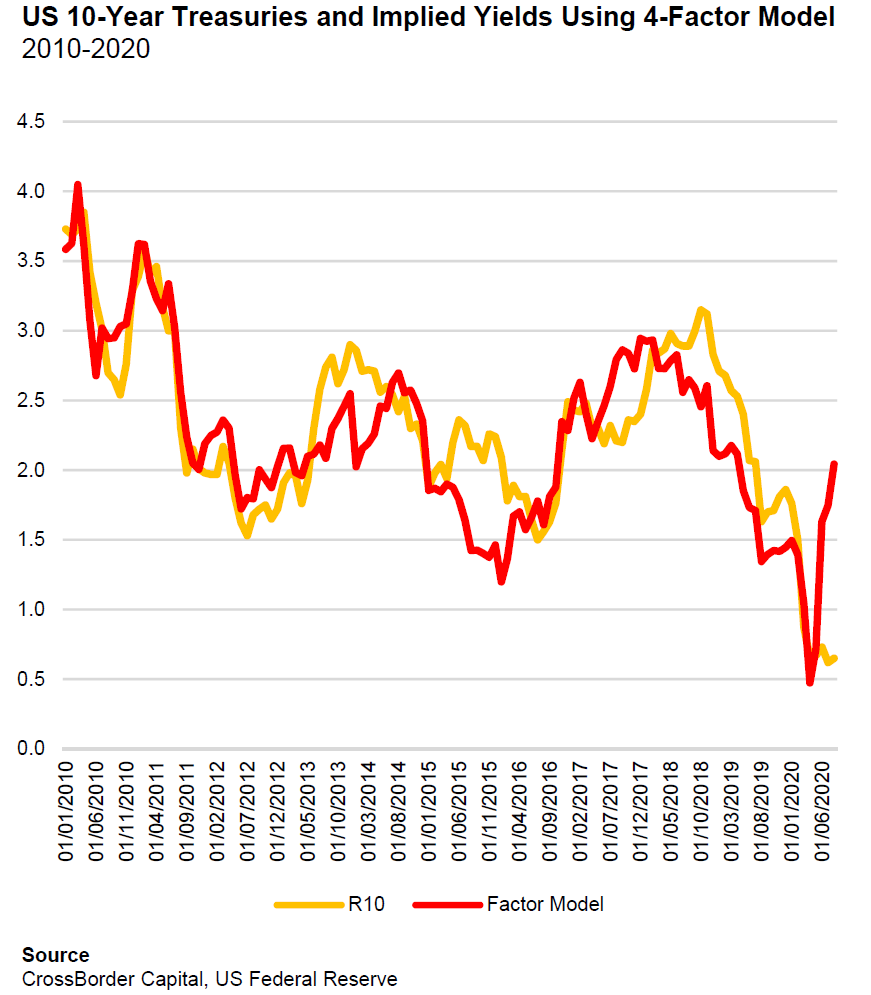

Lend to China?It has been an article of faith for a long time that signals from Chinese markets aren't to be trusted. They are tightly controlled by a government that is increasingly communist in more than name. The two equity bubbles in the last two decades were both driven by incautious governmental manipulation; and the authorities similarly have ultimate control over the debt market. By comparison with the yields on Treasury bonds, which provide the financial baselines for the rest of the world, messages from the Chinese bond market should be treated with more skepticism. Except now, it might just be the other way around. Over the last six months or so, as the Chinese and world economies have staged a recovery from their seizure earlier in 2020, the country's 10-year bond yields have done exactly what might be expected, and risen. They are roughly back where they started the year. Meanwhile 10-year Treasury yields have dropped like a stone, and then stayed in a tight range around 0.65% to 0.7% as if under the jackboot of a veteran communist planner:  How unnatural is the comatose performance of the U.S. Treasury market since March? Mike Howell of Crossborder Capital Ltd. in London built a model to predict 10-year Treasury yields based on four factors that usually correlate closely with them: the amount of U.S. liquidity, U.S. ISM data, the ratio of copper to gold, and the change in the Australian dollar. The predicted course of yields using those factors is shown by the red line below, while the actual performance is in yellow:  To get the kind of rise in yields implied by the model would require a selloff of 10% to 15%. Being in the U.S. market when this happened wouldn't be good. So, many of the objections that usually apply to Chinese investments seem at this point to apply to U.S. Treasuries. Intervention is holding them at an artificial level, and investors effectively need to rely on central bankers and politicians to keep up their support indefinitely, or suffer a capital loss. Before getting too carried away, we need to return to the Chinese reality. The country, we know, has been funding its ascension with debt for a long time. That debt has somehow managed to stay in the complicated tubes and pipes of China's financial system, and a Minsky Moment has been avoided — three years after the outgoing head of the People's Bank of China actually warned in so many words of such a danger. Could it now conceivably make sense to lend money to the Chinese government? Trust to logic, and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that it does. Emerging market debt, very exposed to perceptions of China's economic strength, has enjoyed a great rally of late, after briefly wobbling on the edge of crisis in March:  Luca Paolini, chief strategist of Pictet Asset Management Ltd., told me that he not only liked emerging market equities and debt, but especially Chinese bonds. "They have an unusual combination of very low inflation, and relatively traditional monetary policy, and a wide spread over U.S. Treasuries. And China also benefits from the inclusion in different benchmarks." After years of aggravation over whether the nation should be admitted to the MSCI emerging markets equity index, a development that would open the door to a big new range of both passive and active institutional investors, Chinese bonds found their way into the two main gauges used by global bond fund managers with little fuss. They entered the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate early last year, and last month were added to the FTSE Russell World Government Bond Index. In both cases, China has leapt straight into classification as a developed market, rather than the emerging market status it has in equities. That opens Chinese debt to more institutions and also makes it more likely they will buy more. Within the FTSE Russell index, Chinese 10-year yields of a little above 3% will be second only to Mexico's. That is likely to appeal to investors who are used to shopping for bonds from the U.S., the European Union and Japan, all of which have negligible or even negative yields. And thus Teresa Kong, portfolio manager at Matthews Asia, suggests that index inclusion should attract more than $120 billion in foreign capital into Chinese bonds. Chinese bonds have traditionally had low correlation with the rest of the world, but that is in part because the economy has behaved very differently, while the government has maintained a measure of control over the market that doesn't happen elsewhere. It may not be wise to bank on low correlations in future. Then there is the benefit that in real terms, after accounting for different levels of inflation across countries, China's currency is still somewhat weaker than it was in 2015, before the unexpected and poorly communicated devaluation that briefly flung world markets into crisis. The yuan's level is, of course, very political. It requires some degree of trust in Chinese officialdom. But on the face of it, the currency looks cheap, which is attractive:  Another short-term argument for China comes, inevitably, from the coronavirus. The "China Virus," as it is now known to many Americans, may have originated there, but the country also managed to bring it under control far more effectively than many others. The same is true of neighboring northern Asian nations, notably South Korea and Taiwan. As Paolini of Pictet points out, these countries haven't had to resort to fiscal stimulus on the scale seen in the EU and the U.S., and that makes their equities, as well as their bonds, attractive. These countries jointly make up more than half of the emerging markets equity universe. In the longer term, there are opportunities that can also be viewed as risks. As Kong of Matthews Asia makes clear, more capital for the Chinese bond market would further the growth of China as an alternative pole of economic power to the U.S. and EU: Because China's savings is still greater than its investments, it enjoys a current account surplus and is not reliant on foreign capital inflows. In fact, China is already the single largest national / supranational creditor, bigger than the World Bank and the IMF. We believe developing a more liquid bond market with increasing foreign participations can solidify China's importance as a global creditor, providing pathway for more loans to be denominated in the Chinese renminbi to minimize asset liability mismatches. From a long-term perspective, this is just another milestone on the renminbi's path to potentially becoming a third reserve currency along with the U.S. dollar and the Euro.

Needless to say, the future of the U.S.-China relationship is shrouded in political uncertainty at present. A President Biden would certainly adopt different tactics in their deepening dispute, while President Trump's policy moves remain as unpredictable as ever. While it is reasonable to bet that in the long term the Chinese currency will achieve something like reserve status, it is also reasonable to bet that it will only get there after some reverses and drama along the way. And the old reasons to balk at entrusting capital to China haven't gone away. No other nation has managed growth on this scale in the last few decades without suffering some major crises along the way. The combination of state-command economics with capitalism looks as ungainly as ever, and the way it is currently being resolved, in favor of the state, isn't healthy for investors. But we live in the world as it is, and the alternatives are finite. When the main alternatives are the U.S. and the EU, with all their desperate monetary measures, China grows more appealing. Survival Tips Just one suggestion for the weekend, as the days shorten in the northern hemisphere and we still spend too much time streaming video. So I'd like to recommend My Octopus Teacher, which is now on Netflix. It tells the story of a South African who recovered from a mid-life crisis by forming a year-long relationship with a wild octopus. To do this, he learned to dive in freezing water in the kelp forests not far from the Cape of Good Hope, without a wetsuit or oxygen. And it's a documentary. It's a remarkable film. For an hour and a half you don't think about politics, or markets. It's great. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment