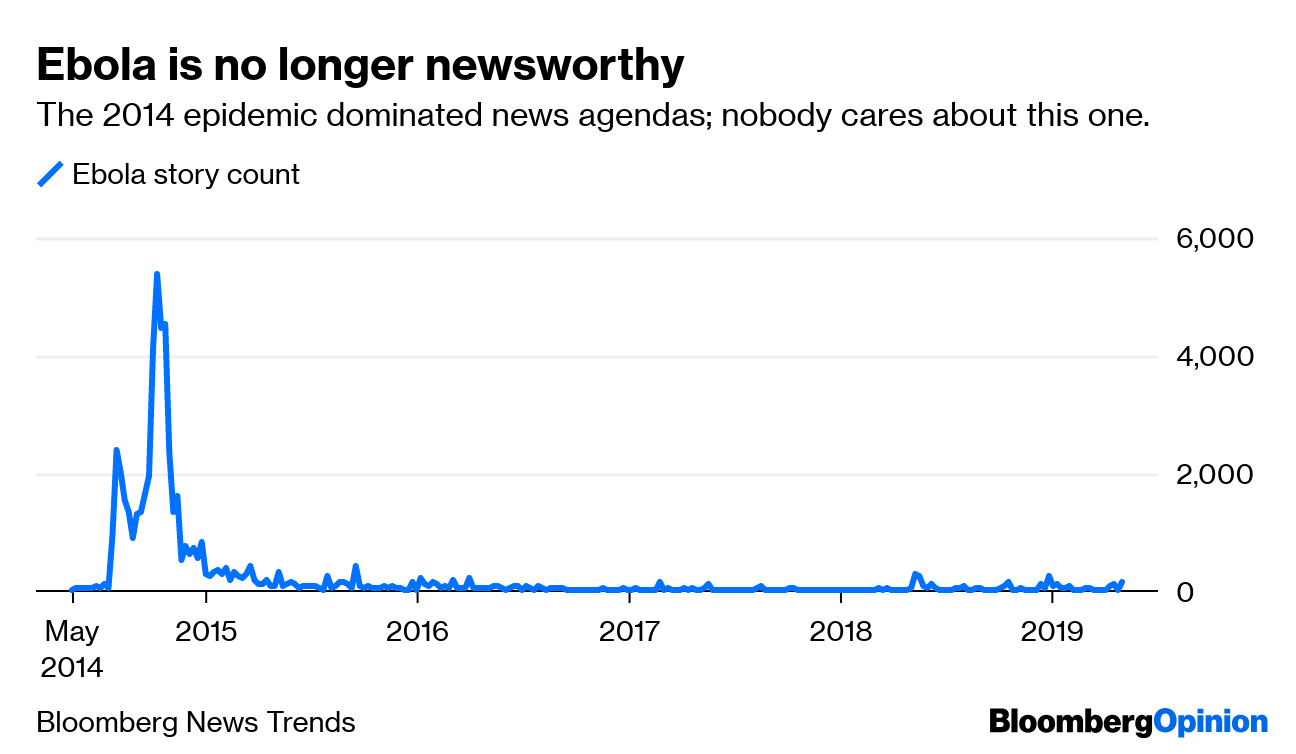

Irrational equanimity. Let us take a sentimental journey through the Bloomberg terminal. Many of us have spent much time analyzing what steps the U.S. and Chinese governments might take next in their trade spat. It's all speculation, as we do not know how it will end. But it is possible to analyze how markets have reacted and gauge the sentiment at work among investors. And they appear remarkably relaxed. This week has seen the actual imposition of 25 percent tariffs on a range of Chinese goods, China's retaliation, and a series of practical preparations for possible war with Iran. None of this would have been predicted even two weeks, and all of this is bad for the markets and the economy. And yet the reaction has been calm, at least in the U.S. and in the stock market. The foreign-exchange market, however, does show concern. The exchange rate between the Australian dollar and the Japanese yen, the old "Yen Carry Trade" in which people borrowed in yen and parked the proceeds in Australian assets to take advantage of the higher interest rates there, has always been a gauge of risk sentiment. When people are nervous, they buy the yen, and when they are confident they buy the Aussie. On this measure, the currency market looks very nervous, although still not quite as alarmed in the days after the U.K.'s Brexit referendum in June 2016.  But another popular measure of risk appetite, the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, or VIX, has stayed relatively calm throughout the drama of the last two weeks:  In the last five years, the event that scared the U.S. market the most, by a wide margin, was the surprise Chinese yuan devaluation in 2015. This round of Chinese trade tension, already abating, is seen as far less alarming. Note that both the Brexit referendum and the U.S. election of 2016, widely denounced as shocking, were also greeted relatively calmly. Looking within the U.S. stock market, there is no great sign that trade fears are prompting investors to move. The following chart shows an index of S&P 500 stocks most dependent on foreign revenues relative to those most dependent on domestic revenues since the 2016 election. There was an immediate grab after the election for the safety domestic-focused companies, but since then exporters have ruled the roost. Yes, exporters sold off more last week, but this is only a slight correction to what continues to be strong relative performance.  Looking for strategies that are working also gives little sense that there is great fear among investors. The following chart shows the S&P 500 Minimum Volatility Index. Minimum volatility strategies buy relatively calm low-volatility stocks, which tend to outperform during times of stress. This has been a very popular strategy among exchange-traded fund salesmen in recent years, but it has not performed well of late:  The Lehman bankruptcy and the Brexit referendum saw big spikes for Minimum Volatility stocks. The gains for those stocks over the last few days have been tiny by comparison. Or, of course, we can look at the classic gauge of risk: the price of gold. Dividing the S&P 500 by the price of gold, to get an effective price of the S&P 500 in gold terms, often belies apparently strong stock market performance. But again, this latest sell-off looks tame when valued in gold. Valued this way, stocks are still well under President Donald Trump, even if they remain below the high they made last fall before worries about a hawkish Federal Reserve set in:  The trade war is primarily a bilateral affair, which stands to push up prices for consumers and damage the prospects for exporters in the U.S. and China. But the trade spat has barely dented the continuing outperformance by the U.S. compared to the rest of the world since 2016. Much of this is to do with Silicon Valley and American dominance of the tech sector. As the chart confirms, the S&P 500 tech sector has massively outperformed MSCI's index of all the world's stock markets outside the U.S. since the election, and this has only sustained a slight dent in the last few days. Meanwhile, the rest of the S&P 500, compared to the rest of the world, has been far less impressive, but has had no correction at all during the trade conflagration:  There is another market that can be taken as a gauge of confidence of the economy: bonds. Falling bond yields often indicate declining confidence in the economy. Bond yields in the U.S. are close to their lowest since 2016. In Germany, the yield on 10-year bunds has again gone negative. This does appear to suggest major concerns and a flight to safety. But if we look at other indicators of mood and of investor preoccupations, this drop in bond yields looks different