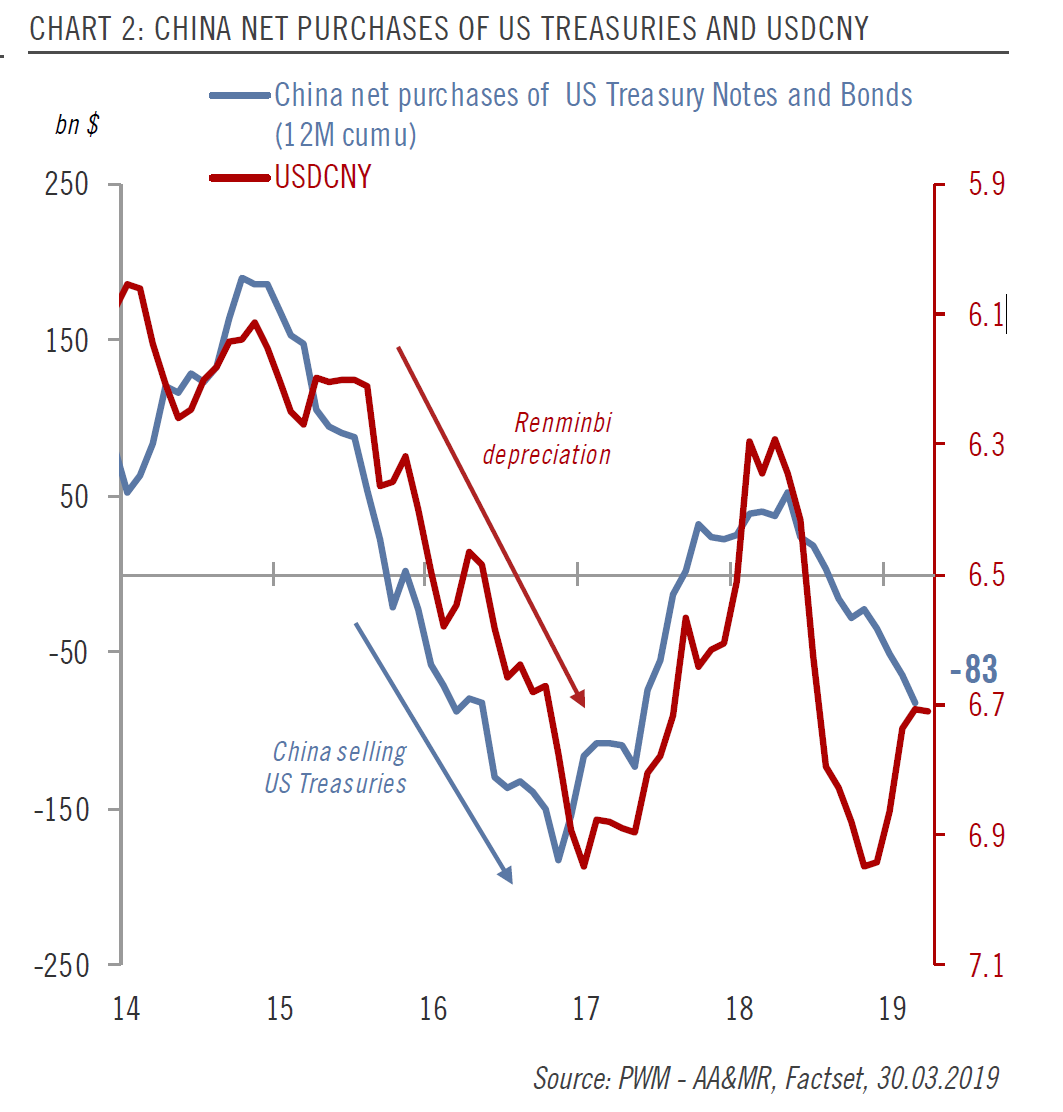

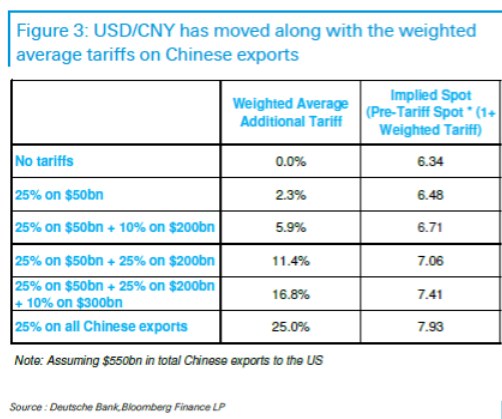

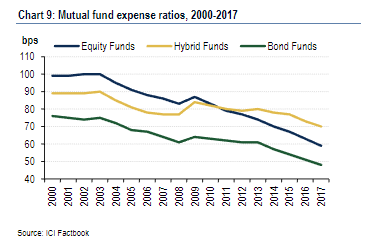

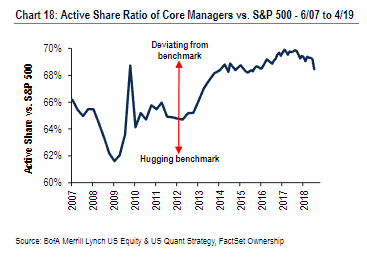

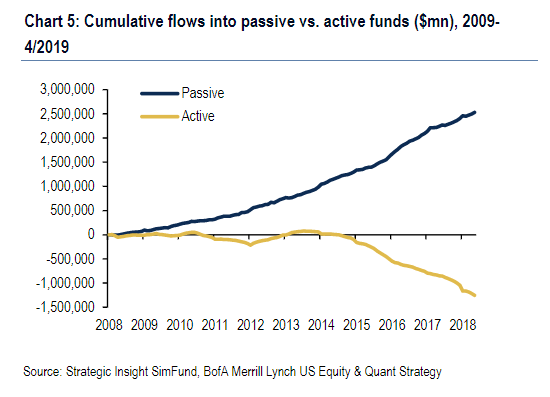

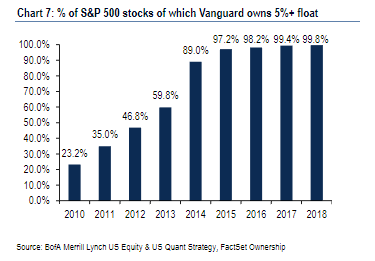

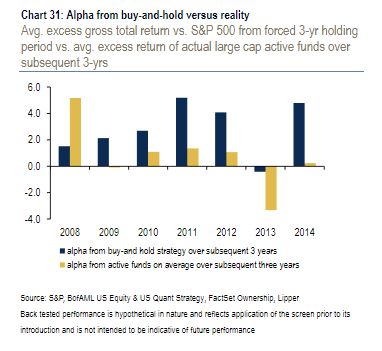

Seven is a lucky number. Round numbers tend to matter in markets. So it is that the foreign-exchange community is dominated by one question, which is whether China's yuan will breach the seven-per-U.S.-dollar level. The question is freighted with history. The currency steadily appreciated after July 2005, when the Chinese authorities ended the currency's peg of 8.3 to the dollar that had endured since 1995. It finally strengthened below seven per dollar in 2008 and has stayed there ever since, meaning the yuan has remained relatively strong. It now looks as though that could be about to change:  The yuan has an anomalous status. It is no longer a pure expression of the wishes of Chinese authorities, but it is still not a pure expression of the will of the market either. A move above seven would have once been taken as an act of aggression by the Chinese authorities. Now there is also the possibility that it could be taken as a loss of confidence in China or economic weakness. Either way, it would matter. A depreciation beyond seven would be a significant counterweight to the tariffs on Chinese goods now being imposed by the United States. Simon Derrick, head of foreign-exchange for Bank of New York Mellon in London, offers this summary of why it matters: How important is CNY 7.00? Beijing has a history since the summer of 1998 of stepping in to minimize currency market volatility when there is a concern it could feed through into broader asset market turbulence. Given the authorities held the line at CNY 7.00 in Q4 of last year (the USD hasn't traded above there since 2008) it seems reasonable to assume they are concerned that a rapid move beyond this level might lead to heightened volatility in a range of markets and that this is worth defending against. Set against this is the fact that China's FX reserves have been maintained in a range between USD 3 Trn and USD 3.2 Trn for around 3 years now. While this is not the only tool in Beijing's armoury for defending the CNY, as the use of tighter funding costs and higher than expected fixings last year highlighted, it remains the most significant. Therefore the unanswered question is how important the authorities consider holding the value of the reserves at around the USD 3 Trn level? So letting it move beyond seven could be a sign of weakness (and dwindling currency reserves) rather than Chinese aggression. Pictet Asset Management points out that China's central bank has handled its huge reserves of U.S. Treasuries like any central bank that is trying to defend a pegged exchange rate. In other words, when its currency weakens, it sells Treasuries, thereby strengthening its own currency. The pattern over the last five years is the exact opposite of what might be expected if China wanted to use its Treasuries as a weapon, and also suggests that it wants to stop its currency from declining too much:  Luca Paolini and his team of strategists at Pictet argue that China has a strong need to defend the seven per dollar level. He also points out that the fundamentals are making this harder. With China cutting interest rates to stave off a slowdown while the Federal Reserve has tightened its monetary policy, the spread between rates in the two countries has narrowed sharply. This makes it harder for China to keep its currency from depreciating:  As Paolini says: A stable currency would make China better able to attract long-term foreign investors and fund its future growth. This long-term objective should prevail as long as China doesn't feel a fatal threat from the external world. The current context is tense indeed but not to that point… Trade tensions between the US and China have risen sharply but we believe the situation would need to escalate much further before China resorts to the extreme weapons of currency devaluation and/or selling down its US Treasuries. The fundamental reason for this argument is that such strategies do not serve China's own interests. On the contrary, they could cause severe damage to the Chinese economy. Should markets amplify that fear and price-in some of that worst-case scenario, it would probably coincide with an extremely weak context in local Asian currencies against the US dollar. With China needing a stable currency, as well as good relationships with the rest of the world, to maintain its growth, any attempt to devalue its currency could be as disastrous for China as for everyone else. Meanwhile, selling Treasuries would push up rates in the U.S., and thereby in all probability prompt an exodus of funds from the emerging world. That would be a disaster for China's economic interests. That said, the Chinese may not be inclined to fight as hard as they might have once done. The tariffs imposed by the U.S. create pressure for depreciation as the foreign-exchange market attempts to counteract them. This table from Deutsche Bank foreign-exchange strategist George Saravelos suggests that the latest escalation, once it comes into full effect, should be enough to push China's currency through the seven-per-dollar level:  Saravelos argues that the Chinese authorities may be prepared to let their currency pass through the landmark this time. In the teeth of extra tariffs, they may have little choice. He says: Based on our recent trip to Beijing, we feel policymakers will be more agreeable to CNY depreciation now. First, Chinese policymakers appear more prepared for trade frictions and proactive in managing the growth fallout; growth is in better shape than last year, and the economy has responded to earlier stimulus. In 2018, when domestic data was poorer and there were fears of growth falling below 6.0%, a break above 7.00 was less acceptable, given risks of a negative feedback loop to an already weak economy. With the trade war likely to be protracted, finding ways of keeping domestic growth supported should be a priority for policymakers. This is likely to require looser monetary policy, which could come at the cost of a weaker currency. Authorities should be more willing to bear that cost this time. Second, concerns over the "externalities" to currency weakness — hot money outflows and corporate stress seem more limited this time. Regulators appear more confident that years of regulatory measures will keep hot money outflows manageable. Corporates are now better hedged against FX weakness, and industrial profitability has been stronger, reducing concerns about the corporate balance sheet impact from a weaker CNY. Importantly, we have noted that CNY has been reacting predictably to the imposition of tariffs over the past year, with the move higher in USD/CNY proportional to the weighted average tariff being borne by Chinese exports to the US. The latest increase in tariffs to 25% on $200bn of goods is consistent with USD/CNY close to 7.10. If Trump proceeds with tariffs on $300bn, even at an initial 10% rate, this could take USD/CNY to 7.40. All this said, recent history suggests China will still want to keep the currency below the round number of seven per dollar if possible. Given the difficulties stacked against it, how can it do this? Mellon's Derrick suggests two alternatives. One is the "line in the sand" approach, at seven per dollar. The problem with this can be seen from previous desperate episodes in the history of the Bank of Japan. In 2003, the BoJ sold $38 billion in an attempt to keep the yen at 115 per dollar, but gave up after two weeks. Derrick notes that "the market became used to the presence of the BoJ," and so the impact of their actions became increasingly muted "with investors ultimately just using the intervention as an opportunity to buy cheap" yen. To this, we might add that selling that many reserves would also run the risk of pushing up U.S. rates, which would be dangerous. An alternative strategy is the "bear trap." In 1994, Derrick points out, the BoJ had failed to stop its currency moving from 100 per dollar to 96, the weakest level ever for the dollar at the time. To counteract a huge bearish interest in the dollar, it then bought more than $1 billion of the U.S. currency on one day, more than 10 times the amount it had bought the previous day, in a successful attempt to force the dollar up and inflict enough losses on the bears to scare them away for a while. The People's Bank of China has a recent history of catching investors off guard even when it did not mean to, as in its badly botched devaluation in the summer of 2015. A deliberate bear trap is a startling possibility, but easy to imagine. And at least it would show that China wanted to keep its currency reasonably strong. The alternative, that it no longer has the means or the will to do so, would be more worrying. The trade war and the tech war understandably garner more attention, but this currency war could also make a huge shift in the international terms of trade. Actively responding to passive aggression. The rise of passive index funds has been one of the salient features of the post-crisis financial markets. It puts traditionally managed active funds into an almost hopeless position, and not just because index funds are cheaper. With most stock market money now in institutional hands, trying to beat the market is more of a zero-sum game than ever. And as active managers leave the field, that zero-sum game is being played by ever more talented individuals, making it harder to win. For a counsel of despair for passive managers, try the excellent "The Index Revolution" by Charley Ellis. But perhaps what is most depressing for active managers is that they are doing everything that needs to be done to combat the rise of passive — and it is not helping. That was my main take-away from a report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch's quant unit on active management. It makes clear that the rise of passive funds has indeed triggered a big response from active funds. Most importantly, active funds have reduced their fees drastically, across all asset classes:  This is exactly what logic suggests they should do. The less passive funds undercut them on fees, the better the argument for seeing if an active fund can actually beat the indexes. Active funds also seem to have taken on board the message that there is no point being active and then hugging an index. Cheaper, straight index funds are a better bet than a "closet index" fund. But growing ever more active, taking concentrated positions or holding little-known stocks that are not in the main indexes provides a valid alternative to an index fund. Such an active approach has a much better chance of beating an index by a wide margin. Highly influential research first published by Antti Petajisto and Martijn Cremers in 2006 introduced the notion of "active share" (the higher proportion of a fund's portfolio that deviated from its benchmark, the higher its active share), and found that funds with higher active share tended to log better performance. Many institutions now require a high active share when looking for active managers to manage mandates. The Bank of America Merrill Lynch report shows that active share has indeed risen in the industry post crisis, although the attempt to grow more active has petered out a bit in the last two years:  The recent drop in active share may be due to the growing popularity of factor investing, which involves disciplined investing in a benchmark index, but with a tilt towards those stocks that are better value, or have a higher yield, or stronger growth, and so on. Such funds generally show up as having a low active share, but they can still justify a claim for your money if they couple that with low fees. So the active industry is doing the right thing. And it is not helping. There are growing worries about the extent of the influence of the biggest indexing groups, but there is no sign as yet that this is deterring people from buying their products. The trend for money to flow out of active funds and into passive continues unabated:  Bank of America Merrill Lynch offered one extraordinary illustration of the possible downside of passive dominance. Vanguard, which pioneered index funds, is now a prominent shareholder in virtually every company in the U.S. As this chart shows, it now has at least 5 percent of the free float of shares in 99.8 percent of the companies in the S&P 500 Index. This turns it into potentially a hugely important economic actor:  It is small wonder, then, that the corporate governance approach taken by Vanguard and the other big indexers is now such a matter of concern and debate. They cannot sell their shares, so the way they choose to vote their shares and use their influence thus becomes of paramount importance. Vanguard recently released new guidelines for its corporate governance, which can be found here and here. What more can active funds do to stop the rise of passive funds? A small industry has developed over the last few years attempting to answer this question. One of the most interesting suggestions I have seen comes from Bank of America's Savita Subramanian. They should simply do what all the literature says they should do, and resist the temptation to trade too much. In the following chart, the blue bars show what would have happened over the subsequent three years if funds had held their portfolios unchanged for three years. The yellow lines show what actually happened.  Beyond cutting costs and concentrating their portfolios, maybe the next lesson active managers have to take on board is to have the courage of their convictions. With some patience and lower trading costs, they might be able to put up a better fight. Caudillo-watch. As a political shock emanates from Australia, India seems likely to stick with Narendra Modi, and the world braces for populist triumph in this week's elections for the European parliament, Latin America provides some evidence that we should all calm down about politics. In the last 12 months, both Mexico and Brazil have elected new presidents. Both have now had a few months in office. First, Mexico elected a left-wing populist, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who proceeded to scare international investors before calming down a little in office. Then Brazil elected Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist, amid speculation in world markets that he was finally the person to deal with the country's underfunded pension system, which has put a severe strain on its finances. Now, it looks as though he has little more chance of dealing with the issue than his predecessors.

So it has been an exciting time, with the region's two biggest countries going in opposite directions. Now let us see the relative performance of the main benchmarks of Brazilian and Mexican stocks over the last 12 months:

Not only is the performance of the two countries almost identical. They are both back exactly where they were 12 months ago. Take note of this week's elections. It would be foolish not to. But the Latino lesson is that we should still stay calm about it.  Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment