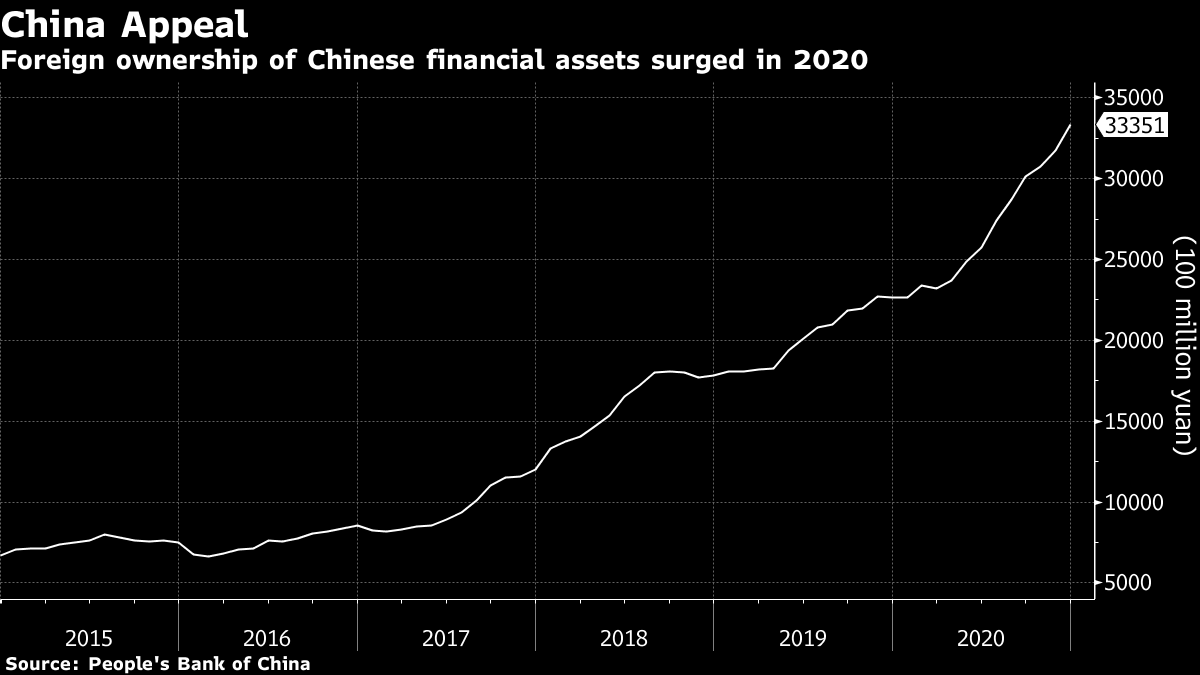

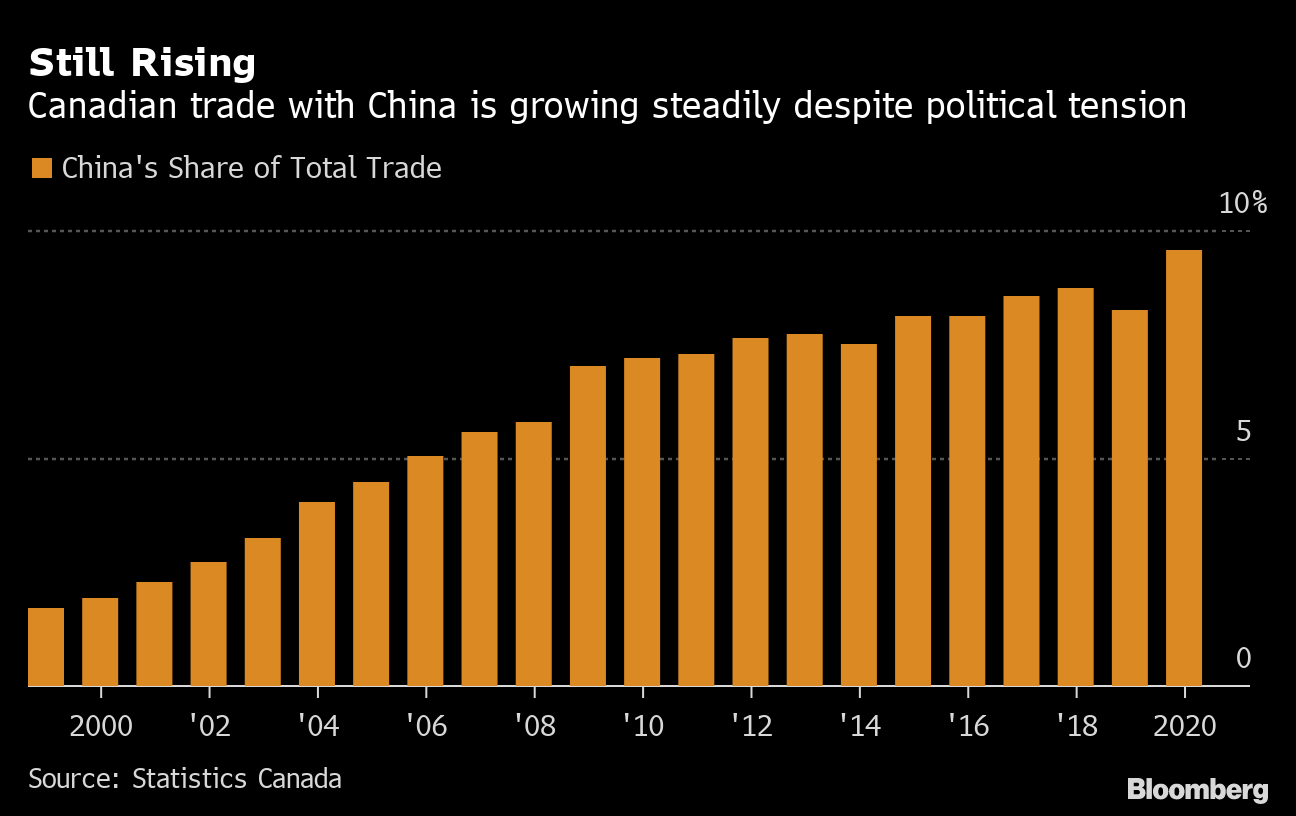

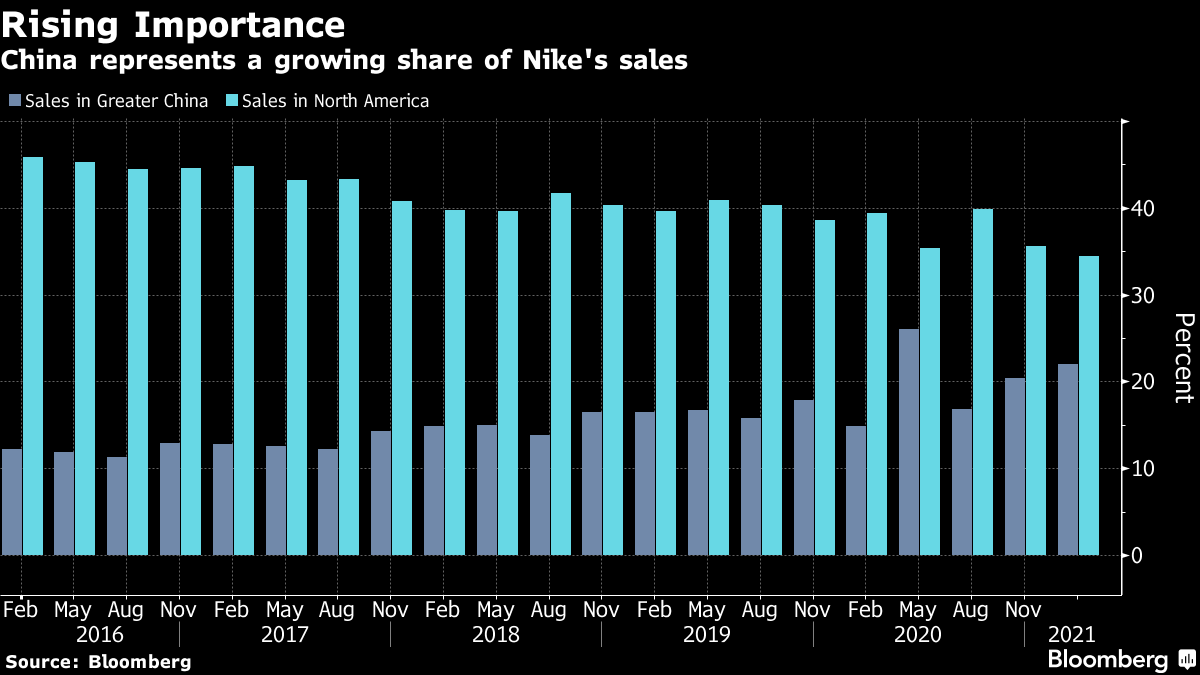

| China's financial regulators are obsessed with risk and one of their more-notable bugbears as of late has been America. The example from this past week has been hot money. The term refers to capital that rushes across borders in the hopes of making a quick profit. When the amounts are large enough, such flows can be very disruptive, which explains why Yi Huiman, China's top securities regulator, has begun calling for strict controls on hot money. But why now? In explaining the concern, Li Daokui, a former member of the Chinese central bank's monetary policy committee, pointed to the U.S.'s $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package. Washington's stimulus is boosting the outlook for American growth and inflation. That in turn is pushing up bond yields and prompting investors to sell risker assets. The implication is that in the second half, China could see large outflows of hot money. There's reason for Beijing to worry. China has seen substantial inflows as its economy bounced back from the coronavirus more quickly than any other major market. Foreign investors, for example, bought 570 billion yuan of Chinese government bonds last year, more than double the amount purchased in 2019. A sudden reversal in that trend could be a source of substantial volatility.  Of course, U.S. stimulus measures also benefit China by fueling demand for the country's exports, though that hasn't stopped the concern. Li, who's currently director of the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practices and Thinking at Tsinghua University, ranks hot money among the two biggest risks for China's economy this year, the other being a possible wave of bond defaults. Beijing's objection, to be clear, is not with Washington taking steps to shore up its economy. That's something any responsible government would do. What irks Chinese policy makers is America's dominance of the global financial system and what Beijing sees as a lack of U.S. regard for the outsized impact its actions have on the world. Indeed in August of last year, China's top banking regulator railed against U.S. stimulus measures for that very reason. Guo Shuqing, who is also the Communist Party Secretary for the central bank, wrote in an article for Qiushi magazine that "unprecedented, unlimited quantitative easing" by the Federal Reserve was eroding global financial stability and could be pushing the world toward another crisis. Risk emanating from the U.S. was a subject Guo broached again earlier this month. Speaking to reporters on March 2, he said he was "very worried" about bubbles building up in American and European financial markets and what the implication would be for China if they burst. But perhaps these protests should be expected. After all, with the rise of China's power and influence, its leaders have bristled at American preeminence in fields from technology to diplomacy to trade. There's nothing that makes finance any different. Alliance BuildingThere's much that remains unclear about how U.S. policy toward China will evolve under President Joe Biden. What his administration has made clear, however, is that it intends to work far more closely with allies on pressuring China than did the Trump administration. The first action produced by that strategy emerged this week when the U.S., EU, U.K. and Canada in coordination imposed sanctions against China over actions Beijing has undertaken in Xinjiang. China lashed back by imposing sanctions of its own. This exchange highlighted the risk of escalation and the precarious position many of America's allies now find themselves in. Take Canada for example: Two of its citizens were detained in China after Huawei's chief financial officer was arrested in Vancouver in response to a U.S. extradition request. That plunged bilateral ties into crisis, even as trade with China becomes ever more significant for Canada.  U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken acknowledged that conundrum this week when he said in Brussels that Washington won't force allies to make an "us-or-them choice" between America and China. While many nations will be glad to hear that sentiment, turning words into action will doubtless be more challenging. Xinjiang CottonWhen politics and business clash, the results are seldom pleasant. That was the case this week for Nike, H&M and a slew of other brands embroiled in a maelstrom over cotton grown in Xinjiang, the westernmost Chinese province where Beijing has been accused of human-rights abuses against the Uyghur ethnic group. For those companies involved, it was a conundrum with no good choices. Using cotton from Xinjiang risks not just criticism in the U.S. and Europe, but also sanctions. Stopping, however, threatens to spark consumer boycotts in the world's second-largest economy. Those are two bad options, especially for companies like Nike that have seen sales in China surge in recent years.  Regulating DataJack Ma, China's best-known billionaire, has been calling data as valuable a resource as water, electricity and oil since at least 2015. And now Beijing appears to be catching on. It was revealed this week that regulators led by China's central bank have proposed setting up a joint venture with the country's tech giants to oversee the lucrative data those firms collect from hundreds of millions of consumers. While the companies would be shareholders, the venture's top executives would have to have the blessing of regulators. It's not just Beijing that's realizing how valuable data is. Governments around the world are waking up to that fact and grappling with the regulatory implications. China's answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, seems to involve a fair amount of government involvement. IPO SqueezeSince Chinese regulators put a stop to Ant Group's dual IPO in Hong Kong and Shanghai late last year, the scrutiny of companies looking to sell shares publicly in Shanghai and Shenzhen has increased substantially. More than 80 companies have withdrawn applications for share sales so far this year, compared with nine in the first quarter of 2020. The greater care with which regulators are considering applications has also contributed to a growing backlog, which as of this month was more than 730-companies long. This week offered a glimpse of what this new level of scrutiny looks like from an issuer's perspective. Geely Automobile, one of China's best-known carmakers, got approval from Shanghai's stock exchange to list on its Nasdaq-style Star board last September. In the past, it has typically taken less than three months for a company to list after getting the greenlight from the exchange. Geely, however, hit a snag. Its proposed share sale came just as authorities were weighing tightening IPO rules for the Star board, which was created to help innovative technology companies raise capital. That's resulted in regulators examining Geely far more closely, including trying to ascertain if the company is high tech enough for the bourse.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: Something new we think you'd like: We're launching a newsletter about the future of cars, written by Bloomberg reporters around the world. Be one of the first to sign up to get it in your inbox soon. |

Post a Comment