from the one that came before. In the following chart, the white line shows incidences of the word "Japanification" week by week in Bloomberg's news trends function. (The function is NT } for those with a terminal.) The decline in bond yields in the summer of 2016 after the Brexit referendum was accompanied by huge concerns about Japanification. The risk of Japan-style stagnation appears greater now, at least for the euro zone, but this run on the bond market has not been accompanied by similar speculation that Europe or the U.S. will be Japanified. This time, apparently, lower bond yields appear to be perceived more as a good thing rather than as an intimation of disaster:  As for trade itself, I tried mapping incidences of the phrase "trade war" against volatility in the S&P 500 over the last five years. The result is messy, thanks to my incompetence with the graphic function, but looks like this:  The white line shows incidences of "trade war" in news pieces, and we see that the possibility was never taken seriously until early last year. And for some reason, all of last week's hectic activity has left this count far lower than it was when the Trump administration started to pump up the rhetoric more than a year ago. The Christmas Eve sell-off in markets came despite a relaxing in trade tensions as gauged by news mentions. The peak in mentions of trade wars in the spring of 2018 came as the S&P 500 was steadily gaining. Put all of this together, and the only conclusion is that U.S. investors are remarkably relaxed about the situation – probably too relaxed. As my former Financial Times colleague Michael Mackenzie puts it, this is not even half a healthy correction. I asked Peter Atwater, author of the book "Moods and Markets," for his take, and he suggests that the problem is psychological distance. Issues like trade tariffs are not immediately present to us, and can thus safely be ignored. Many of the risks involve a large probability that we will be OK, coupled with a smaller probability of something existentially disastrous. To quote Atwater: And there you have it. Assuming the many existential risks that are out there can and do remain psychologically distant, there is no reason the markets can't and won't melt up from here. Investor complacency is staggering. Forget Beyond Meat; we are now beyond words. This risk, however, is existential. If one of the risks identified above becomes real, it will be game over. When it comes to investors' binary decision-making, it will be all or nothing. This is a market without a net. Back through Monday's low a cascade could easily take hold. In the meantime, party on. This is a fair assessment. And finally, just in case you did not click on the first link, rest in peace Doris Day. Ebola: not going viral. I have one more example of irrational equanimity to offer. The current outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo is appalling. These are the latest numbers, as reported by the World Health Organization:  For reference, there are more than 1,100 probable deaths so far. Let us compare that with the course of the highly publicized epidemic that broke out in west Africa in 2014. By the time this many deaths had been recorded on that occasion, Trump, then a private citizen, was already tweeting about the dangers to the U.S., and the issue had become a political issue in that year's mid-term elections. And the epidemic would get far worse before there was any improvement:  But the outbreak in the DRC is still getting minimal news coverage. The contrast with the 2014 outbreak is stark, and unsettling:  It might help the suffering population of the DRC if Trump were to start tweeting about their misfortune as avidly as he tweeted about the outbreak in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. Markets might prefer it if he didn't: the Ebola scare of 2014 was a disgraceful episode in many ways, and was accompanied by a dip in the markets. This new outbreak is causing no damage to the world's developed economies. But the risks that it could do so are real and growing, just as they were at the same stage in the 2014 outbreak. Five years ago, the markets seemed irrationally scared about it. This time around, they look irrationally calm. Dear Chairman. A reminder that this month's book in the Authers' Notes book club is "Dear Chairman" by Jeff Gramm, a brilliant history of shareholder activism. There is an IB chat room on the Bloomberg terminal where I will try tomorrow to oversee a discussion of the first three chapters (including the activist exploits of the young Warren Buffett and Benjamin Graham). Email us at authersnotes@bloomberg.net and we can give you access to the chat.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment